Trends and Issues in Book Publishing

LaunchPad

Based On: Making Books into Movies

Writers and producers discuss the process that brings a book to the big screen.

Discussion: How is the creative process of writing a novel different from making a movie? Which would you rather do, and why?

Ever since Harriet Beecher Stowe’s abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold fifteen thousand copies in fifteen days back in 1852 (and three million total copies prior to the Civil War), many American publishers have stalked the best-

Influences of Television and Film

There are two major facets in the relationship among books, television, and film: how TV can help sell books and how books serve as ideas for TV shows and movies. Through TV exposure, books by or about talk-

One of the most influential forces in promoting books on TV was Oprah Winfrey. Even before the development of Oprah’s Book Club in 1996, Oprah’s afternoon talk show had become a major power broker in selling books. In 1993, for example, Holocaust survivor and Nobel Prize recipient Elie Wiesel appeared on Oprah. Afterward, his 1960 memoir, Night, which had been issued as a Bantam paperback in 1982, returned to the best-

The film industry gets many of its story ideas from books (more than 1,450 feature-

Audio Books

Another major development in publishing has been the merger of sound recording with publishing. Audio books generally feature actors or authors reading entire works or abridged versions of popular fiction and nonfiction trade books. Indispensable to many sightless readers and older readers whose vision is diminished, audio books are also popular among regular readers who do a lot of commuter driving or who want to listen to a book at home while doing something else—

Convergence: Books in the Digital Age

In 1971, Michael Hart, a student computer operator at the University of Illinois, typed up the text of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, and thus the idea of the e-

Print Books Move Online

LaunchPad

Books in the New Millennium

Authors, editors, and bookstore owners discuss the future of book publishing.

Discussion: Are you optimistic or pessimistic about the future of books in an age of computers and e-

Early portable reading devices from RCA and Sony in the 1990s were criticized for being too heavy, too expensive, or too difficult to read, while their e-

Amazon has continued to refine its e-

By 2013, e-

The Future of E-

E-

Preserving and Digitizing Books

Another recent trend in the book industry involves the preservation of older books, especially those from the nineteenth century printed on acid-

Another way to preserve books is through digital imaging. The most extensive digitization project, Google Books, which began in 2004, features partnerships with the New York Public Library and about twenty major university research libraries—

GLOBAL VILLAGE

France and the Anti-

by Pamela Druckerman

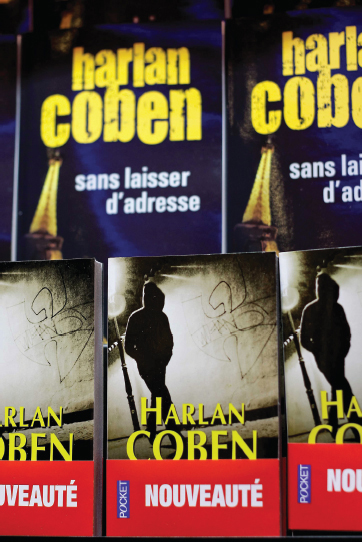

One of the maddening things about being a foreigner in France is that hardly anyone in the rest of the world knows what’s really happening here. They think Paris is a Socialist museum where people are exceptionally good at eating small bits of chocolate and tying scarves. In fact, the French have all kinds of worthwhile ideas on larger matters. This occurred to me recently when I was strolling through my museum-

I was in a bookstore-

France, meanwhile, has just unanimously passed a so-

The French secret is deeply un-

What underlies France’s book laws isn’t just an economic position—

Source: Excerpted from Pamela Druckerman, “The French Do Buy Books. Real Books.” New York Times, July 9, 2014, www.nytimes.com/

Media Literacy and the Critical Process

Banned Books and “Family Values”

In Free Speech for Me—

1 DESCRIPTION. Identify two contemporary books that have been challenged or banned in two separate communities. (Check the American Library Association Web site [www.ala.org/

2 ANALYSIS. What patterns emerge? What are the main arguments given for censoring the books? What are the main arguments of those defending these particular books? Are there any middle-

3 INTERPRETATION. Why did these issues arise? What do you think are the actual reasons why people would challenge or ban a book? (For example, can you tell if people seem genuinely concerned about protecting young readers or are just personally offended by particular books?) How do people handle book banning and issues raised by First Amendment protections of printed materials?

