The Origins of Free Expression and a Free Press

During the Iraq War, journalists were embedded with troops to provide “frontline” coverage. The freedom the U.S. press had to report on the war came at a cost. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 249 journalists and media workers were killed in Iraq between 2003 and 2014 as a result of hostile actions. AP Photo/John Moore

When students from other cultures attend school in the United States, many are astounded by the number of books, news articles, editorials, cartoons, films, TV shows, and Web sites that make fun of U.S. presidents, the military, and the police. Many countries’ governments throughout history have jailed, or even killed, their citizens for such speech “violations.” For instance, between 1992 and September 2014, more than one thousand international journalists were killed in the line of duty, often because someone disagreed with what they wrote or reported.6 In the United States, however, we have generally taken for granted our right to criticize and poke fun at the government and other authority figures. Moreover, many of us are unaware of the ideas that underpin our freedoms and don’t realize the extent to which those freedoms surpass those in most other countries.

In fact, a 2014 survey related that sixty-

Models of Expression

Since the mid-

The authoritarian model developed at about the time the printing press first arrived in sixteenth-

Today, many authoritarian systems operate in developing countries throughout Asia, Latin America, and Africa, where journalism often joins with government and business to foster economic growth, minimize political dissent, and promote social stability, because state leaders believe that too much speech freedom would undermine the delicate stability of their nations’ social infrastructures. In these societies, criticizing government programs may be viewed as an obstacle to keeping the peace, and both reporters and citizens may be punished if they question leaders and the status quo too fiercely.

In the authoritarian model, the news is controlled by private enterprise. But under the communist or state model, the press is controlled by the government because state leaders believe the press should serve the goals of the state. Although some government criticism is tolerated under this model, ideas that challenge the basic premises of state authority are not. Although state media systems were in decline throughout the 1990s, there are still a few countries using this model, including Myanmar (Burma), China, Cuba, and North Korea.

The social responsibility model characterizes the ideals of mainstream journalism in the United States. The concepts and assumptions behind this model were outlined in 1947 by the Hutchins Commission, which was formed to examine the increasing influence of the press. The commission’s report called for the development of press watchdog groups because the mass media had grown too powerful and needed to become more socially responsible. Key recommendations encouraged comprehensive news reports that put issues and events in context; more news forums for the exchange of ideas; better coverage of society’s range of economic classes and social groups; and stronger overviews of our nation’s social values, ideals, and goals.

