Individuals in Society: José Rizal

In the mid-

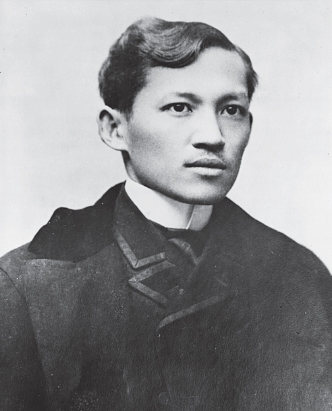

Mercado’s direct patrilineal descendant, José Rizal (1861–

While in Europe, Rizal became involved with Filipino revolutionaries and contributed numerous articles to their newspaper, La Solidaridad, published in Barcelona. Rizal advocated making the Philippines a province of Spain, giving it representation in the Spanish parliament, replacing Spanish friars with Filipino priests, and making Filipinos and Spaniards equal before the law. He spent a year at the British Museum doing research on the early phase of the Spanish colonization of the Philippines. He also wrote two novels.

The first novel, written in Spanish, was fired by the passions of nationalism. In satirical fashion, it depicts a young Filipino of mixed blood who studies for several years in Europe before returning to the Philippines to start a modern secular school in his hometown and to marry his childhood sweetheart. The church stands in the way of his efforts, and the colonial administration proves incompetent. The novel ends with the hero being gunned down after the friars falsely implicate him in a revolutionary conspiracy. Rizal’s own life ended up following this narrative surprisingly closely.

In 1892 Rizal left Europe, stopped briefly in Hong Kong, and then returned to Manila to help his family with a lawsuit. Though he secured his relatives’ release from jail, he ran into trouble himself. Because his writings were critical of the power of the church, he made many enemies, some of whom had him arrested. He was sent into exile to a Jesuit mission town on the relatively primitive island of Mindanao. There he founded a school and a hospital, and the Jesuits tried to win him back to the church. He kept busy during his four years in exile, not only teaching English, science, and self-

Tried for sedition by the military, Rizal was found guilty. When handed his death certificate, Rizal struck out the words “Chinese half-

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- How did Rizal’s comfortable family background contribute to his becoming a revolutionary?

- How would Rizal’s European contemporaries have reacted to his opposition to the Catholic Church?

DOCUMENT PROJECT

How did Filipinos and Americans respond to Spanish and American imperialism? Examine documents about the Philippines during the Spanish-