Alternative Models: Public Journalism and “Fake” News

LaunchPad

Fake News/Real News: A Fine Line

The editor of the Onion describes how the publication critiques “real” news media.

Discussion: How many of your news sources might be considered “fake” news as opposed to traditional news, and how do you decide which sources to consult?

In 1990, Poland was experiencing growing pains as it shifted from a state-

These developments triggered heated discussions in the newsroom. A small group of young reporters, some of whom had recently worked in the United States, argued that the best way to cover the story was to describe the new crime wave and relay the facts to readers in a neutral manner. Another group, many of whom were older and more experienced, felt that the paper should take an advocacy stance and condemn the criminals through interpretive columns on the front page. The older guard won this particular debate, and more interpretive pieces appeared.40

This story illustrates the two competing models that have influenced American and European journalism since the early twentieth century. The first—

In most American newspapers today, the informational model dominates the front page, while the partisan model remains confined to the editorial pages and an occasional front-

The Public Journalism Movement

One way technology has allowed citizens to become involved in the reporting of news is through cell phone photos and videos uploaded online. Witnesses can now pass on what they have captured to major mainstream news sources, like CNN’s iReports, or post to their own blogs and Web sites. Victoria Sinistra/AFP/Getty Images

From the late 1980s through the 1990s, a number of papers experimented with ways to involve readers more actively in the news process. These experiments surfaced primarily at midsize daily papers, including the Charlotte Observer, the Wichita Eagle, the Virginian-

Public journalism is best imagined as a conversational model for news practice. Modern journalism had drawn a distinct line between reporter detachment and community involvement; public journalism—

In the 1990s—

CASE STUDY

A Lost Generation of Journalists?

The economic crisis in 2008–

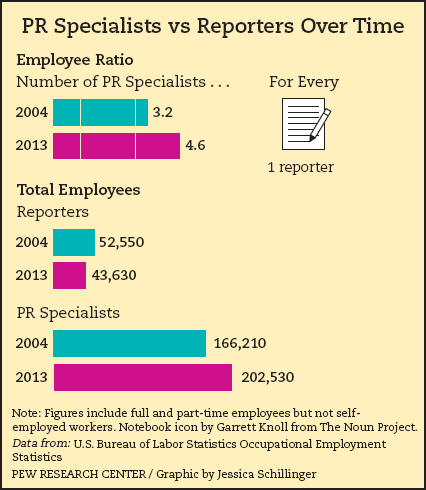

Back in the 1970s, the number of PR employees in the U.S. was roughly equal to the number of reporters working in print and broadcasting. That ratio became 2 to 1 by 2000, 3.2 to 1 by 2004, and was nearing 5 to 1 by 2013. Between 2004 and 2013, the number of reporters fell from 52,550 to 43,630, while the number of PR specialists “grew by 22 percent, from 166,210 to 202,530.”2

The pay differences were also striking, according to the Pew study. Over the past decade, the salary gap between PR and news workers had, by 2013, grown to almost $20,000 per year; PR specialists earned an average of $54,940 annually, while reporters averaged $35,600. Nine years earlier, the disparity was not quite as large: $43,830 for PR and $31,320 for reporters.3

The decline in reporters and the rise of PR and political spin doctors raises significant concerns. During and following the digital turn, journalists have increasingly relied on press releases both for story ideas and for news copy. However, according to Robert McChesney and John Nichols in The Death and Life of American Journalism, “as editorial staffs shrink, there is less ability for news media to interrogate and counter the claims in press releases.”4 As an example, a 2012 Pew study reported that during the national election that year, journalists “often functioned as megaphones for political partisans, relaying assertions rather than contextualizing them.”5

With the decrease in reporters and the increase in PR practitioners, far fewer journalists are available to vet information and fact-

Finally, the biggest concern may be the lost generation of journalists. More students coming from journalism schools are taking jobs as business writers and PR workers. The journalism profession, then, needs to not only figure out a new business model for the twenty-

An Early Public Journalism Project

Although isolated citizen projects and reader forums are sprinkled throughout the history of journalism, the public journalism movement began in earnest in 1987 in Columbus, Georgia. The city was suffering from a depressed economy, an alienated citizenry, and an entrenched leadership. In response, a team of reporters from the Columbus Ledger-

When the provocative series evoked little public response, the paper’s leadership realized there was no mechanism or forum for continuing the public discussions about the issues raised in the series. Consequently, the paper created such a forum by organizing a town meeting and helped create a new civic organization to tackle issues such as racial tension and teenage antisocial behavior.