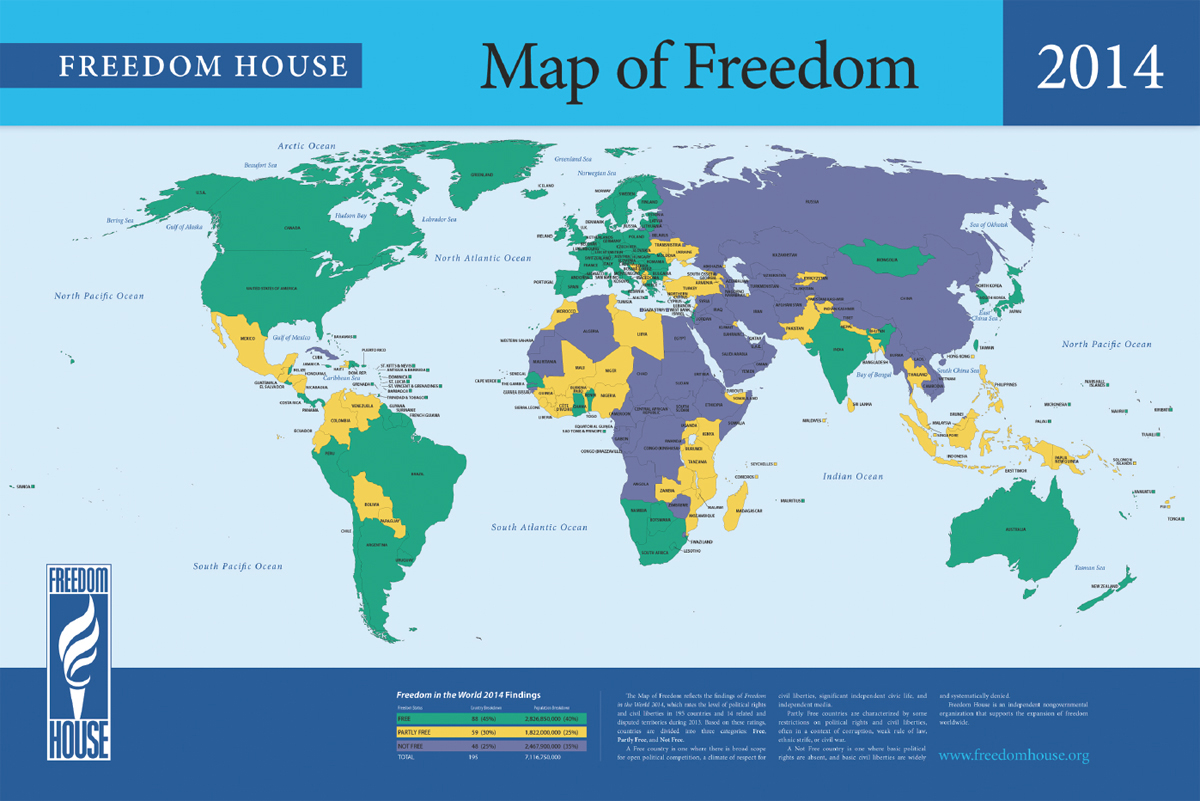

The international human rights organization Freedom House comparatively assesses political rights and civil liberties in 197 of the world’s countries and territories. Among the nations counted as not entirely free are China, Cuba, Iran, Iraq, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Courtesy of Freedom House

A socially responsible press is usually privately owned (although the government technically operates the broadcast media in most European democracies). In this model, the press functions as a Fourth Estate—that is, as an unofficial branch of government that monitors the legislative, judicial, and executive branches for abuses of power. In theory, private ownership keeps the news media independent of government. Thus they are better able to watch over the system on behalf of citizens. Under this model, the press supplies information to citizens so that they can make informed decisions regarding political and social issues.

The flip side of the state and authoritarian models and a more radical extension of the social responsibility model, the libertarian model encourages vigorous government criticism and supports the highest degree of individual and press freedoms. Under a libertarian model, no restrictions would be placed on the mass media or on individual speech. Libertarians tolerate the expression of everything, from publishing pornography to advocating anarchy. In North America and Europe, many alternative newspapers and magazines operate on such a model. Placing a great deal of trust in citizens’ ability to distinguish truth from fabrication, libertarians maintain that speaking out with absolute freedom is the best way to fight injustice and arrive at the truth.

The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution

To understand the development of free expression in the United States, we must first understand how the idea for a free press came about. In various European countries throughout the seventeenth century, in order to monitor—

Less than a hundred years later, the writers of the U.S. Constitution were ambivalent about the freedom of the press. In fact, the Constitution as originally ratified in 1788 didn’t include a guarantee of freedom of the press. Constitutional framer Alexander Hamilton thought it impractical to attempt to define “liberty of the press” and believed that whatever declarations might be added to the Constitution, its security would ultimately depend on public opinion. At that time, though, nine of the original thirteen states had charters defending the freedom of the press, and the states pushed to have federal guarantees of free speech and press approved at the first session of the new Congress. The Bill of Rights, which contained the first ten amendments to the Constitution, was adopted in 1791.

