Modern Publishing and the Book Industry

Throughout the nineteenth century, the rapid spread of knowledge and literacy as well as the Industrial Revolution spurred the emergence of the middle class. Its demand for books promoted the development of the publishing industry, which capitalized on increased literacy and widespread compulsory education. Many early publishers were mostly interested in finding quality authors and publishing books of importance. But with the growth of advertising and the rise of a market economy in the latter half of the nineteenth century, publishing gradually became more competitive and more concerned with sales.

The Formation of Publishing Houses

The modern book industry developed gradually in the nineteenth century with the formation of the early “prestigious” publishing houses: companies that tried to identify and produce the works of good writers.12 Among the oldest American houses established at the time (all are now part of major media conglomerates) were J. B. Lippincott (1792); Harper & Bros. (1817), which became Harper & Row in 1962 and HarperCollins in 1990; Houghton Mifflin (1832); Little, Brown (1837); G. P. Putnam (1838); Scribner’s (1842); E. P. Dutton (1852); Rand McNally (1856); and Macmillan (1869).

Between 1880 and 1920, as the center of social and economic life shifted from rural farm production to an industrialized urban culture, the demand for books grew. The book industry also helped assimilate European immigrants to the English language and American culture. In fact, 1910 marked a peak year in the number of new titles produced: 13,470, a record that would not be challenged until the 1950s. These changes marked the emergence of the next wave of publishing houses, as entrepreneurs began to better understand the marketing potential of books. These houses included Doubleday & McClure Company (1897), the McGraw-

Despite the growth of the industry in the early twentieth century, book publishing sputtered from 1910 into the 1950s, as profits were adversely affected by the two world wars and the Great Depression. Radio and magazines fared better because they were generally less expensive and could more immediately cover topical issues during times of crisis. But after World War II, the book publishing industry bounced back.

Types of Books

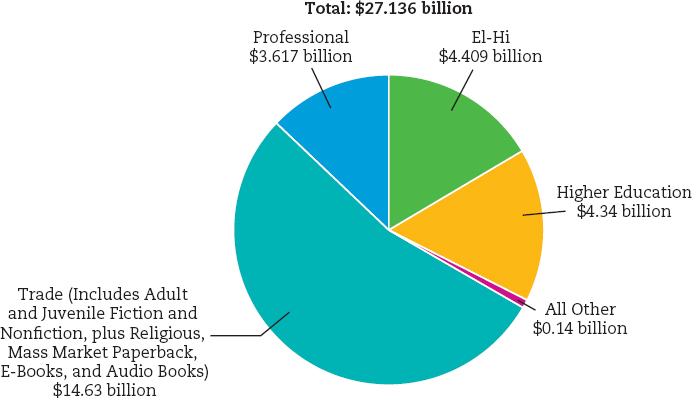

The divisions of the modern book industry come from economic and structural categories developed both by publishers and by trade organizations, such as the Association of American Publishers (AAP), the Book Industry Study Group (BISG), and the American Booksellers Association (ABA). The categories of book publishing that exist today include trade books (both adult and juvenile), professional books, elementary through high school (often called “el-

Trade Books

One of the most lucrative parts of the industry, trade books include hardbound and paperback books aimed at general readers and sold at commercial retail outlets. The industry distinguishes among adult trade, juvenile trade, and comics and graphic novels. Adult trade books include hardbound and paperback fiction; current nonfiction and biographies; literary classics; books on hobbies, art, and travel; popular science, technology, and computer publications; self-

Juvenile book categories range from preschool picture books to young-

Since 2003, the book industry has also been tracking sales of comics and graphic novels (long-

Professional Books

The counterpart to professional trade magazines, professional books target various occupational groups and are not intended for the general consumer market. This area of publishing capitalizes on the growth of professional specialization that has characterized the job market, particularly since the 1960s. Traditionally, the industry has subdivided professional books into the areas of law, business, medicine, and technical-

Textbooks

The most widely read secular book in U.S. history was The Eclectic Reader, an elementary-

