Ethics and the News Media

National journalists occasionally face a profound ethical dilemma, especially in the aftermath of 9/11: When is it right to protect government secrets, and when should those secrets be revealed to the public? How must editors weigh such decisions when national security bumps up against citizens’ need for information?

In 2006, Dean Baquet, then editor of the Los Angeles Times (in 2014, he became the executive editor of the New York Times), and Bill Keller, then executive editor of the New York Times, wrestled with these questions in a coauthored editorial:

Finally, we weigh the merits of publishing against the risks of publishing. There is no magic formula. . . . We make our best judgment.

When we come down on the side of publishing, of course, everyone hears about it. Few people are aware when we decide to hold an article. But each of us, in the past few years, has had the experience of withholding or delaying articles when the administration convinces us that the risk of publication outweighed the benefits. . . .

We understand that honorable people may disagree . . . to publish or not to publish. But making those decisions is a responsibility that falls to editors, a corollary to the great gift of our independence. It is not a responsibility we take lightly. And it is not one we can surrender to the government.17

What makes the predicament of these national editors so tricky is that in the war against terrorism, some politicians maintain that one value terrorists truly hate is “our freedom.” At the same time, some of these same politicians criticized the Times for carefully editing and then publishing the WikiLeaks documents. There is irony here: What is more integral to liberty than the freedom of an independent press—

Ethical Predicaments

What is the moral and social responsibility of journalists, not only for the stories they report but also for the actual events or issues they are shaping for millions of people? Wrestling with such media ethics involves determining the moral response to a situation through critical reasoning. Although national security issues raise problems for a few of our largest news organizations, the most frequent ethical dilemmas encountered in most newsrooms across the United States involve intentional deception, privacy invasions, and conflicts of interest.

Deploying Deception

Ever since Nellie Bly faked insanity to get inside an asylum in the 1880s, investigative journalists have used deception to get stories. Today, journalists continue to use disguises and assume false identities to gather information on social transgressions. Beyond legal considerations, though, a key ethical question comes into play: Does the end justify the means? For example, can a newspaper or TV newsmagazine use deceptive ploys to go undercover and expose a suspected fraudulent clinic that promises miracle cures at a high cost? Are news professionals justified in posing as clients desperate for a cure?

In terms of ethics, there are at least two major positions and multiple variations. At one end of the spectrum, absolutist ethics suggests that a moral society has laws and codes, including honesty, that everyone must live by. This means citizens, including members of the news media, should tell the truth at all times and in all cases. In other words, the ends (exposing a phony clinic) never justify the means (using deception to get the story). An editor who is an absolutist would cover this story by asking a reporter to find victims who have been ripped off by the clinic and then telling the story through their eyes. At the other end of the spectrum is situational ethics, which promotes ethical decisions on a case-

Should a journalist withhold information about his or her professional identity to get a quote or a story from an interview subject? Many sources and witnesses are reluctant to talk with journalists, especially about a sensitive subject that might jeopardize a job or hurt another person’s reputation. Journalists know they can sometimes obtain information by posing as someone other than a journalist, such as a curious student or a concerned citizen.