The commitment to freedom of the press, however, was not resolute. In 1798, the Federalist Party, which controlled the presidency and Congress, passed the Sedition Act to silence opposition to an anticipated war against France. Led by President John Adams, the Federalists believed that defamatory articles by the opposition Democratic-

Censorship as Prior Restraint

In the United States, the First Amendment has theoretically prohibited censorship. Over time, Supreme Court decisions have defined censorship as prior restraint. This means that courts and governments cannot block any publication or speech before it actually occurs, on the principle that a law has not been broken until an illegal act has been committed. In 1931, for example, the Supreme Court determined in Near v. Minnesota that a Minneapolis newspaper could not be stopped from publishing “scandalous and defamatory” material about police and law officials whom they felt were negligent in arresting and punishing local gangsters.11 However, the Court left open the idea that the news media could be ordered to halt publication in exceptional cases. During a declared war, for instance, if a U.S. court judged that the publication of an article would threaten national security, such expression could be restrained prior to its printing. In fact, during World War I, the U.S. Navy seized all wireless radio transmitters. This was done to ensure control over critical information about weather conditions and troop movements that might inadvertently aid the enemy. In the 1970s, though, the Pentagon Papers decision and the Progressive magazine case tested important concepts underlying prior restraint.

The Pentagon Papers Case

In 1971, with the Vietnam War still in progress, Daniel Ellsberg, a former Defense Department employee, stole a copy of the forty-

A lower U.S. district court supported the newspaper’s right to publish, but the government’s appeal put the case before the Supreme Court less than three weeks after the first article was published. In a six-

In 1971, Daniel Ellsberg surrendered to government prosecutors in Boston. Ellsberg was a former Pentagon researcher who turned against America’s military policy in Vietnam and leaked information to the press. He was charged with unauthorized possession of top-

The Progressive Magazine Case

The issue of prior restraint for national security surfaced again in 1979, when an injunction was issued to block publication of the Progressive, a national left-

Judge Robert Warren sought to balance the Progressive’s First Amendment rights against the government’s claim that the article would spread dangerous information and undermine national security. In an unprecedented action, Warren sided with the government, deciding that “a mistake in ruling against the United States could pave the way for thermonuclear annihilation for us all. In that event, our right to life is extinguished and the right to publish becomes moot.”13 During appeals and further litigation, several other publications, including the Milwaukee Sentinel and Scientific American, published their own articles related to the H-

Even though the article was eventually published, Warren’s decision stands as the first time in American history that a prior-

Unprotected Forms of Expression

Despite the First Amendment’s provision that “Congress shall make no law” restricting speech, the federal government has made a number of laws that do just that, especially concerning false or misleading advertising, expressions that intentionally threaten public safety, and certain speech that compromises war strategy and other issues of national security.

Beyond the federal government, state laws and local ordinances have on occasion curbed expression, and over the years the court system has determined that some kinds of expression do not merit protection under the Constitution, including seditious expression, copyright infringement, libel, obscenity, the right to privacy, and expression that interferes with the Sixth Amendment.

Media Literacy and the Critical Process

Who Knows the First Amendment?

Enacted in 1791, the First Amendment supports not just press and speech freedoms but also religious freedom and the right of people to protest and to “petition the government for a redress of grievances.” It also says that “Congress shall make no law” abridging or prohibiting these five freedoms. To investigate some critics’ charge that many citizens don’t exactly know the protections offered in the First Amendment, conduct your own survey. Discuss with friends, family, or colleagues what they know or think about the First Amendment.

1 DESCRIPTION. Working alone or in small groups, find eight to ten people you know from two different age groups: (1) from your peers and friends or younger siblings, and (2) from your parents’ or grandparents’ generations. (Do not choose students from your class.) Interview your subjects individually, in person, by phone, or by e-

- Do you agree or disagree with the freedoms? Explain.

- Which do you support, and which do you think are excessive or provide too much freedom?

- Ask them if they recognize the law. Note how many identify it as the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and how many do not. Note the percentage from each age group.

- Optional: Ask if your respondents are willing to share their political leanings—

Republican, Democrat, Independent, not sure, disaffected, apathetic, or other. Record their answers.

