Maya Science and Religion

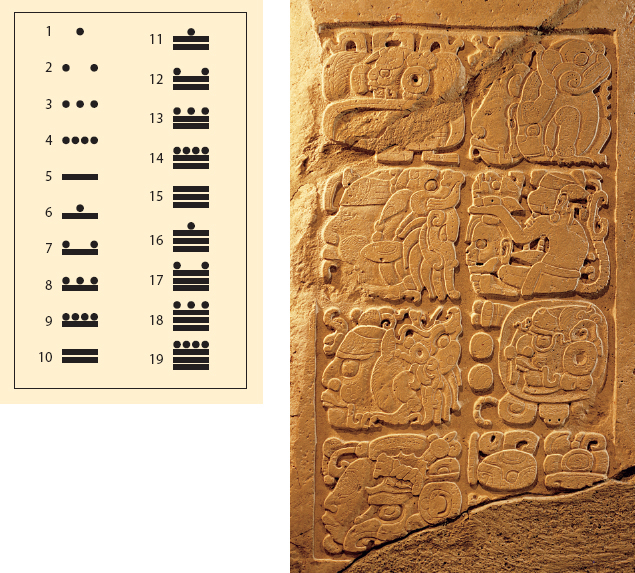

The Maya developed the most complex writing system in the Americas, a script with nearly a thousand glyphs. They recorded important events and observations in books made of bark paper and deerskin, on pottery, on stone pillars called steles, and on temples and other buildings. Archaeologists and anthropologists have demonstrated that the inscriptions are historical documents that record major events in the lives of Maya kings and nobles.

Surviving Maya books offer a window into religious rituals and practices, as well as Maya astronomy. From observation of the earth’s movements around the sun, the Maya used a calendar of eighteen 20-

The Maya devised a form of mathematics based on the vigesimal (20) rather than the decimal (10) system. More unusual was their use of the number zero, which allows for more complex calculations than are possible in number systems without it. The Maya’s proficiency with numbers made them masters of abstract knowledge — notably in astronomy and mathematics.

Between the eighth and tenth centuries the Maya abandoned their cultural and ceremonial centers. Archaeologists attribute their decline to a combination of agricultural failures due to drought, land exhaustion, overpopulation, disease, and constant wars fought for economic and political gain. Royalty also suffered from the decline in Maya civilization. When military, economic, and social conditions deteriorated, their subjects saw the kings as the cause and turned against them.

Decline did not mean disappearance. The Maya ceased building monumental architecture around 900 C.E., which likely marked the end of the era of rule by powerful kings who could mobilize the labor required to build it. The Maya persisted in farming communities, a pattern of settlement that helped preserve their culture and language in the face of external pressures. They resisted invasions from warring Aztec armies by dispersing from their towns and villages and residing in their milpas during invasions. When Aztec armies entered the Yucatán, communities dispersed, leaving Aztec armies with nothing to conquer. This tactic continued to serve the Maya under Spanish colonial rule, with many communities avoiding Spanish domination for generations.