Individuals in Society: The Ban Family

Ban Biao (3–

His twin brother, Ban Gu, was one of the most accomplished writers of his age, excelling in a distinctive literary form known as the rhapsody (fu). His “Rhapsody on the Two Capitals” is in the form of a dialogue between a guest from Chang’an and his host in Luoyang. It describes the palaces, spectacles, scenic spots, local products, and customs of the two great cities. Emperor Zhang (r. 76–

Ban Biao was working on the History of the Former Han Dynasty when he died in 54. Ban Gu took over this project, modeling it on Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian. He added treatises on law, geography, and bibliography, the last a classified list of books in the imperial library.

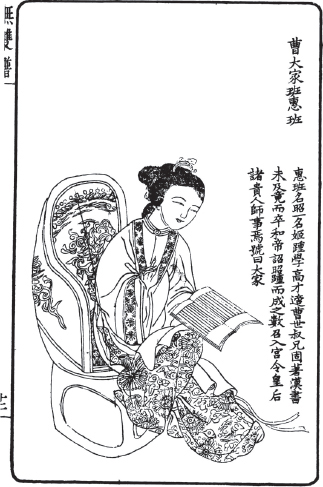

Because of his connection to a general out of favor, Ban Gu was sent to prison in 92, where he soon died. At that time the History of the Former Han Dynasty was still incomplete. The emperor called on Ban Gu’s widowed sister, Ban Zhao, to finish it. She came to the palace, where she not only worked on the history but also became a teacher of the women of the palace. According to the History of the Later Han, she taught them the classics, history, astronomy, and mathematics. In 106 an infant succeeded to the throne, and the widow of an earlier emperor became regent. This empress frequently turned to Ban Zhao for advice on government policies.

Ban Zhao credited her own education to her learned father and cultured mother and became an advocate of the education of girls. In her Admonitions for Women, Ban Zhao objected that many families taught their sons to read but not their daughters. She did not claim girls should have the same education as boys; after all, “just as yin and yang differ, men and women have different characteristics.” Women, she wrote, will do well if they cultivate womanly virtues such as humility. “Humility means yielding and acting respectful, putting others first and oneself last, never mentioning one’s own good deeds or denying one’s own faults, enduring insults and bearing with mistreatment, all with due trepidation.”* In subsequent centuries Ban Zhao’s Admonitions became one of the most commonly used texts for the education of Chinese girls.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- What inferences can you draw from the fact that a leading general had a brother who was a literary man?

- What does Ban Zhao’s life tell us about women in her society? How do you reconcile her personal accomplishments with the advice she gave for women’s education?

DOCUMENT PROJECT

What do Ban Zhao’s writings reveal about attitudes toward women during her time? Read sources by and about Ban Zhao, and then complete a quiz and writing assignment based on the evidence and details from this chapter. See Document Project for Chapter 7