2 ANALYSIS. What patterns emerge in the answers from the two groups? Are their answers similar or different? How? Note any differences in the answers based on gender, level of education, or occupation.

3 INTERPRETATION. What do these patterns mean? Are your interview subjects supportive or unsupportive of the First Amendment? What are their reasons?

4 EVALUATION. How do your interviewees judge the freedoms? In general, what did your interview subjects know about the First Amendment? What impresses you about your subjects’ answers? Do you find anything alarming or troubling in their answers?

5 ENGAGEMENT. Research free expression and locate any national studies that are similar to this assignment. Then, check the recent national surveys on attitudes toward the First Amendment at www.newseuminstitute.org/

Seditious Expression

For more than a century after the Sedition Act of 1798, Congress passed no laws prohibiting dissenting opinion. But by the twentieth century, the sentiments of the Sedition Act reappeared in times of war. For instance, the Espionage Acts of 1917 and 1918, which were enforced during World Wars I and II, made it a federal crime to disrupt the nation’s war effort, authorizing severe punishment for seditious statements.

In the landmark Schenck v. United States (1919) appeal case during World War I, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of a Socialist Party leader, Charles T. Schenck, for distributing leaflets urging American men to protest the draft, in violation of the recently passed Espionage Act. In upholding the conviction, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote two of the more famous interpretations and phrases in the First Amendment’s legal history:

But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theater and causing a panic.

The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.

In supporting Schenck’s sentence—

And in 2010, after WikiLeaks released thousands of confidential U.S. embassy cables into the public domain, the U.S. Justice Department contemplated charging the Web site’s founder, Julian Assange, with violating the 1917 Espionage Act. In June 2012, Assange took refuge inside the Ecuadorian embassy in London, where he was granted diplomatic asylum. The U.S. government instead pursued Espionage Act charges against Private First Class Bradley (now Chelsea) Manning, an intelligence analyst in Iraq, who admitted to releasing the information to WikiLeaks to show the flaws of U.S. strategies in Iraq and Afghanistan. Manning was convicted and sentenced to thirty-

Copyright Infringement

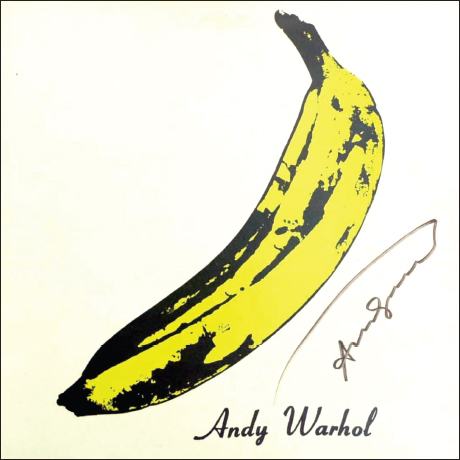

The iconic album art for the Velvet Underground’s 1967 debut, a banana print designed by artist Andy Warhol, has been a subject of controversy in recent years, as a copyright dispute between the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the rock band has continued to flourish. The most recent disagreement occurred when the Warhol Foundation, which had previously accused the Velvet Underground of violating its claim to the print, announced plans to license the banana design for iPhone cases. Accusing the foundation of copyright violation, the band filed a copyright claim to the design, which a federal judge later dismissed. Camera Press/Richard Stonehouse/Redux Pictures

Appropriating a writer’s or an artist’s words or music without consent or payment is also a form of expression that is not protected as speech. A copyright legally protects the rights of authors and producers to their published or unpublished writing, music, lyrics, TV programs, movies, or graphic art designs. When Congress passed the first Copyright Act in 1790, it gave authors the right to control their published works for fourteen years, with the opportunity for a renewal for another fourteen years. After the end of the copyright period, the work enters the public domain, which gives the public free access to the work. The idea was that a period of copyright control would give authors financial incentive to create original works, and that the public domain gives others incentive to create derivative works.