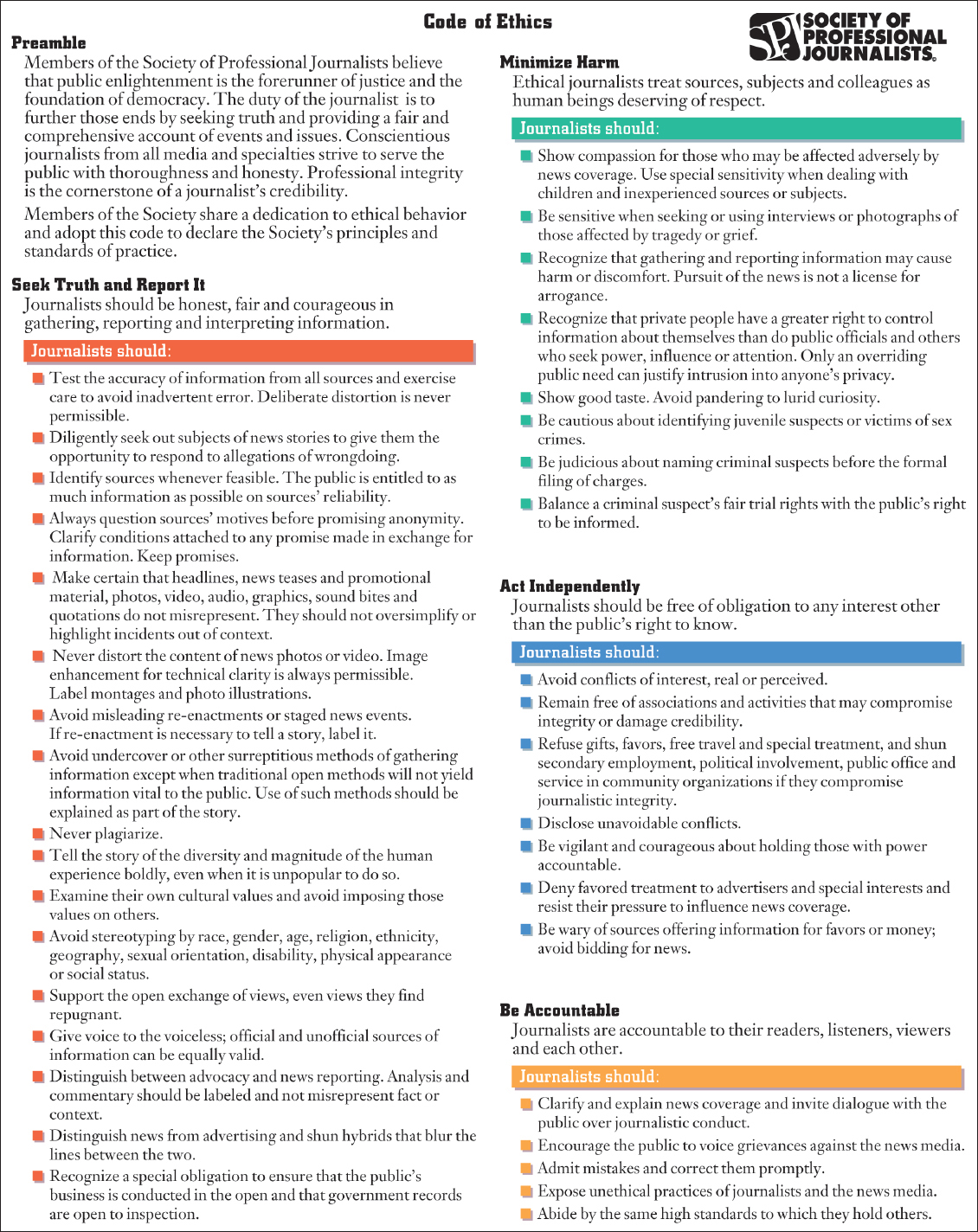

Most newsrooms frown on such deception. In particular situations, though, such a practice might be condoned if reporters and their editors believed that the public needed the information. The ethics code adopted by the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) is mostly silent on issues of deception. The code does say that “journalists should be honest, fair and courageous in gathering, reporting and interpreting information,” and it also calls on journalists to “seek truth and report it” (see Figure 14.1 on page 487). So is it being “honest” for reporters to use deceptive tactics in the pursuit of truth?

Invading Privacy

To achieve “the truth” or to “get the facts,” journalists routinely straddle a line between “the public’s right to know” and a person’s right to privacy. For example, journalists may be sent to hospitals to gather quotes from victims who have been injured. Often there is very little the public might gain from such information, but journalists worry that if they don’t get the quote, a competitor might. In these instances, have the news media responsibly weighed the protection of individual privacy against the public’s right to know? Although the latter is not constitutionally guaranteed, journalists invoke the public’s right to know as justification for many types of stories.

