Modern Journalism in the Information Age

In modern America, serious journalism has sought to provide information that enables citizens to make intelligent decisions. Today, this guiding principle faces serious threats. Why? First, we may just be producing too much information. According to social critic Neil Postman, as a result of developments in media technology, society has developed an “information glut” that transforms news and information into “a form of garbage.”5 Postman believed that scientists, technicians, managers, and journalists merely pile up mountains of new data, which add to the problems and anxieties of everyday life. As a result, too much unchecked data—

A second, related problem suggests that the amount of data the media now provide has questionable impact on improving public and political life. Many people feel cut off from our major institutions, including journalism. As a result, some citizens are looking to take part in public conversations and civic debates—

What Is News?

In a 1963 staff memo, NBC news president Reuven Frank outlined the narrative strategies integral to all news: “Every news story should . . . display the attributes of fiction, of drama. It should have structure and conflict, problem and denouement, rising and falling action, a beginning, a middle, and an end.”6 Despite Frank’s candid insights, many journalists today are uncomfortable thinking of themselves as storytellers. Instead, they tend to describe themselves mainly as information-

The major symbol of twentieth-

News is defined here as the process of gathering information and making narrative reports—

Characteristics of News

Over time, a set of conventional criteria for determining newsworthiness—information most worthy of transformation into news stories—

Most issues and events that journalists select as news are timely, or new. Reporters, for example, cover speeches, meetings, crimes, and court cases that have just happened. In addition, most of these events have to occur close by, or in proximity to, readers and viewers. Although local TV news and papers offer some national and international news, readers and viewers expect to find the bulk of news devoted to their own towns and communities.

Most news stories are narratives and thus contain a healthy dose of conflict—a key ingredient in narrative writing. In developing news narratives, reporters are encouraged to seek contentious quotes from those with opposing views. For example, stories on presidential elections almost always feature the most dramatic opposing Republican and Democratic positions. And many stories in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, pitted the values of other cultures against those of Western culture—

Reader and viewer surveys indicate that most people identify more closely with an individual than with an abstract issue. Therefore, the news media tend to report stories that feature prominent, powerful, or influential people. Because these individuals often play a role in shaping the rules and values of a community, journalists have traditionally been responsible for keeping a watchful eye on them and relying on them for quotes.

But reporters also look for human-

Two other criteria for newsworthiness are consequence and usefulness. Stories about isolated or bizarre crimes, even though they might be new, near, or notorious, often have little impact on our daily lives. To balance these kinds of stories, many editors and reporters believe that some news must also be of consequence to a majority of readers or viewers. For example, stories about issues or events that affect a family’s income or change a community’s laws have consequence. Likewise, many people look for stories with a practical use: hints on buying a used car or choosing a college, strategies for training a pet or removing a stain.

Finally, news is often about the novel and the deviant. When events happen that are outside the routine of daily life, such as a seven-

Values in American Journalism

Although newsworthiness criteria are a useful way to define news, they do not reveal much about the cultural aspects of news. News is both a product and a process. It is both the morning paper or evening newscast and a set of subtle values and shifting rituals that have been adapted to historical and social circumstances, such as the partisan press values of the eighteenth century or the informational standards of the twentieth century.

For example, in 1841, Horace Greeley described the newly founded New York Tribune as “a journal removed alike from servile partisanship on the one hand and from gagged, mincing neutrality on the other.”7 Greeley feared that too much neutrality would make reporters into wimps who stood for nothing. Yet the neutrality Greeley warned against is today a major value of conventional journalism, with mainstream reporters assuming they are acting as detached and all-

Neutrality Boosts Credibility—

As former journalism professor and reporter David Eason notes, “Reporters . . . have no special method for determining the truth of a situation nor a special language for reporting their findings. They make sense of events by telling stories about them.”8

Even though journalists transform events into stories, they generally believe that they are—

Like lawyers, therapists, and other professionals, many modern journalists believe that their credibility derives from personal detachment. Yet the roots of this view reside in less noble territory. Jon Katz, media critic and former CBS News producer, discusses the history of the neutral pose:

The idea of respectable detachment wasn’t conceived as a moral principle so much as a marketing device. Once newspapers began to mass market themselves in the mid-

To reach as many people as possible across a wide spectrum, publishers and editors realized as early as the 1840s that softening their partisanship might boost sales.

Partisanship Trumps Neutrality, Especially Online and on Cable

Since the rise of cable and the Internet, today’s media marketplace has offered a fragmented world where appealing to the widest audience no longer makes the best economic sense. More options than ever exist, with newspaper readers and TV viewers embracing cable news, social networks, blogs, and Twitter. The old “mass” audience has morphed into smaller niche audiences who embrace particular hobbies, story genres, politics, and social networks. News media outlets that hope to survive appeal no longer to mass audiences but to interest groups—

In such a marketplace, we see the decline of a more neutral journalistic model that promoted fact-

Other Cultural Values in Journalism

On September 17, 2011, a group of protesters gathered in Zuccotti Park in New York’s financial district and officially launched the Occupy Wall Street protest movement. Their slogan, “We are the 99 percent,” addressed the growing income disparity in the United States, furthering the idea that the nation’s wealth is unfairly concentrated among the top-

Even the neutral journalism model, which most reporters and editors still aspire to, remains a selective and uneven process. Reporters and editors turn some events into reports and discard many others. This process is governed by a deeper set of subjective beliefs that are not neutral. Sociologist Herbert Gans, who studied the newsroom cultures of CBS, NBC, Newsweek, and Time in the 1970s, generalized that several basic “enduring values” have been shared by most American reporters and editors. The most prominent of these values, which persist to this day, are ethnocentrism, responsible capitalism, small-

By ethnocentrism, Gans meant that in most news reporting, especially foreign coverage, reporters judge other countries and cultures on the basis of how “they live up to or imitate American practices and values.” Critics outside the United States, for instance, point out that CNN’s international news channels portray world events and cultures primarily from an American point of view rather than through some neutral, global lens.