Over the years, as artists lived longer and, more important, as corporate copyright owners became more common, copyright periods were extended by Congress. In 1976, Congress extended the copyright period to the life of the author plus fifty years, or seventy-

Corporate owners have millions of dollars to gain by keeping their properties out of the public domain. Disney, a major lobbyist for the 1998 extension, would have lost its copyright to Mickey Mouse in 2004 but now continues to earn millions on its movies, T-

Today, nearly every innovation in digital culture creates new questions about copyright law. For example, is a video mash-

Libel

The 1960 New York Times advertisement that triggered one of the most influential and important libel cases in U.S. history criticized law-

The biggest legal worry that haunts editors and publishers is the issue of libel, a form of expression that, unlike political expression, is not protected as free speech under the First Amendment. Libel refers to defamation of character in written or broadcast form; libel is different from slander, which is spoken language that defames a person’s character. Inherited from British common law, libel is generally defined as a false statement that holds a person up to public ridicule, contempt, or hatred or injures a person’s business or occupation. Examples of libelous statements include falsely accusing someone of professional dishonesty or incompetence (such as medical malpractice), falsely accusing a person of a crime (such as drug dealing), falsely stating that someone is mentally ill or engages in unacceptable behavior (such as public drunkenness), or falsely accusing a person of associating with a disreputable organization or cause (such as the Mafia or a neo-

Since 1964, the New York Times v. Sullivan case has served as the standard for libel law. The case stems from a 1960 full-

As part of the Sullivan decision, the Supreme Court asked future civil courts to distinguish whether plaintiffs in libel cases are public officials or private individuals. Citizens with more “ordinary” jobs, such as city sanitation employees, undercover police informants, nurses, or unknown actors, are normally classified as private individuals. Private individuals have to prove (1) that the public statement about them was false, (2) that damages or actual injury occurred (such as the loss of a job, harm to reputation, public humiliation, or mental anguish), and (3) that the publisher or broadcaster was negligent in failing to determine the truthfulness of the statement.

There are two categories of public figures: (1) public celebrities (movie or sports stars) or people who “occupy positions of such pervasive power and influence that they are deemed public figures for all purposes” (presidents, senators, mayors), and (2) individuals who have thrown themselves—

Public officials also have to prove falsehood, damages, negligence, and actual malice on the part of the news medium; actual malice means that the reporter or editor knew the statement was false and printed or broadcast it anyway, or acted with a reckless disregard for the truth. Because actual malice against a public official is hard to prove, it is difficult for public figures to win libel suits. The Sullivan decision allowed news operations to aggressively pursue legitimate news stories without fear of continuous litigation. However, the mere threat of a libel suit still scares off many in the news media. Plaintiffs may also belong to one of many vague classification categories, such as public high school teachers, police officers, and court-

Defenses against Libel Charges

Since the 1730s, the best defense against libel in American courts has been the truth. In most cases, if libel defendants can demonstrate that they printed or broadcast statements that were essentially true, such evidence usually bars plaintiffs from recovering any damages—

In addition, there are other defenses against libel. Prosecutors, for example, who would otherwise be vulnerable to being accused of libel are granted absolute privilege in a court of law so that they are not prevented from making accusatory statements toward defendants. The reporters who print or broadcast statements made in court are also protected against libel; they are granted conditional or qualified privilege, allowing them to report judicial or legislative proceedings even though the public statements being reported may be libelous.

Another defense against libel is the rule of opinion and fair comment. Generally, libel applies only to intentional misstatements of factual information rather than opinion, and therefore opinions are protected from libel. However, because the line between fact and opinion is often hazy, lawyers advise journalists first to set forth the facts on which a viewpoint is based and then to state their opinion based on those facts. In other words, journalists should make it clear that a statement of opinion is a criticism and not an allegation of fact.