One infamous example is the recent phone hacking scandal involving News Corp.’s now-

In the case of privacy issues, media companies and journalists should always ask these ethical questions: What public good is being served here? What significant public knowledge will be gained through the exploitation of a tragic private moment? Although journalism’s code of ethics says, “The news media must guard against invading a person’s right to privacy,” this clashes with another part of the code: “The public’s right to know of events of public importance and interest is the overriding mission of the mass media.”18 When these two ethical standards collide, should journalists err on the side of the public’s right to know?

Conflict of Interest

Journalism’s code of ethics also warns reporters and editors not to place themselves in positions that produce a conflict of interest—that is, any situation in which journalists may stand to benefit personally from stories they produce. “Gifts, favors, free travel, special treatment or privileges,” the code states, “can compromise the integrity of journalists and their employers. Nothing of value should be accepted.”19 Although small newspapers with limited resources and poorly paid reporters might accept such “freebies” as game tickets for their sportswriters and free meals for their restaurant critics, this practice does increase the likelihood of a conflict of interest that produces favorable or uncritical coverage.

On a broader level, ethical guidelines at many news outlets attempt to protect journalists from compromising positions. For instance, in most cities, U.S. journalists do not actively participate in politics or support social causes. Some journalists will not reveal their political affiliations, and some even decline to vote.

For these journalists, the rationale behind their decision is straightforward: Journalists should not place themselves in a situation in which they might have to report on the misdeeds of an organization or a political party to which they belong. If a journalist has a tie to any group, and that group is later suspected of involvement in shady or criminal activity, the reporter’s ability to report on that group would be compromised—

In the digital age, conflict of interest cases surrounding opinion blogging have grown more complicated, especially when those opinion blogs run under the banner of traditional news media. For example, in 2010 David Weigel, whom the Washington Post hired to blog about the conservative movement, was forced to resign after private e-

Resolving Ethical Problems

When a journalist is criticized for ethical lapses or questionable reporting tactics, a typical response might be “I’m just doing my job” or “I was just getting the facts.” Such explanations are troubling, though, because in responding this way, reporters are transferring personal responsibility for the story to a set of institutional rituals.

There are, of course, ethical alternatives to self-

Aristotle, Kant, and Bentham and Mill

The Greek philosopher Aristotle offered an early ethical concept, the “golden mean”—a guideline for seeking balance between competing positions. For Aristotle, this was a desirable middle ground between extreme positions, usually with one regarded as deficient and the other as excessive. For example, Aristotle saw ambition as the balance between sloth and greed.

Another ethical principle entails the “categorical imperative” developed by German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–

British philosophers Jeremy Bentham (1748–

Developing Ethical Policy

Arriving at ethical decisions involves several steps. These include laying out the case; pinpointing the key issues; identifying involved parties, their intents, and their competing values; studying ethical models; presenting strategies and options; and formulating a decision.

One area that requires ethics is covering the private lives of people who have unintentionally become prominent in the news. Consider Richard Jewell, the Atlanta security guard who, for eighty-

At least two key ethical questions emerged: (1) Should the news media have named Jewell as a suspect even though he was never charged with a crime? (2) Should the media have camped out daily in front of his mother’s house in an attempt to interview him and his mother? The Jewell case pitted the media’s right to tell stories and earn profits against a person’s right to be left alone.

Working through the various ethical stages, journalists formulate policies grounded in overarching moral principles.22 Should reporters, for instance, follow the Golden Rule and be willing to treat themselves, their families, or their friends the way they treated the Jewells? Or should they invoke Aristotle’s “golden mean” and seek moral virtue between extreme positions?

In Richard Jewell’s situation, journalists could have developed guidelines to balance Jewell’s interests and the news media’s. For example, in addition to apologizing for using Jewell’s name in early accounts, reporters might have called off their stakeout and allowed Jewell to set interview times at a neutral site, where he could talk with a small pool of journalists designated to relay information to other media outlets.