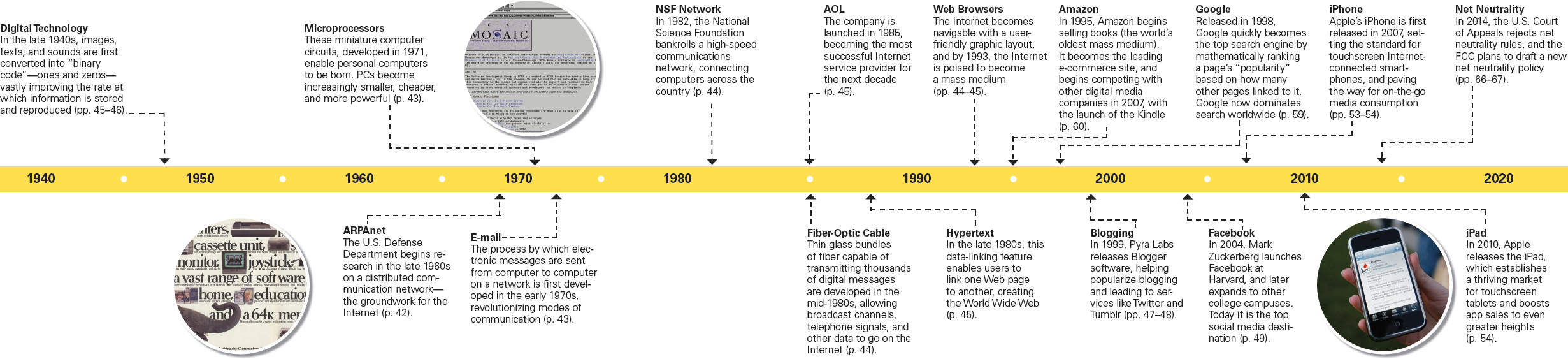

The Development of the Internet and the Web

From its humble origins as a military communications network in the 1960s, the Internet became increasingly interactive by the 1990s, allowing immediate two-

The Birth of the Internet

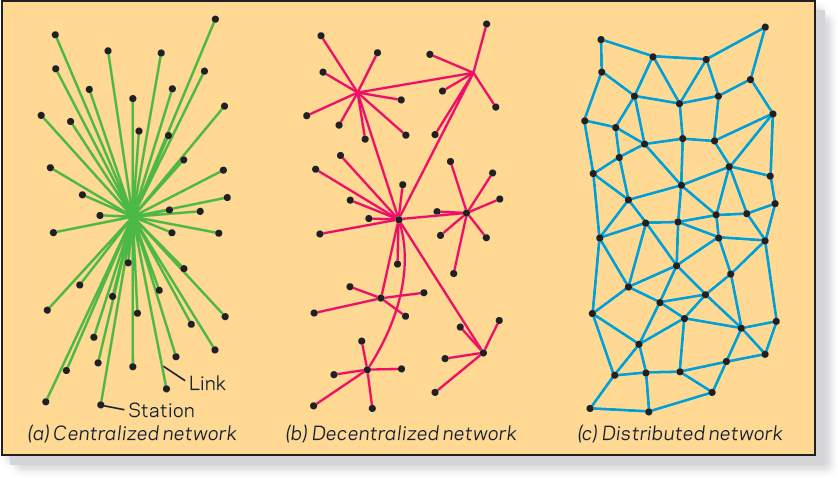

The Internet originated as a military-

Ironically, one of the most hierarchically structured and centrally organized institutions in our culture—

To enable military personnel and researchers involved in the development of ARPAnet to better communicate with one another from separate locations, an essential innovation during the development stage of the Internet was e-

At this point in the development stage, the Internet was primarily a tool for universities, government research labs, and corporations involved in computer software and other high-

