Trade and Social Change

The most important development in West Africa before the European conquest was the decline of the Atlantic slave trade and the simultaneous rise in exports of palm oil and other commodities. This shift in African foreign trade marked the beginning of modern economic development in sub-

Although the trade in enslaved Africans was a global phenomenon, the transatlantic slave trade between Africa and the Americas became the most extensive and significant portion of it (see “The Transatlantic Slave Trade” in Chapter 20). After 1775 a broad campaign to abolish slavery, in which British women played a critical role, developed in Britain and grew into one of the first peaceful mass political movements based on the mobilization of public opinion in British history. Abolitionists also argued for a transition to legitimate (nonslave) trade, to end both the transatlantic slave trade and the internal African slave systems. In 1807 Parliament declared the slave trade illegal. Britain then established the antislavery West Africa Squadron, using its navy to seize slave runners’ ships, liberate the captives, and settle them in the British port of Freetown, in Sierra Leone, as well as in Liberia (see Map 25.1). Freed American slaves had established the colony of Liberia in 1821–

British action had a limited impact at first. Britain’s West Africa Squadron intercepted fewer than 10 percent of all slave ships, and the demand for slaves remained high on the expanding and labor-

As more nations joined Britain in outlawing the slave trade, shipments of human cargo slackened along the West African coast (see Map 25.1). At the same time the ancient but limited shipment of slaves across the Sahara and from the East African coast into the Indian Ocean and through the Red Sea expanded dramatically. Only in the 1860s did this trade begin to decline rapidly. As a result of these shifting currents, total slave exports from all regions of sub-

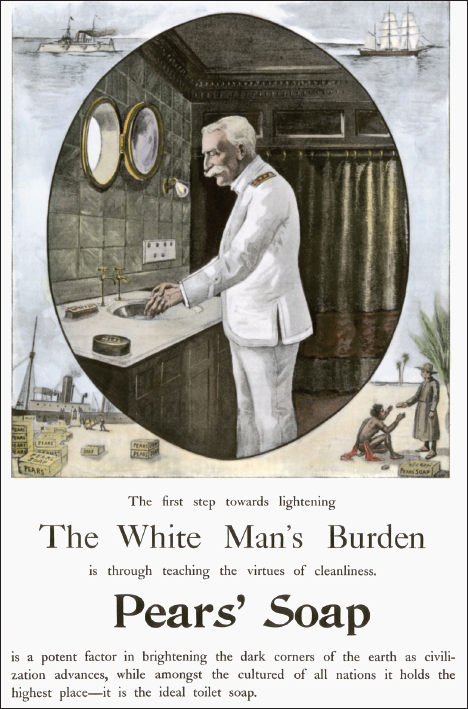

Nevertheless, beginning in West Africa, trade in tropical products did make steady progress for several reasons. First, with Britain encouraging palm tree cultivation as an alternative to the slave trade, palm oil sales from West Africa to Britain surged. Second, the sale of palm oil admirably served the self-

Finally, powerful West African rulers and warlords who had benefited from the Atlantic slave trade redirected some of their slaves’ labor into the production of legitimate goods for world markets. This was possible because local warfare and slave raiding continued to enslave large numbers of people in sub-

All the while, a new group of African merchants was emerging to handle legitimate trade, and some grew rich. Women were among the most successful of these merchants. There is a long tradition of West African women being actively involved in trade (see “Impact on African Societies” in Chapter 20), but the arrival of Europeans provided new opportunities. The African wife of a European trader served as her husband’s interpreter and learned all aspects of his business. If the husband died, the African wife inherited his commercial interests, including his inventory and his European connections. Many such widows used their considerable business acumen to make small fortunes.

By the 1850s and 1860s legitimate African traders, flanked by Western-