Early Media Research Methods

Public opinion polls suggest that the American public’s attitude toward same-

In the early days of the United States, philosophical and historical writings tried to explain the nature of news and print media. For instance, the French political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville, author of Democracy in America, noted differences between French and American newspapers in the early 1830s:

In France the space allotted to commercial advertisements is very limited, and . . . the essential part of the journal is the discussion of the politics of the day. In America three quarters of the enormous sheet are filled with advertisements and the remainder is frequently occupied by political intelligence or trivial anecdotes; it is only from time to time that one finds a corner devoted to the passionate discussions like those which the journalists of France every day give to their readers.1

During most of the nineteenth century, media analysis was based on moral and political arguments, as demonstrated by the de Tocqueville quote.2

More scientific approaches to mass media research did not begin to develop until the late 1920s and 1930s. In 1920, Walter Lippmann’s Liberty and the News called on journalists to operate more like scientific researchers in gathering and analyzing factual material. Lippmann’s next book, Public Opinion (1922), was the first to apply the principles of psychology to journalism. Described by media historian James Carey as “the founding book in American media studies,”3 it led to an expanded understanding of the effects of the media, emphasizing data collection and numerical measurement. According to media historian Daniel Czitrom, by the 1930s “an aggressively empirical spirit, stressing new and increasingly sophisticated research techniques, characterized the study of modern communication in America.”4 Czitrom traces four trends between 1930 and 1960 that contributed to the rise of modern media research: propaganda analysis, public opinion research, social psychology studies, and marketing research.

Propaganda Analysis

After World War I, some media researchers began studying how governments used propaganda to advance the war effort. They found that during the war, governments routinely relied on propaganda divisions to spread “information” to the public. According to Czitrom, though propaganda was considered a positive force for mobilizing public opinion during the war, researchers after the war labeled propaganda negatively, calling it “partisan appeal based on half-

Public Opinion Research

Researchers soon went beyond the study of war propaganda and began to focus on more general concerns about how the mass media filtered information and shaped public attitudes. In the face of growing media influence, Walter Lippmann distrusted the public’s ability to function as knowledgeable citizens as well as journalism’s ability to help the public separate truth from lies. In promoting the place of the expert in modern life, Lippmann celebrated the social scientist as part of a new expert class that could best make “unseen facts intelligible to those who have to make decisions.”7

Today, social scientists conduct public opinion research, or citizen surveys; these have become especially influential during political elections. On the upside, public opinion research on diverse populations has provided insights into citizen behavior and social differences, especially during election periods or following major national events. For example, a 2013 Washington Post–ABC News poll confirmed what several other reputable polls reported: A majority of Americans support same-

On the downside, journalism has become increasingly dependent on polls, particularly for political insight. Some critics argue that this heavy reliance on measured public opinion has begun to adversely affect the active political involvement of American citizens. Many people do not vote because they have seen or read poll projections and have decided that their votes will not make a difference. Furthermore, some critics of incessant polling argue that the public is just passively responding to surveys that mainly measure opinions on topics of interest to business, government, academics, and the mainstream news media. A final problem is the pervasive use of unreliable pseudo-

Social Psychology Studies

While opinion polls measure public attitudes, social psychology studies measure the behavior and cognition of individuals. The most influential early social psychology study, the Payne Fund Studies, encompassed a series of thirteen research projects conducted by social psychologists between 1929 and 1932. Named after the private philanthropic organization that funded the research, the Payne Fund Studies were a response to a growing national concern about the effects of motion pictures, which had become a particularly popular pastime for young people in the 1920s. These studies, which were later used by some politicians to attack the movie industry, linked frequent movie attendance to juvenile delinquency, promiscuity, and other antisocial behaviors, arguing that movies took “emotional possession” of young filmgoers.10