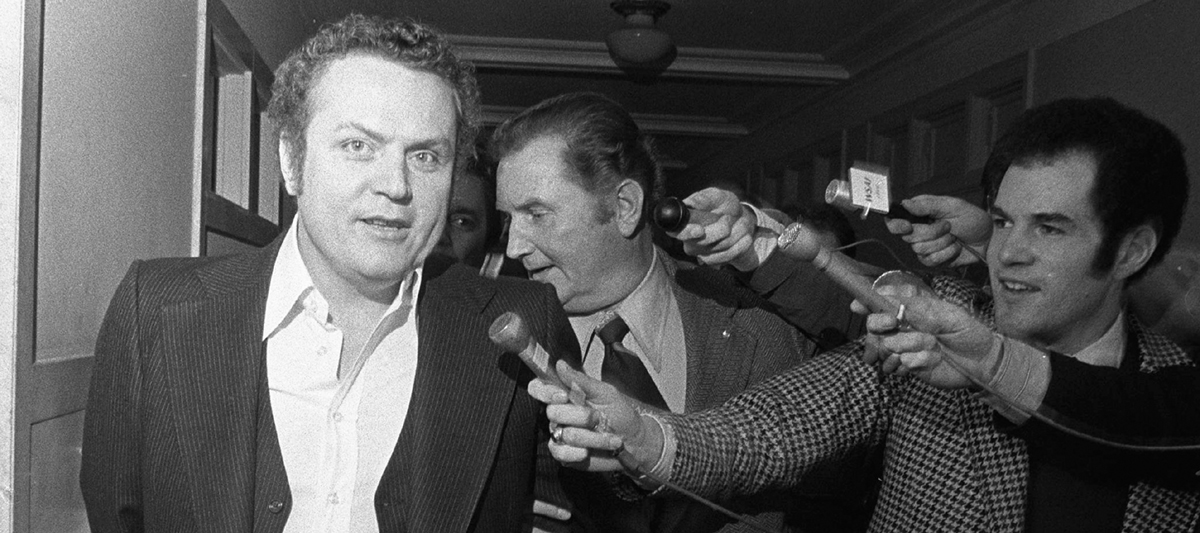

Prior to his 1984 libel trial, Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt was also convicted of pandering obscenity. Here, Flynt answers questions from newsmen on February 9, 1977, as he is led to jail. AP Photo/BH

One of the most famous tests of opinion and fair comment occurred in 1983, when Larry Flynt, publisher of Hustler magazine, published a spoof of a Campari advertisement depicting conservative minister and political activist Jerry Falwell as a drunk and as having had sexual relations with his mother. In fine print at the bottom of the page, a disclaimer read: “Ad parody—

Libel laws also protect satire, comedy, and opinions expressed in reviews of books, plays, movies, and restaurants. Such laws may not, however, protect malicious statements in which plaintiffs can prove that defendants used their free-

Obscenity

For most of this nation’s history, legislators have argued that obscenity does not constitute a legitimate form of expression protected by the First Amendment. The problem, however, is that little agreement has existed on how to define an obscene work. In the 1860s, a court could judge an entire book obscene if it contained a single passage believed capable of “corrupting” a person. In fact, throughout the nineteenth century, certain government authorities outside the courts—

This began to change in the 1930s, during the trial involving the celebrated novel Ulysses by Irish writer James Joyce. Portions of Ulysses had been serialized in the early 1920s in an American magazine, Little Review, copies of which were later seized and burned by postal officials. The publishers of the magazine were fined $50 and nearly sent to prison. Because of the four-

In a landmark 1957 case, Roth v. United States, the Supreme Court offered this test of obscenity: whether to an “average person,” applying “contemporary standards,” the major thrust or theme of the material “taken as a whole” appealed to “prurient interest” (in other words, was intended to “incite lust”). By the 1960s, based on Roth, expression was not obscene if only a small part of the work lacked “redeeming social value.”