The Columbus project generated public discussion, involved more people in the news process, and eased race and class tensions by bringing various groups together in public conversations. In the newsroom, the Ledger-

Criticizing Public Journalism

By 2000, more than a hundred newspapers, many teamed with local television and public radio stations, had practiced some form of public journalism. Yet many critics remained skeptical of the experiment, raising a number of concerns, including the weakening of four journalistic hallmarks: editorial control, credibility, balance, and diverse views.43

First, some editors and reporters argued that public journalism had been co-

Second, critics worried that public journalism compromised the profession’s credibility, which many believe derives from detachment. They argued that public journalism turned reporters into participants rather than observers. However, as the Wichita Eagle’s editor Davis Merritt pointed out, professionals who have credibility “share some basic values about life, some common ground about common good.” Yet many journalists have insisted they “don’t share values with anyone; that [they] are value-

Third, critics also contended that public journalism undermined balance and the both-

Fourth, many traditional reporters asserted that public journalism, which they considered merely a marketing tool, had not addressed the changing economic structure of the news business—

“Fake” News and Satiric Journalism

For many young people, it is especially disturbing that two wealthy, established political parties—

Why shouldn’t people, then, be cynical about politics? It is this cynicism that has drawn increasingly larger audiences to “fake” news shows like The Daily Show, The Nightly Show, and Last Week Tonight. Following in the tradition of Saturday Night Live (SNL), which began in 1975, news satires tell their audiences something that seems truthful about politicians and how they try to manipulate media and public opinion. But most important, these shows use humor to critique the news media and our political system. SNL’s sketches on GOP vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin in 2008 drew large audiences and shaped the way younger viewers thought about the election.

The Colbert Report satirized cable news hosts, particularly Fox’s Bill O’Reilly and MSNBC’s Chris Matthews, and the bombastic opinion-

On The Daily Show, a cast of fake reporters are digitally superimposed in front of exotic foreign locales, Washington, D.C., or other U.S. locations. In a 2004 exchange with “political correspondent” Rob Corddry, host Jon Stewart asked him for his opinion about presidential campaign tactics. “My opinion? I don’t have opinions,” Corddry answered. “I’m a reporter, Jon. My job is to spend half the time repeating what one side says, and half the time repeating the other. Little thing called objectivity; might want to look it up.”

During his reign as news court jester, Stewart, who stepped down from The Daily Show in 2015, has exposed the melodrama of TV news that nightly depicts the world in various stages of disorder while offering the stalwart, comforting presence of celebrity-

Yet even as fake anchors, satirists like Stewart and Oliver display much greater range of emotion—

While fake news programs often mock the formulas that real TV news programs have long used, they also present an informative and insightful look at current events and the way “traditional” media cover them. For example, he exposes hypocrisy by juxtaposing what a politician said recently in the news with the opposite position articulated by the same politician months or years earlier. Indeed, many Americans have admitted that they watch satires such as The Daily Show not only to be entertained but also to stay current with what’s going on in the world. In fact, a prominent Pew Research Center study back in 2007 found that people who watched these satiric shows were more often “better informed” than most other news consumers, usually because these viewers tended to get their news from multiple sources and a cross section of news media.45

Although the world has changed, local TV news story formulas (except for splashy opening graphics and Doppler weather radar) have gone virtually unaltered since the 1970s, when SNL’s “Weekend Update” first started making fun of TV news. Newscasts still limit reporters’ stories to two minutes or less and promote stylish anchors, a “sports guy,” and a certified meteorologist as familiar personalities whom we invite into our homes each evening. Now that a generation of viewers has been raised on the TV satire and political cynicism of “Weekend Update,” David Letterman, Jimmy Fallon, Conan O’Brien, The Daily Show, and The Colbert Report, the slick, formulaic packaging of political ads and the canned, cautious sound bites offered in news packages are simply not as persuasive as they once were.

Journalism should break free from tired formulas—