The Development of Media and Their Role in Our Society

The mass media constitute a wide variety of industries and merchandise, from moving documentary news programs about famines in Africa to shady infomercials about how to retrieve millions of dollars in unclaimed money online. The word media is, after all, a Latin plural form of the singular noun medium, meaning an intervening substance through which something is conveyed or transmitted. Television, newspapers, music, movies, magazines, books, billboards, radio, broadcast satellites, and the Internet are all part of the media, and they are all quite capable of either producing worthy products or pandering to society’s worst desires, prejudices, and stereotypes. Let’s begin by looking at how mass media develop, and then at how they work and are interpreted in our society.

The Evolution of Media: From Emergence to Convergence

The development of most mass media is initiated not only by the diligence of inventors, such as Thomas Edison (see Chapters 4 and 7), but also by social, cultural, political, and economic circumstances. For instance, both telegraph and radio evolved as newly industrialized nations sought to expand their military and economic control and to transmit information more rapidly. The Internet is a contemporary response to new concerns: transporting messages and sharing information more rapidly for an increasingly mobile and interconnected global population.

Media innovations typically go through four stages. First is the emergence, or novelty, stage, in which inventors and technicians try to solve a particular problem, such as making pictures move, transmitting messages from ship to shore, or sending mail electronically. Second is the entrepreneurial stage, in which inventors and investors determine a practical and marketable use for the new device. For example, early radio relayed messages to and from places where telegraph wires could not go, such as military ships at sea. Part of the Internet also had its roots in the ideas of military leaders, who wanted a communication system that was decentralized and distributed widely enough to survive nuclear war or natural disasters.

The third phase in a medium’s development involves a breakthrough to the mass medium stage. At this point, businesses figure out how to market the new device or medium as a consumer product. Although the government and the U.S. Navy played a central role in radio’s early years, it was commercial entrepreneurs who pioneered radio broadcasting and figured out how to reach millions of people. In the same way, Pentagon and government researchers helped develop early prototypes for the Internet, but commercial interests extended the Internet’s global reach and business potential.

Finally, the fourth and newest phase in a medium’s evolution is the convergence stage. This is the stage in which older media are reconfigured in various forms on newer media. However, this does not mean that these older forms cease to exist. For example, you can still get the New York Times in print, but it’s also now accessible on laptops and smartphones via the Internet. During this stage, we see the merging of many different media forms onto online platforms, but we also see the fragmenting of large audiences into smaller niche markets. With new technologies allowing access to more media options than ever, mass audiences are morphing into audience subsets that chase particular lifestyles, politics, hobbies, and forms of entertainment.

Media Convergence

Developments in the electronic and digital eras enabled and ushered in this latest stage in the development of media—

The Dual Roles of Media Convergence

The first definition of media convergence involves the technological merging of content across different media channels—

In the 1950s, television sets—

Such technical convergence is not entirely new. For example, in the late 1920s, the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) purchased the Victor Talking Machine Company and introduced machines that could play both radio and recorded music. In the 1950s, this collaboration helped radio survive the emergence of television. Radio lost much of its content to TV and could not afford to hire live bands, so it became more dependent on deejays to play records produced by the music industry. However, contemporary media convergence is much broader than the simple merging of older and newer forms. In fact, the eras of communication are themselves reinvented in this “age of convergence.” Oral communication, for example, finds itself reconfigured, in part, in e-

A second definition of media convergence—

Media Businesses in a Converged World

The ramifications of media convergence are best revealed in the business strategies of digital age companies like Amazon, Facebook, Apple, and especially Google—

Today’s converged media world has broken down the old definitions of distinct media forms like newspapers and television—

Media Convergence and Cultural Change

The Internet and social media have led to significant changes in the ways we consume and engage with media culture. In the pre-

The ability to access many different forms of media in one place is also changing the ways we engage with and consume media. In the past, we read newspapers in print, watched TV on our televisions, and played video games on a console. Today, we are able to do all these things on a computer, tablet, or smartphone, making it easy—

However, media multitasking could have other effects. In the past, we would wait until the end of a TV program, if not until the next day, to discuss it with our friends. Now, with the proliferation of social media, and in particular Twitter, we can discuss that program with our friends—

Stories: The Foundation of Media

The stories that circulate in the media can shape a society’s perceptions and attitudes. Throughout the twentieth century and during the recent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, for instance, courageous professional journalists covered armed conflicts, telling stories that helped the public comprehend the magnitude and tragedy of such events. In the 1950s and 1960s, network television news stories on the Civil Rights movement led to crucial legislation that transformed the way many white people viewed the grievances and aspirations of African Americans. In the late 1960s to early 1970s, the persistent media coverage of the Vietnam War ultimately led to a loss of public support for the war. In the late 1990s, news and tabloid magazine stories about the President Clinton–

