The Scramble for Africa, 1880–1914

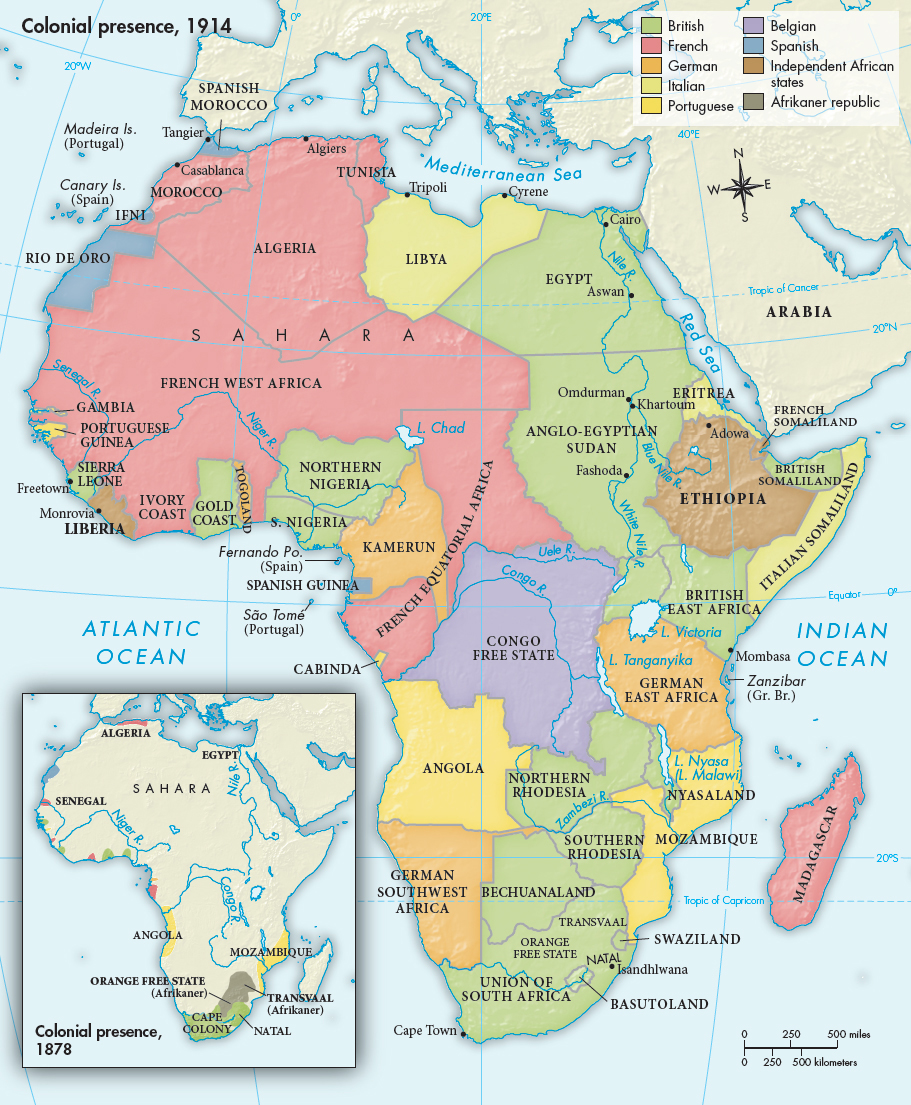

Between 1880 and 1914 Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, Spain, and Italy scrambled for African possessions as if their national livelihoods were at stake. In 1880 Europeans controlled barely 20 percent of the African continent, mainly along the coast; by 1914 they controlled over 90 percent. Only Ethiopia in northeast Africa and Liberia on the West African coast remained independent (Map 25.1).

In addition to the general causes underlying Europe’s imperialist burst after 1880, certain events and individuals stand out. First, as the antislavery movement succeeded in shutting down the Atlantic slave trade by the late 1860s, slavery’s persistence elsewhere attracted growing attention in western Europe and the Americas. Missionaries played a key role in publicizing the horrors of slave raids and the suffering of thousands of enslaved Africans. The public was led to believe that European conquest and colonization would end this human tragedy by bringing, in Scottish missionary David Livingstone’s famous phrase, “Commerce, Christianity, and Civilization” to Africa.

King Leopold II (r. 1865–

In addition to developing rules for imperialist competition, participants at the Berlin Conference also promised to stop black and Islamic slave dealers and to bring Christianity and civilization to Africa. In truth, however, these ideals ran a distant second to, and were not allowed to interfere with, the nations’ primary goal of commerce — holding on to their old markets and exploiting new ones.

The Berlin Conference coincided with Germany’s emergence as an imperial power. In 1884 and 1885 Bismarck’s Germany established protectorates over a number of small African kingdoms and societies (see Map 25.1). In acquiring colonies, Bismarck cooperated with France’s Jules Ferry against the British. The French expanded into West Africa and also formed a protectorate on the Congo River. Meanwhile, the British began enlarging their West African enclaves and pushed northward from the Cape Colony and westward from the East African coast.

The British also moved southward from Egypt, which they had seized in 1882 (see “Egypt: From Reform to British Occupation”), but were blocked in the eastern Sudan by fiercely independent Muslims. In 1881 a pious Sudanese leader, Muhammad Ahmad (1844–

All European nations resorted to some violence in their colonies to retain control, subdue the population, appropriate land, and force African laborers to work long hours at physically demanding, and often dangerous, jobs. In no colony, however, was the violence and brutality worse than in Leopold II’s Congo Free State. The European companies operating in the Congo Free State introduced slavery, unimaginable savagery, and terror.

Profits in the Congo Free State came first from the ivory trade, but in the 1890s, after many of the Congo’s elephant herds had been decimated, rubber surpassed ivory as the colony’s major income producer. Violence and brutality increased exponentially as industrial demand for rubber increased. Europeans and their well-