4 EVALUATION. Who do you think is right and wrong in these controversies? Why?

5 ENGAGEMENT. Read the two banned books. Then write a book review and publish it in a student or local paper, on a blog, or on Facebook. Through social media, link to the ALA’s list of banned books and challenge other people to read and review them.

Censorship and Banned Books

Over time, the wide circulation of books gave many ordinary people the same opportunities to learn that were once available to only a privileged few. However, as societies discovered the power associated with knowledge and the printed word, books were subjected to a variety of censors. Imposed by various rulers and groups intent on maintaining their authority, the censorship of books often prevented people from learning about the rituals and moral standards of other cultures. Political censors sought to banish “dangerous” books that promoted radical ideas or challenged conventional authority. In various parts of the world, some versions of the Bible, Karl Marx’s Das Kapital (1867), The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965), and Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses (1989) have all been banned at one time or another. In fact, one of the triumphs of the Internet is that it allows the digital passage of banned books into nations where printed versions have been outlawed. (For more on banned books, see “Media Literacy and the Critical Process: Banned Books and ‘Family Values’” on page 360.)

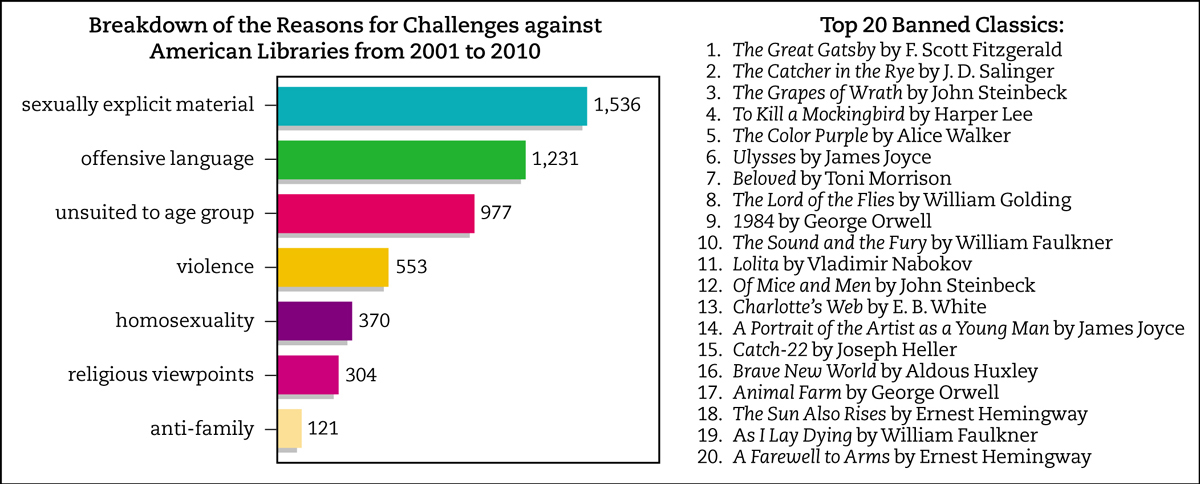

Each year, the American Library Association (ALA) compiles a list of the most challenged books in the United States. Unlike an enforced ban, a book challenge is a formal request to have a book removed from a public or school library’s collection. Common reasons for challenges include sexually explicit passages, offensive language, occult themes, violence, homosexual themes, promotion of a religious viewpoint, nudity, and racism. (The ALA defends the right of libraries to offer material with a wide range of views and does not support removing material on the basis of partisan or doctrinal disapproval.) Some of the most challenged books of the past decade include I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou, Forever by Judy Blume, the Harry Potter series by J. K. Rowling, and the Captain Underpants series by Dav Pilkey (see Figure 10.3).