Immigration to the United States

After the Civil War ended in 1865, the United States underwent an industrial boom powered by exploitation of the country’s natural resources. The federal government turned over vast amounts of land and mineral resources to private industrialists for development. In particular, railroad companies — the foundation of industrial expansion — received 130 million acres. By 1900 the U.S. railroad system, was 193,000 miles long, connected every part of the nation, and represented 40 percent of the railroad mileage in the world, and it was all built by immigrant labor.

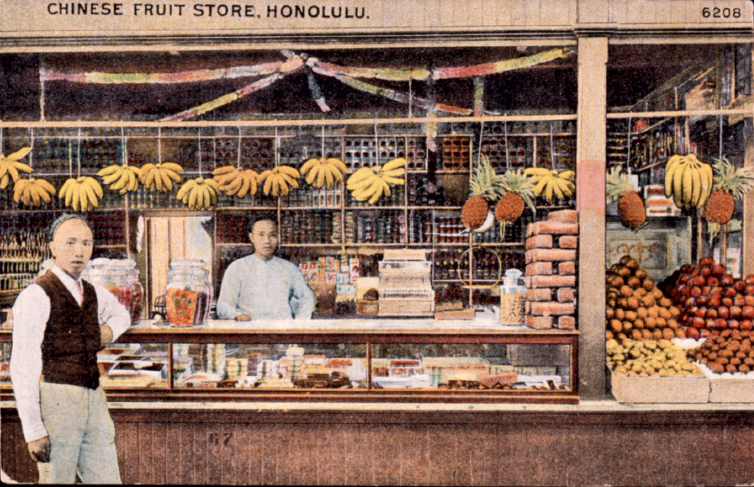

Between 1860 and 1914, 28 million immigrants came to the United States. Though many became rural homesteaders, industrial America developed on the sweat and brawn of immigrants. As in South America, immigration fed the growth of cities.

Working conditions for new immigrants were often deplorable. Industrialization had created a vast class of workers who depended entirely on wage labor. Employers paid women and children much less than men. Because business owners resisted government efforts to install costly safety devices, working conditions in mines and mills were frightful. In 1913 alone, even after some safety measures had been instituted, twenty-

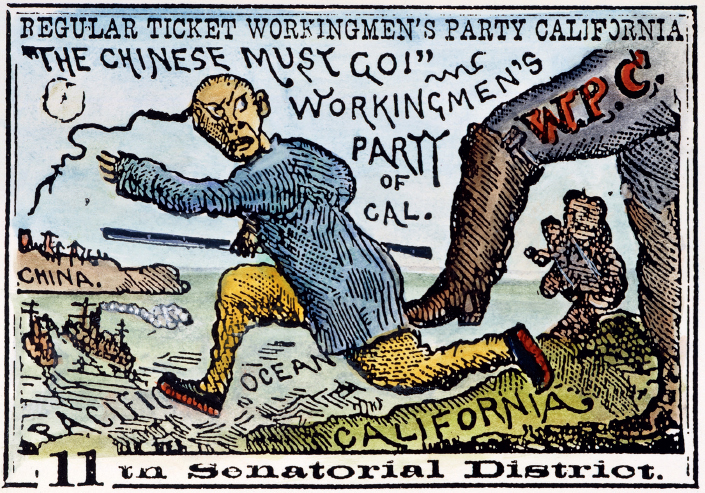

Immigrants faced more than economic exploitation: they were also subjected to harsh ethnic stereotypes and faced pressure to assimilate culturally. An economic depression in the 1890s increased resentment toward immigrants. Powerful owners of mines, mills, and factories fought the organization of labor unions, fired thousands of workers, slashed wages, and ruthlessly exploited their workers. Workers in turn feared that immigrant labor would drive salaries lower. Some of this antagonism sprang from racism, some from old Protestant suspicions of Roman Catholicism, the faith of many of the new arrivals. Long-

Immigrants were received very differently in Latin America, where oligarchs encouraged immigration from Europe, the Middle East, and Japan because they believed these “whiter” workers were superior to native-