In about half of the states, local school districts determine which el-

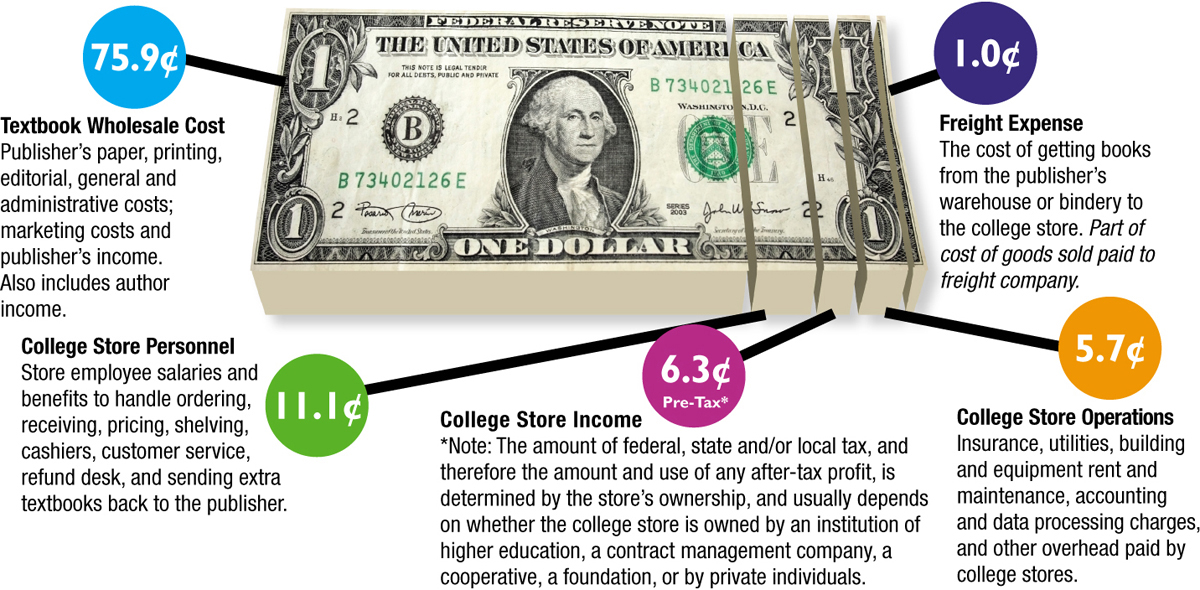

Unlike el-

As an alternative, some enterprising students have developed Web sites to trade, resell, and rent textbooks. Other students have turned to online purchasing, either through e-

Mass Market Paperbacks

Unlike the larger-

Paperbacks became popular in the 1870s, mostly with middle-

The popularity of paperbacks hit a major peak in 1939 with the establishment of Pocket Books by Robert de Graff. Revolutionizing the paperback industry, Pocket Books lowered the standard book price of fifty or seventy-

A major innovation of mass market paperback publishers was the instant book, a marketing strategy that involved publishing a topical book quickly after a major event occurred. Pocket Books produced the first instant book, Franklin Delano Roosevelt: A Memorial, six days after FDR’s death in 1945. Similar to made-

CASE STUDY

Comic Books: Alternative Themes, but Superheroes Prevail

by Mark C. Rogers

At the precarious edge of the book industry are comic books, which are sometimes called graphic novels or simply comix. Comics have long integrated print and visual culture, and they are perhaps the medium most open to independent producers—

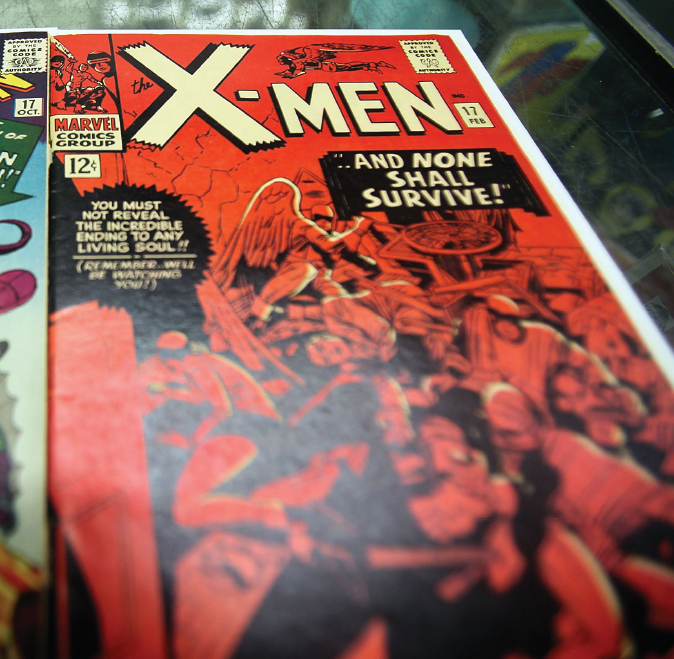

Comics are relatively young, first appearing in their present format in the 1920s in Japan and in the 1930s in the United States. They began as simple reprints of newspaper comic strips, but by the mid-

After World War II, comic books moved away from superheroes and began experimenting with other genres, most notably crime and horror (e.g., Tales from the Crypt). With the end of the war, the reading public was ready for more moral ambiguity than was possible in the simple good-

