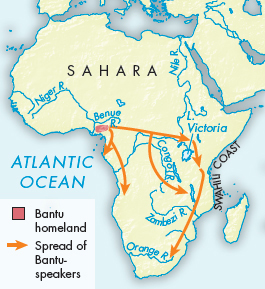

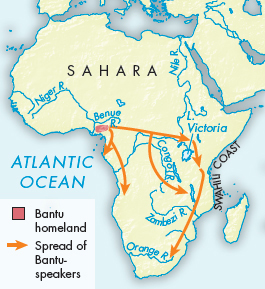

Bantu Migrations

The spread of ironworking is linked to the migrations of Bantu-speaking peoples. Today the overwhelming majority of the 70 million people living south of the Congo River speak a Bantu language. Lacking written sources, modern scholars have tried to reconstruct the history of Bantu-speakers on the basis of linguistics, oral traditions, archaeology, and anthropology. Botanists and zoologists have played particularly critical roles in providing information about early diets and environments.

Bantu-speaking peoples originated in the Benue region, the borderlands of modern Cameroon and Nigeria. In the second millennium B.C.E. they began to spread south and east into the equatorial forest zone. Historians still debate why they began this movement. Some hold that rapid population growth sent people in search of land. Others believe that the evolution of centralized kingdoms allowed rulers to expand their authority, while causing newly subjugated peoples to flee in the hope of regaining their independence.

Bantu Migrations, ca. 1000 B.C.E.–1500 C.E.

During the next fifteen hundred years, Bantu-speakers migrated throughout the savanna, adopted mixed agriculture, and learned ironworking. Mixed agriculture (cultivating cereals and raising livestock) and ironworking were practiced in western East Africa (the region of modern Burundi) in the first century B.C.E. In the first millennium C.E. Bantu-speakers migrated into eastern and southern Africa. Here the Bantu-speakers, with their iron weapons, either killed, drove off, or assimilated the hunting-gathering peoples they met. Some of the assimilated inhabitants gradually adopted a Bantu language, contributing to the spread of Bantu culture.

The settled cultivation of cereals, the keeping of livestock, and the introduction of new crops such as the banana — together with Bantu-speakers’ intermarriage with indigenous peoples — led over a long period to considerable population increases and the need to migrate farther. The so-called Bantu migrations should not be seen as a single movement sweeping across Africa from west to east to south and displacing all peoples in its path. Rather, those migrations were an extended series of group interactions between Bantu-speakers and pre-existing peoples in which bits of culture, languages, economies, and technologies were shared and exchanged to produce a wide range of cultural variation across central and southern Africa.1

The Bantu-speakers’ expansion and subsequent land settlement that dominated eastern and southern African history in the first fifteen hundred years of the Common Era were uneven. Significant environmental differences determined settlement patterns. Some regions had plenty of water, while others were very arid. These differences resulted in very uneven population distribution. The greatest population density seems to have been in the region bounded on the west by the Congo River and on the north, south, and east by Lakes Edward and Victoria and Mount Kilimanjaro. The rapid growth of the Bantu-speaking population led to further migration southward and eastward. By the eighth century the Bantu-speaking people had crossed the Zambezi River and had begun settling in the region of present-day Zimbabwe. By the fifteenth century they had reached Africa’s southeastern coast.