The current legal definition of obscenity derives from the 1973 Miller v. California case, which stated that to qualify as obscenity, the material must meet three criteria: (1) the average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find that the material as a whole appeals to prurient interest; (2) the material depicts or describes sexual conduct in a patently offensive way; and (3) the material, as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. The Miller decision contained two important ideas not present in Roth. First, it acknowledged that different communities and regions of the country have different values and standards with which to judge obscenity. Second, it required that a work be judged as a whole, so that publishers could not use the loophole of inserting a political essay or literary poem into pornographic materials to demonstrate in court that their publications contained redeeming features.

Since the Miller decision, courts have granted great latitude to printed and visual obscenity. By the 1990s, major prosecutions had become rare—

The Right to Privacy

Prince William and Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, have been an object of ongoing fascination since marrying in 2011. The media frenzy surrounding the royal couple came to a head when the French tabloid Closer published images of what appears to be the Duchess sunbathing topless while on vacation, prompting the royal family to press criminal charges against the publication. A greater frenzy accompanied the birth of the couple’s first child in 2013. The British royal family is sadly all too familiar with the paparazzi; Prince William’s mother, Diana, Princess of Wales, died in a car accident after being chased by paparazzi in 1997. Vincent Thian/AFP/Getty Images

Whereas libel laws safeguard a person’s character and reputation, the right to privacy protects an individual’s peace of mind and personal feelings. In the simplest terms, the right to privacy addresses a person’s right to be left alone, without his or her name, image, or daily activities becoming public property. Invasions of privacy occur in different situations, the most common of which are intrusion into someone’s personal space via unauthorized tape recording, photographing, wiretapping, and the like; making available to the public personal records, such as health and phone records; disclosing personal information, such as religion, sexual activities, or personal activities; and unauthorized appropriation of someone’s image or name for advertising or other commercial purposes. In general, the news media have been granted wide protections under the First Amendment to do their work. For instance, the names and pictures of both private individuals and public figures can usually be used without their consent in most news stories. Additionally, if private citizens become part of public controversies and subsequent news stories, the courts have usually allowed the news media to treat them like public figures (that is, to record their quotes and use their images without the individuals’ permission). The courts have even ruled that accurate reports of criminal and court records, including the identification of rape victims, do not normally constitute privacy invasions. Nevertheless, most newspapers and broadcast outlets use their own internal guidelines and ethical codes to protect the privacy of victims and defendants, especially in cases involving rape and child abuse.

Public figures, however, have received some legal relief, as many local municipalities and states have passed “anti-

A number of laws also protect the privacy of regular citizens. For example, the Privacy Act of 1974 protects individuals’ records from public disclosure unless individuals give written consent. The Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 extended the law to computer-

CASE STUDY

Is “Sexting” Pornography?

According to U.S. federal and state laws, when someone produces, transmits, or possesses images with graphic sexual depictions of minors, it is considered child pornography. Digital media have made the circulation of child pornography even more pervasive, according to a 2006 study on child pornography on the Internet. About one thousand people are arrested each year in the United States for child pornography, and according to a U.S. Department of Justice guide for police, they have few distinguishing characteristics other than being “likely to be white, male, and between the ages of 26 and 40.”1

Now, a social practice has challenged the common wisdom of what is obscenity and who are child pornographers: What happens when the people who produce, transmit, and possess images with graphic sexual depictions of minors are minors themselves?

