Individuals in Society: Hatshepsut and Nefertiti

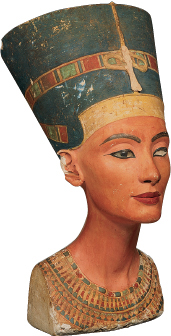

Painted limestone bust of Nefertiti. (bpk, Berlin/Aegyptisches Museum, Staaliche Museen, Berlin, Germany/Photo: Margarete Buesing/Art Resource, NY)

Egyptians understood the pharaoh to be the living embodiment of the god Horus, the source of law and morality, and the mediator between gods and humans. His connection with the divine stretched to members of his family, so his siblings and children were also viewed as in some ways divine. Because of this, a pharaoh often took his sister or half-sister as one of his wives. This concentrated divine blood set the pharaonic family apart from other Egyptians (who did not marry close relatives) and allowed the pharaohs to imitate the gods, who in Egyptian mythology often married their siblings. A pharaoh chose one of his wives to be the “Great Royal Wife,” or principal queen. Often this was a relative, though sometimes it was one of the foreign princesses who married pharaohs to establish political alliances.

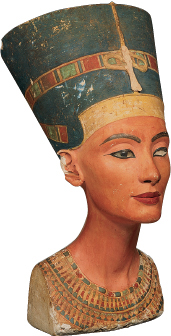

Granite head of Hatshepsut. (bpk, Berlin/Aegyptisches Museum, Staaliche Museen, Berlin, Germany/Photo: Margarete Buesing/Art Resource, NY)

The familial connection with the divine allowed a handful of women to rule in their own right in Egypt’s long history. We know the names of four female pharaohs, of whom the most famous was Hatshepsut. She was the sister and wife of Thutmose II and, after he died, served as regent — as adviser and co-ruler — for her young stepson Thutmose III, who was the son of another woman. Hatshepsut sent trading expeditions and sponsored artists and architects, ushering in a period of artistic creativity and economic prosperity. She built one of the world’s great buildings, an elaborate terraced temple at Deir el Bahri, which eventually served as her tomb. Hatshepsut’s status as a powerful female ruler was difficult for Egyptians to conceptualize, and she is often depicted in male dress or with a false beard, thus looking more like the male rulers who were the norm. After her death, Thutmose III tried to destroy all evidence that she had ever ruled, smashing statues and scratching her name off inscriptions, perhaps because of personal animosity and perhaps because he wanted to erase the fact that a woman had once been pharaoh. Only within recent decades have historians and archaeologists begun to (literally) piece together her story.

Though female pharaohs were very rare, many royal women had power through their position as Great Royal Wives. The most famous was Nefertiti (ca. 1370–1330 B.C.E.), the wife of Akhenaten. Her name means “the perfect (or beautiful) woman has come,” and inscriptions give her many other titles.

Nefertiti used her position to spread the new religion of the sun-god Aten. Together she and Akhenaten built a new palace at Akhetaten, the present-day Amarna, away from the old centers of power. There they developed the cult of Aten to the exclusion of the traditional deities. Nearly the only literary survivor of their religious belief is the “Hymn to Aten,” which declares Aten to be the only god. It describes Nefertiti as “the great royal consort whom he, Akhenaten, loves. The mistress of the Two Lands, Upper and Lower Egypt.”

Nefertiti is often shown as being the same size as her husband, and in some inscriptions she is performing religious rituals that would normally have been carried out only by the pharaoh. The exact details of her power are hard to determine, however. An older theory held that her husband removed her from power, though there is also speculation that she may have ruled secretly in her own right after his death. Her tomb has long since disappeared, though some scholars believe that an unidentified mummy discovered in 2003 in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings may be Nefertiti’s.

- Why might it have been difficult for Egyptians to accept a female ruler?

- What opportunities do hereditary monarchies such as that of ancient Egypt provide for women? How does this fit with gender hierarchies in which men are understood as superior?

Considering Egyptian views of gender roles, what complexities did Egyptian writers and artists face in depicting Hatshepsut? Analyze written and visual representations of Hatshepsut, and then complete a quiz and writing assignment based on the evidence and details from this chapter. See Document Project for Chapter 2