The Net Widens

From the early 1970s until the late 1980s, a number of factors (both technological and historical) brought the Net to the entrepreneurial stage, in which it became a marketable medium. The first signal of the Net’s marketability came in 1971 with the introduction of microprocessors, miniature circuits that process and store electronic signals. This innovation facilitated the integration of thousands of transistors and related circuitry into thin strands of silicon along which binary codes traveled. Using microprocessors, manufacturers were eventually able to introduce the first personal computers (PCs), which were smaller, cheaper, and more powerful than the bulky computer systems of the 1960s. With personal computers now readily available, a second opportunity for marketing the Net came in 1986, when the National Science Foundation developed a high-

This advertisement for the Commodore 64, one of the first home PCs, touts the features of the computer. Although it was heralded in its time, today’s PCs far exceed its abilities. Image courtesy of the Advertising Archives

In the mid-

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s, the ARPAnet military venture officially ended. By that time, a growing community of researchers, computer programmers, amateur hackers, and commercial interests had already tapped into the Net, creating tens of thousands of points on the network and the initial audience for its emergence as a mass medium.

The Commercialization of the Internet

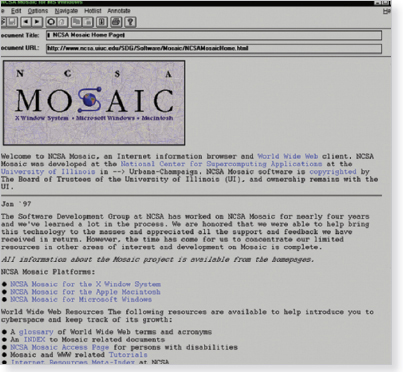

The introduction of the World Wide Web and the first Web browsers, Mosaic and Netscape, in the 1990s helped transform the Internet into a mass medium. Soon after these developments, the Internet quickly became commercialized, leading to battles between corporations vying to attract the most users, and others who wished to preserve the original public, nonprofit nature of the Net.

The World Begins to Browse

The GUI (graphical user interface) of the World Wide Web changed overnight with the release of Mosaic in 1993. As the first popular Web browser, Mosaic unleashed the multimedia potential of the Internet. Mosaic was the inspiration for the commercial browser Netscape, which was released in 1994. Courtesy of the National Center for Supercomputing Applications and the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois.

Prior to the 1990s, most of the Internet’s traffic was for e-

The release of Web browsers—the software packages that help users navigate the Web—

As the Web became the most popular part of the Internet, many thought that the key to commercial success on the Net would be through a Web browser. In 1995, Microsoft released its own Web browser, Internet Explorer, and within a few years, Internet Explorer—

Users Link in through Telephone and Cable Wires

In the first decades of the Internet, most people connected to “cyberspace” through telephone wires. AOL (formerly America Online) began connecting millions of home users in 1985 to its proprietary Web system through dial-

People Embrace Digital Communication

In digital communication, an image, a text, or a sound is converted into electronic signals represented as a series of binary numbers—

In the early days of e-

E-

Instant messaging, or IM, remains the easiest way to communicate over the Internet in real time and has become increasingly popular as a smartphone and tablet app, with free IM services supplanting costly text messages. Major IM services—

Search Engines Organize the Web

As the number of Web sites on the Internet quickly expanded, companies seized the opportunity to provide ways to navigate this vast amount of information by providing directories and search engines. One of the more popular search engines, Yahoo!, began as a directory. In 1994, Stanford University graduate students Jerry Yang and David Filo created a Web page—

Eventually, though, having employees catalog individual Web sites became impractical. Search engines offer a more automated route to finding content by allowing users to enter key words or queries to locate related Web pages. Search engines are built on mathematic algorithms. Google, released in 1998, became a major success because it introduced a new algorithm that mathematically ranked a page’s “popularity” on the basis of how many other pages linked to it. Google later moved to maintain its search dominance with its Google Voice Search and Google Goggles apps, which allow smartphone users to conduct searches by voicing search terms or by taking a photo. By 2014, Google’s global market share accounted for nearly 70 percent of searches, while China’s Baidu claimed 16.8 percent, Yahoo! reached 6.5 percent, and Microsoft’s Bing claimed about 6 percent.9