The practice in question is “sexting,” the sending or receiving of sexual images via mobile phone text messages or via the Internet. Sexting occupies a gray area of obscenity law—

While such messages are usually meant to be completely personal, technology makes it otherwise. “All control over the image is lost—

A recent national survey found that 15 percent of teens ages twelve to seventeen say they have received sexually suggestive nude or nearly nude images of someone they know via text messaging. Another 4 percent of teens ages twelve to seventeen say they have sent sexually suggestive nude or nearly nude images of themselves via text messaging. The rates are even higher for teens at age seventeen—

Some recent cases illustrate how young people engaging in sexting have gotten caught up in a legal system designed to punish pedophiles. In 2008, Florida resident Phillip Alpert, then eighteen, sent nude images of his sixteen-

First Amendment versus Sixth Amendment

Over the years, First Amendment protections of speech and the press have often clashed with the Sixth Amendment, which guarantees an accused individual in “all criminal prosecutions . . . the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury.” In 1954, for example, the Sam Sheppard case garnered enormous nationwide publicity and became the inspiration for the TV show and film The Fugitive. Featuring lurid details about the murder of Sheppard’s wife, the press editorialized in favor of Sheppard’s quick arrest; some papers even pronounced him guilty. A prominent and wealthy osteopath, Sheppard was convicted of the murder, but twelve years later Sheppard’s new lawyer, F. Lee Bailey, argued before the Supreme Court that his client had not received a fair trial because of prejudicial publicity in the press. The Court overturned the conviction and freed Sheppard.

Gag Orders and Shield Laws

A major criticism of recent criminal cases concerns the ways in which lawyers use the news media to comment publicly on cases that are pending or are in trial. After the Sheppard reversal in the 1960s, the Supreme Court introduced safeguards that judges could employ to ensure fair trials in heavily publicized cases. These included sequestering juries (Sheppard’s jury was not sequestered); moving cases to other jurisdictions; limiting the number of reporters; and placing restrictions, or gag orders, on lawyers and witnesses. In some countries, courts have issued gag orders to prohibit the press from releasing information or giving commentary that might prejudice jury selection or cause an unfair trial. In the United States, however, especially since a Supreme Court review in 1976, gag orders have been struck down as a prior-

In opposition to gag orders, shield laws have favored the First Amendment rights of reporters, protecting them from having to reveal their sources for controversial information used in news stories. The news media have argued that protecting the confidentiality of key sources maintains a reporter’s credibility, protects a source from possible retaliation, and serves the public interest by providing information that citizens might not otherwise receive. In the 1960s, when the First Amendment rights of reporters clashed with Sixth Amendment fair-

Cameras in the Courtroom

The debates over limiting intrusive electronic broadcast equipment and photographers in the courtroom actually date to the sensationalized coverage of the Bruno Hauptmann trial in the mid-

After the trial, the American Bar Association amended its professional ethics code, Canon 35, stating that electronic equipment in the courtroom detracted “from the essential dignity of the proceedings.” Calling for a ban on photographers and radio equipment, the association believed that if such elements were not banned, lawyers would begin playing to audiences and negatively alter the judicial process. For years after the Hauptmann trial, almost every state banned photographic, radio, and TV equipment from courtrooms.

As broadcast equipment became more portable and less obtrusive, however, and as television became the major news source for most Americans, courts gradually reevaluated their bans on broadcast equipment. In fact, in the early 1980s, the Supreme Court ruled that the presence of TV equipment did not make it impossible for a fair trial to occur, leaving it up to each state to implement its own system. The ruling opened the door for the debut of Court TV (now truTV) in 1991 and the televised O.J. Simpson trial of 1994 (the most publicized case in history). All states today allow television coverage of cases, although most states place certain restrictions on coverage of courtrooms, often leaving it up to the discretion of the presiding judge. While U.S. federal courts now allow limited TV coverage of their trials, the Supreme Court continues to ban TV from its proceedings, but in 2000 the Court broke its anti-

As libel law and the growing acceptance of courtroom cameras indicate, the legal process has generally, though not always, tried to ensure that print and other news media are able to cover public issues broadly, without fear of reprisals.

Photographers surround aviator Charles A. Lindbergh (without hat) as he leaves the courthouse in Flemington, New Jersey, during the trial in 1935 of Bruno Hauptmann on charges of kidnapping and murdering Lindbergh’s infant son. AP Images