In the early 1950s, the popularity of crime and horror comics led to a moral panic about their effects on society. Fredric Wertham, a prominent psychiatrist, campaigned against them, claiming they led to juvenile delinquency. Wertham was joined by many religious and parent groups, and Senate hearings were held on the issue. In October 1954, the Comics Magazine Association of America adopted a code of acceptable conduct for publishers of comic books. One of the most restrictive examples of industry self-

The code had both immediate and long-

In the 1960s, Marvel and DC led the way as superhero comics regained their dominance. This period also gave rise to underground comics, which featured more explicit sexual, violent, and drug themes—

In the 1970s, responding in part to the challenge of the underground form, “legitimate” comics began to increase the political content and relevance of their story lines. In 1974, a new method of distributing comics—

The shift from newsstand to direct sales enabled comics to once again approach adult themes and also created an explosion in the number of comics available and in the number of companies publishing comics. Comic books peaked in 1993, generating more than $850 million in sales. That year, the industry sold about 45 million comic books per month, but it then began a steady decline that led Marvel to declare bankruptcy in the late 1990s. After comic-

Meanwhile, the two largest firms focus on the commercial synergies of particular characters or superheroes. DC, for example, is owned by Time Warner, which has used the DC characters, especially Superman and Batman, to build successful film and television properties through its Warner Brothers division. Marvel, which was bought by Disney in 2009, also got into the act with film versions of The Avengers made by their in-

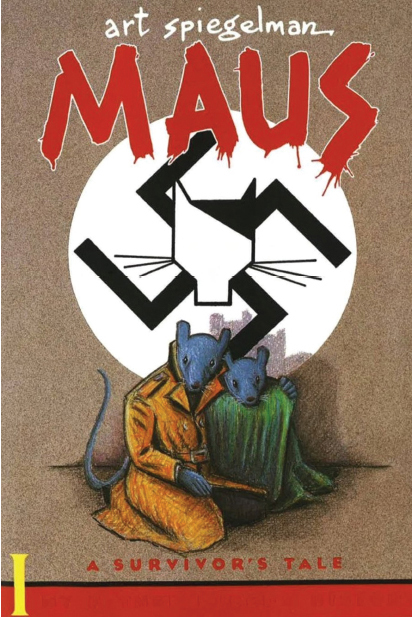

Comics, however, are again about more than just superheroes. In 1992, comics’ flexibility was demonstrated in Maus: A Survivor’s Tale by Art Spiegelman, cofounder and editor of Raw (an alternative magazine for comics and graphic art). The first comic-

Today, there are few divisions among traditional books and graphic novels. In 2012–

As other writers and artists continue to adapt the form to both fictional and nonfictional stories, comics endure as part of popular and alternative culture.

Mark C. Rogers teaches communication at Walsh University. He writes about television and the comic-

Religious Books

The best-

Throughout this period of change, the publication of fundamentalist and evangelical literature remained steady. It then expanded rapidly during the 1980s, when the Republican Party began making political overtures to conservative groups and prominent TV evangelists. After a record year in 2004 (twenty-

Reference Books

Another major division of the book industry—

The two most common reference books are encyclopedias and dictionaries. The idea of developing encyclopedic writings to document the extent of human knowledge is attributed to the Greek philosopher Aristotle. The Roman citizen Pliny the Elder (23–

The oldest English-

Dictionaries have also accounted for a large portion of reference sales. The earliest dictionaries were produced by ancient scholars attempting to document specialized and rare words. During the manuscript period in the Middle Ages, however, European scribes and monks began creating glossaries and dictionaries to help people understand Latin. In 1604, a British schoolmaster prepared the first English dictionary. In 1755, Samuel Johnson produced the Dictionary of the English Language. Describing rather than prescribing word usage, Johnson was among the first to understand that language changes—

University Press Books

The smallest division in the book industry is the nonprofit university press, which publishes scholarly works for small groups of readers interested in intellectually specialized areas, such as literary theory and criticism, history of art movements, contemporary philosophy, and the like. Professors often try to secure book contracts from reputable university presses to increase their chances for tenure, a lifetime teaching contract. Some university presses are very small, producing as few as ten titles a year. The largest—

University presses have not traditionally faced pressure to produce commercially viable books, preferring to encourage books about highly specialized topics by innovative thinkers. In fact, most university presses routinely lose money and are subsidized by their university. Even when they publish more commercially accessible titles, the lack of large marketing budgets prevents such books from reaching mass audiences. While large commercial trade houses are often criticized for publishing only blockbuster books, university presses often suffer the opposite criticism—