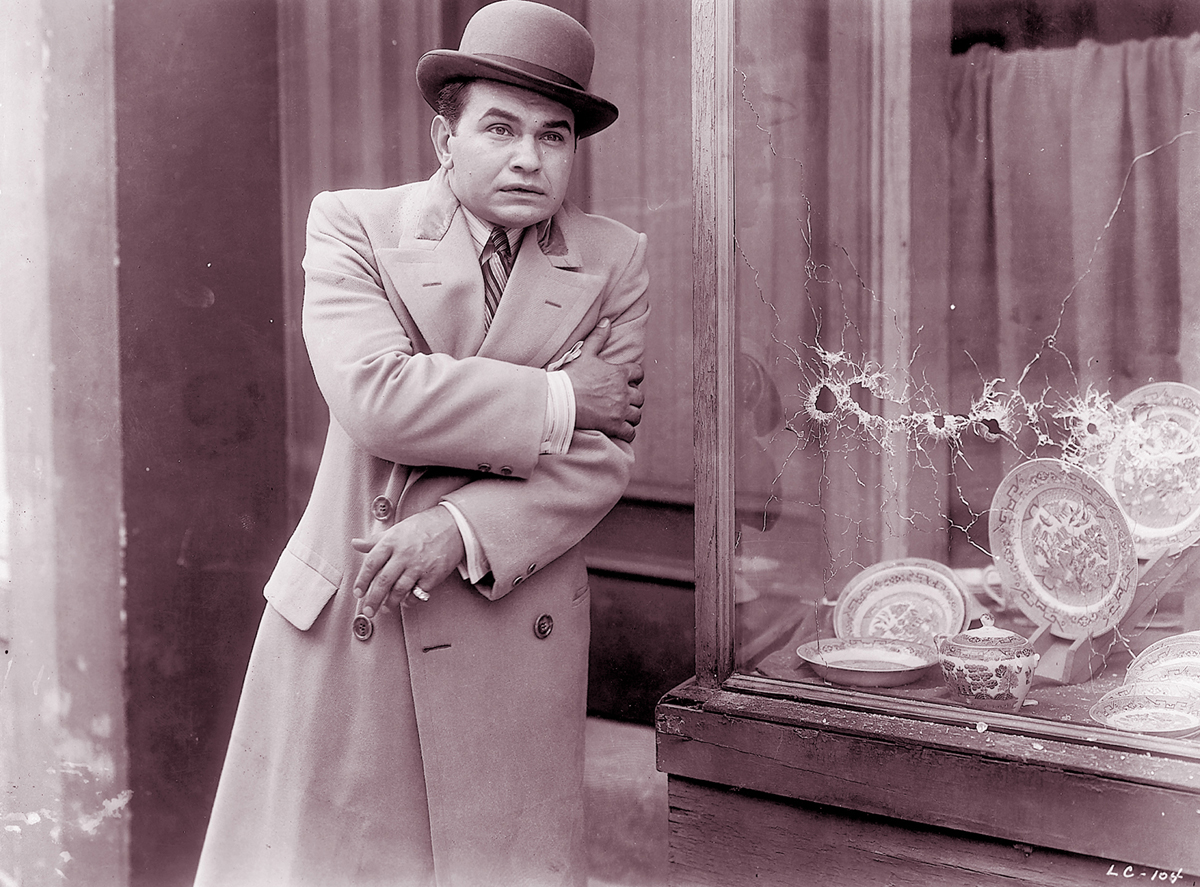

Concerns about film violence are not new. The 1930 movie Little Caesar follows the career of gangster Rico Bandello (played by Edward G. Robinson, shown), who kills his way to the top of the crime establishment and gets the girl as well. The Motion Picture Production Code, which was established a few years after this movie’s release, reined in sexual themes and profane language, set restrictions on film violence, and attempted to prevent audiences from sympathizing with bad guys like Rico. Photofest

