Urbanization

Cities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America expanded at an astonishing pace after 1945. Many doubled or even tripled in size in a single decade (Table 33.1). In 1950 there were only eight megacities (5 million or more inhabitants), and only two were in developing countries. Of the fifty-

| Area | 1925 | 1950 | 1975 | 2000 | 2025 (est.) |

| World Total | 21% | 28% | 39% | 50% | 63% |

| North America | 54 | 64 | 77 | 86 | 93 |

| Europe | 48 | 55 | 67 | 79 | 88 |

| Soviet Union | 18 | 39 | 61 | 76 | 87 |

| East Asia | 10 | 15 | 30 | 46 | 63 |

| Latin America | 25 | 41 | 60 | 74 | 85 |

| Africa | 8 | 13 | 24 | 37 | 54 |

|

Note: Little more than one- |

|||||

What caused this urban explosion? First, the overall population growth in the developing nations was critical. Urban residents gained substantially from a medical revolution that provided improved health care but only gradually began to reduce the size of their families. Second, more than half of all urban growth comes from rural migration. Manufacturing jobs in the developing nations were concentrated in cities.

Newcomers have streamed to the cities even when industrial jobs have been scarce, seeking any type of employment. Many migrants were pushed into cities. As large landowners found it more profitable to produce export crops, their increasingly mechanized operations reduced the need for agricultural laborers. Ethnic or political unrest in the countryside can also push migrants into cities. These push factors have been particularly strong in Latin America, with its neocolonial pattern of large landowners and foreign companies that exported food and raw materials.

Most of the exploding numbers of urban poor earned precarious livings in a bazaar economy comprised of petty traders and unskilled labor. In the bazaar economy, which echoed early preindustrial markets, regular salaried jobs were rare and highly prized, and a complex world of tiny, unregulated businesses and service occupations predominated. Peddlers and pushcart operators hawked their wares, and sweatshops and home-

After 1945 large-

For rural women, the consequences of male out-

Migration patterns in Latin America differed from this model. Whole families generally migrated, often to squatter settlements, much more commonly than in Asia and Africa. These families frequently belonged to the class of landless laborers, which was generally larger in Latin America than in Africa and Asia. Migration was also more likely to be permanent. Another difference was that single women were as likely as single men to move to the cities, in part because women were in high demand as domestic servants. Even so, in Latin America urban migration seems to have had less of an impact on family patterns and on women’s attitudes than it did in Asia and Africa.

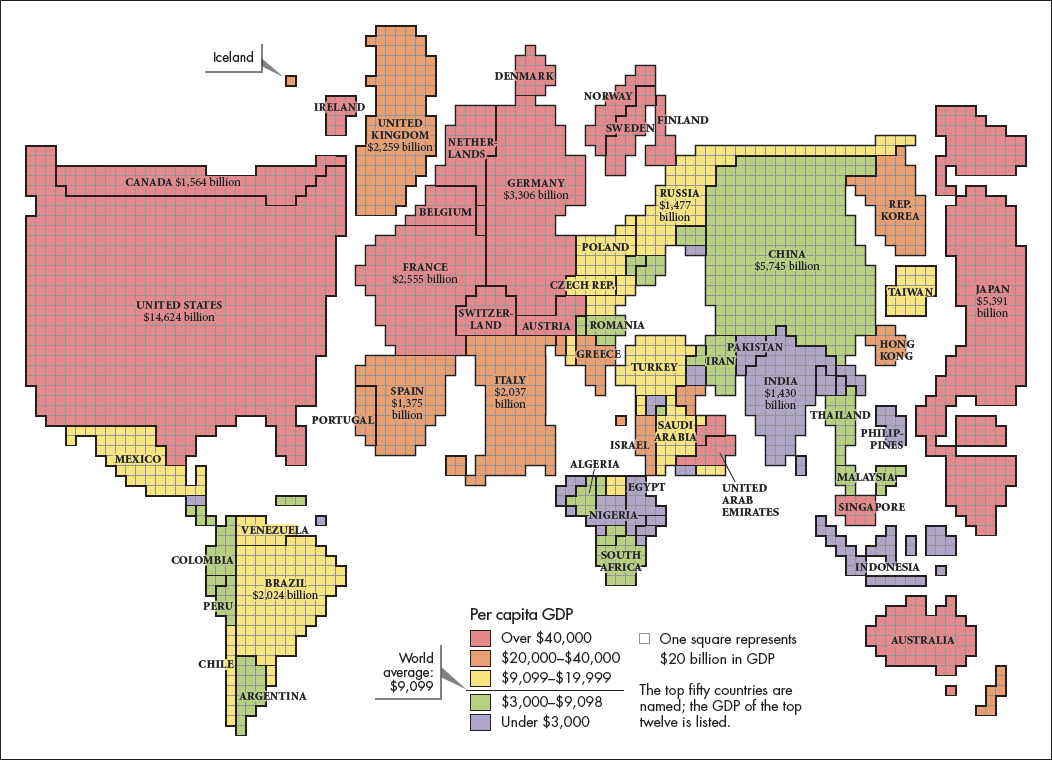

In cities the concentration of wealth in few hands has resulted in unequal consumption, education, health care, and employment. The gap between rich and poor around the world can be measured both between the city and the countryside, and within cities (Map 33.1). Wealthy city dwellers in developing countries often had more in common with each other than with their poorer urban and rural people in their own country. As a result, the elites have often favored globalization that connects them with wealthier nations.