Gans also identified responsible capitalism as an underlying value, contending that journalists sometimes naïvely assume that businesspeople compete with one another not primarily to maximize profits but “to create increased prosperity for all.” Gans pointed out that although most reporters and editors condemn monopolies, “there is little implicit or explicit criticism of the oligopolistic nature of much of today’s economy.”12 In fact, during the major economic recession of 2008–

Another value that Gans found was the romanticization of small-

Finally, individualism, according to Gans, remains the most prominent value underpinning daily journalism. Many idealistic reporters are attracted to this profession because it rewards the rugged tenacity needed to confront and expose corruption. Beyond this, individuals who overcome personal adversity are the subjects of many enterprising news stories.

Often, however, journalism that focuses on personal triumphs neglects to explain how large organizations and institutions work or fail. Many conventional reporters and editors are unwilling or unsure of how to tackle the problems raised by institutional decay. In addition, because they value their own individualism and are accustomed to working alone, many journalists dislike cooperating on team projects or participating in forums in which community members discuss their own interests and alternative definitions of news.13

Facts, Values, and Bias

Traditionally, reporters have aligned facts with an objective position and values with subjective feelings.14 Within this context, news reports offer readers and viewers details, data, and description. It then becomes the citizen’s responsibility to judge and take a stand about the social problems represented by the news. Given these assumptions, reporters are responsible only for adhering to the tradition of the trade—

Still, most public surveys have shown that while journalists may work hard to stay neutral, the addition of partisan cable channels such as Fox News and MSNBC has undermined reporters who try to report fairly. So while conservatives tend to see the media as liberally biased, liberals tend to see the media as favoring conservative positions (see “Case Study: Bias in the News” on page 484). But political bias is complicated. During the early years of Barack Obama’s presidency, many pundits on the political Right argued that Obama got much more favorable media coverage than did former president George W. Bush. But left-

According to Evan Thomas of Newsweek magazine, “the suspicion of press bias” comes from two assumptions or beliefs that the public holds about news media: “The first is that reporters are out to get their subjects. The second is that the press is too close to its subjects.”15 Thomas argues that the “press’s real bias is for conflict.” He says that mainstream editors and reporters traditionally value scandals, “preferably sexual,” and “have a weakness for war, the ultimate conflict.” Thomas claims that in the end, journalists “are looking for narratives that reveal something of character. It is the human drama that most compels our attention.”16

CASE STUDY

Bias in the News

All news is biased. News, after all, is primarily selective storytelling, not objective science. Editors choose certain events to cover and ignore others; reporters choose particular words or images to use and reject others. The news is also biased in favor of storytelling, drama, and conflict; in favor of telling “two sides of a story”; in favor of powerful and well-

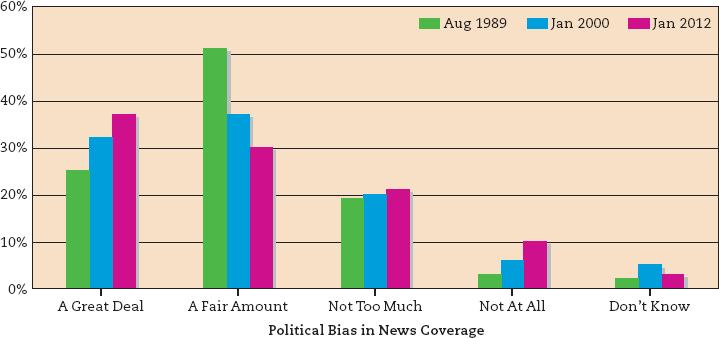

In terms of political bias, a 2012 Pew Research Center study reported that 37 percent of Americans see “a great deal of political bias” in the news—

Given primary dictionary definitions of liberal (adj., “favorable to progress or reform, as in political or religious affairs”) and conservative (adj., “disposed to preserve existing conditions, institutions, etc., or to restore traditional ones, and to limit change”), it is not surprising that a high percentage of liberals and moderates gravitate to mainstream journalism.2 A profession that honors documenting change, checking power, and reporting wrongdoing would attract fewer conservatives, who are predisposed to “limit change.” As sociologist Herbert Gans demonstrated in Deciding What’s News, most reporters are socialized into a set of work rituals—

Still, the “liberal bias” narrative persists. In 2001, Bernard Goldberg, a former producer at CBS News, wrote Bias. Using anecdotes from his days at CBS, he maintained that national news slanted to the Left.4 In 2003, Eric Alterman, a columnist for the Nation, countered with What Liberal Media? Alterman admitted that mainstream news media do reflect more liberal views on social issues but argued that they had become more conservative on politics and economics—

Since journalists are primarily storytellers, and not scientists, searching for liberal or conservative bias should not be the main focus of our criticism. Under time and space constraints, most journalists serve the routine practices of their profession, which call on them to moderate their own political agendas. News reports, then, are always “biased,” given human imperfection in storytelling and in communicating through the lens of language, images, and institutional values. Fully critiquing news stories must depend, then, on whether they are fair, represent an issue’s complexity, provide verification and documentation, represent multiple views, and serve democracy.

Data from: Pew Research Center Survey, January 5–

Note: Figures may not add up to 100 percent because of rounding.