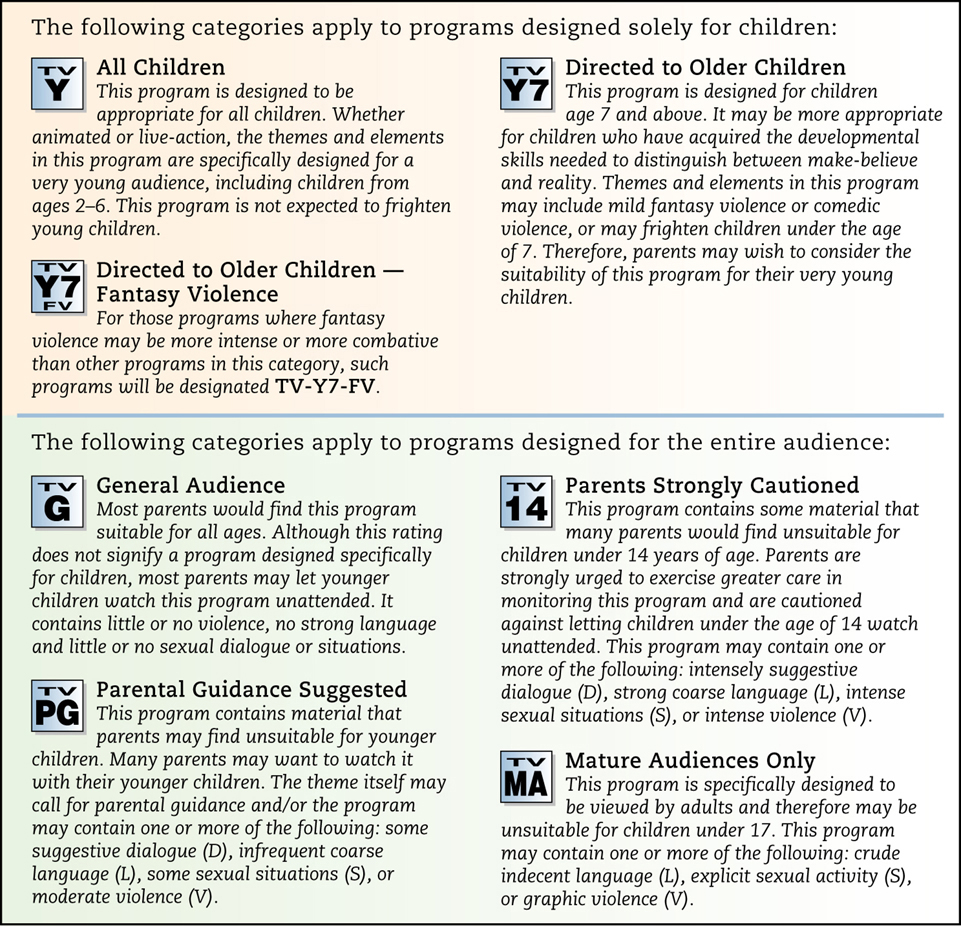

In one of the Payne studies, for example, children and teenagers were wired with electrodes and galvanometers, mechanisms that detected any heightened response via the subject’s skin. The researchers interpreted changes in the skin as evidence of emotional arousal. In retrospect, the findings hardly seem surprising: The youngest subjects in the group had the strongest reaction to violent or tragic movie scenes, while the teenage subjects reacted most strongly to scenes with romantic and sexual content. The researchers concluded that films could be dangerous for young children and might foster sexual promiscuity among teenagers. The conclusions of this and other Payne Fund Studies contributed to the establishment of the Motion Picture Production Code, which tamed movie content from the 1930s through the 1950s (see Chapter 16). As forerunners of today’s TV violence and aggression research, the Payne Fund Studies became the model for media research. (See Figure 15.1 for one example of a contemporary policy that has developed from media research. Also see “Case Study: The Effects of TV in a Post-TV World” on page 517.)

CASE STUDY

The Effects of TV in a Post-

Since TV’s emergence as a mass medium, there has been persistent concern about the effects of violence, sex, and indecent language seen in television programs. The U.S. Congress had its first hearings on the matter of television content in 1952 and has held hearings in every subsequent decade.

In its coverage of congressional hearings on TV violence in 1983, the New York Times accurately captured the nature of these recurring public hearings: “Over the years, the principals change but the roles remain the same: social scientists ready to prove that television does indeed improperly influence its viewers, and network representatives, some of them also social scientists, who insist that there is absolutely nothing to worry about.”1

One of the central focuses of the TV debate has been television’s effect on children. In 1975, the major broadcast networks (then ABC, CBS, and NBC) bowed to congressional and FCC pressure and agreed to a “family hour” of programming in the first hour of prime-

The most prominent watchdog monitoring prime-

Yet to address the ongoing concerns of parent groups and Congress, it’s worth asking: What are the effects of TV in what researchers now call a “post-

These days, the Parents Television Council still releases its weekly “Family Guide to Prime Time Television” on its Web site. A sample of its guide from summer 2014, for example, listed no shows as “family-

Of course, as television viewers move away from broadcast networks and increasingly watch programming from multiple sources on a range of devices, the PTC’s traditional concern about prime-

Marketing Research

A fourth influential area of early media research, marketing research, developed when advertisers and product companies began conducting surveys on consumer buying habits in the 1920s. The emergence of commercial radio led to the first ratings systems that measured how many people were listening on a given night. By the 1930s, radio networks, advertisers, large stations, and advertising agencies all subscribed to ratings services. However, compared with print media, whose circulation departments kept careful track of customers’ names and addresses, radio listeners were more difficult to trace. This problem precipitated the development of increasingly sophisticated marketing research methods to determine consumer preferences and media use, such as direct-