While we continue to look to the media for narratives today, the kinds of stories we seek and tell are changing in the digital era. During Hollywood’s Golden Age in the 1930s and 1940s, as many as ninety million people each week went to the movies on Saturday to take in a professionally produced double feature and a newsreel about the week’s main events. In the 1980s, during TV’s Network Era, most of us sat down at night to watch the polished evening news or the scripted sitcoms and dramas written by paid writers and performed by seasoned actors. But in the digital age, where reality TV and social media now seem to dominate storytelling, many of the performances are enacted by “ordinary” people. Audiences are fascinated by the stories of couples finding love, relationships gone bad, and backstabbing friends on shows like the Real Housewives series and its predecessors, like Jersey Shore. Other reality shows—

Online, many of us are entertaining each other with videos of our pets, Facebook posts about our achievements or relationship issues, photos of a good meal, or tweets about a funny thing that happened at work. This cultural blending of old and new ways of telling stories—

The Power of Media Stories in Everyday Life

The earliest debates, at least in Western society, about the impact of cultural narratives on daily life date back to the ancient Greeks. Socrates, himself accused of corrupting young minds, worried that children exposed to popular art forms and stories “without distinction” would “take into their souls teachings that are wholly opposite to those we wish them to be possessed of when they are grown up.”14 He believed art should uplift us from the ordinary routines of our lives. The playwright Euripides, however, believed that art should imitate life, that characters should be “real,” and that artistic works should reflect the actual world—

On October 21, 1967, a crowd of 100,000 protesters marched on the Pentagon demanding the end of the Vietnam War. Sadly, violence erupted when some protesters clashed with the U.S. Marshals protecting the Pentagon. However, this iconic image from the same protest appeared in the Washington Post the next day and went on to become a symbol for the peaceful ideals behind the protests. When has an image in the media made an event “real” to you? Marc Riboud/Magnum Photos

LaunchPad

Agenda Setting and Gatekeeping

Experts discuss how the media exert influence over public discourse.

Discussion: How might the rise of the Internet cancel out or reduce the agenda-

In The Republic, Plato developed the classical view of art: It should aim to instruct and uplift. He worried that some staged performances glorified evil and that common folk watching might not be able to distinguish between art and reality. Aristotle, Plato’s student, occupied a middle ground in these debates, arguing that art and stories should provide insight into the human condition but should entertain as well.

The cultural concerns of classical philosophers are still with us. In the early 1900s, for example, newly arrived immigrants to the United States who spoke little English gravitated toward cultural events (such as boxing, vaudeville, and the emerging medium of silent film) whose enjoyment did not depend solely on understanding English. Consequently, these popular events occasionally became a flash point for some groups, including the Daughters of the American Revolution, local politicians, religious leaders, and police vice squads, who not only resented the commercial success of immigrant culture but also feared that these “low” cultural forms would undermine what they saw as traditional American values and interests.

In the United States in the 1950s, the emergence of television and rock and roll generated several points of contention. For instance, the phenomenal popularity of Elvis Presley set the stage for many of today’s debates over hip-

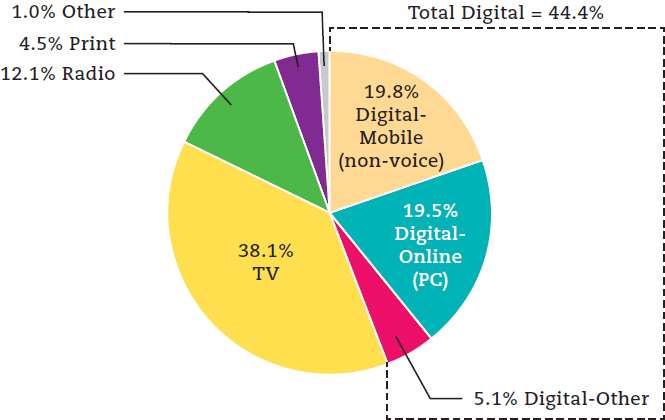

Today, with the reach of print, electronic, and digital communications and the amount of time people spend consuming them (see Figure 1.1 on page 16), mass media play an even more controversial role in society. Many people are critical of the quality of much contemporary culture and are concerned about the overwhelming amount of information now available. Many see popular media culture as unacceptably commercial and sensationalistic. Too many talk shows exploit personal problems for commercial gain, reality shows often glamorize outlandish behavior and dangerous stunts, and television research continues to document a connection between aggression in children and violent entertainment programs or video games. Children, who watch nearly forty thousand TV commercials each year, are particularly vulnerable to marketers selling junk food, toys, and “cool” clothing. Even the computer, once heralded as an educational salvation, has created confusion. Today, when kids announce that they are “on the computer,” many parents wonder whether they are writing a term paper, playing a video game, chatting on Facebook, or peering at pornography.

Yet how much the media shape society—

With American mass media industries earning more than $200 billion annually, the economic and societal stakes are high. Large portions of media resources now go toward studying audiences, capturing their attention through stories, and taking their consumer dollars. To increase their revenues, media outlets try to influence everything from how people shop to how they vote. Like the air we breathe, the commercially based culture that mass media help create surrounds us. Its impact, like the air, is often taken for granted. But to monitor that culture’s “air quality”—to become media literate—