The Economics and Issues of the Internet

One of the unique things about the Internet is that no one owns it. But that hasn’t stopped some corporations from trying to control it. Since the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which overhauled the nation’s communications regulations, most regional and long-

Ownership and control of the Internet are connected to three Internet issues that command much public attention: the security of personal and private information, the appropriateness of online materials, and the accessibility and openness of the Internet. Important questions have been raised: Should personal or sensitive government information be private, or should the Internet be an enormous public record? Should the Internet be a completely open forum, or should certain types of communications be limited or prohibited? Should all people have equal access to the Internet, or should it be available only to those who can afford it? For each of these issues, there have been heated debates but no easy resolutions.

Ownership: Controlling the Internet

By the end of the 1990s, four companies—

Since the end of the 1990s, the Internet’s digital turn toward convergence has changed the Internet and the fortunes of its original leading companies. While AOL’s early success led to the huge AOL–

In today’s converged world, in which mobile access to digital content prevails, Microsoft and Google still remain powerful. Those two, along with Apple, Amazon, and Facebook, constitute the leading companies of digital media’s rapidly changing world. Of the five, all but Facebook also operate proprietary cloud services and encourage their customers to store all their files in their “walled garden” for easy access across all devices. This ultimately builds brand loyalty and generates customer fees for file storage.23

| ELSEWHERE IN MEDIA & CULTURE | |

The cathode- p. 190 |

25% how much of a $60 video game goes to art and design p. 103 |

|

WHO DECIDES WHAT INFORMATION IS LEGAL FOR CORPORATIONS TO USE? p. 448 |

|

|

7.4 cents amount of each dollar spent on textbooks that goes to college store operations p. 351 |

How has the digital turn changed media distribution? p. 187 |

|

THE TRANSITION FROM WIRED TO WIRELESS HAPPENED FIRST IN RADIO p. 152 |

|

Microsoft

Microsoft, the oldest of the dominant digital firms (established by Bill Gates and Paul Allen in 1975), is an enormously wealthy software company that struggled for years to develop an Internet strategy. Although its software business is in a gradual decline, its flourishing digital game business (Xbox) helped it to continue to innovate and find a different path to a future in digital media. The company finally found moderate success on the Internet with its search engine Bing. With the 2012 release of the Windows Phone 8 mobile operating system and the Surface tablet, Microsoft was prepared to offer a formidable challenge in the mobile media business. In 2014, Microsoft brought its venerable office software to mobile devices, with Office for iPad and Office Mobile for iPhones and Android phones, all of which work with OneDrive, Microsoft’s cloud service.

Google, established in 1998, had instant success with its algorithmic search engine and now controls about 70 percent of the search market, generating billions of dollars of revenue yearly through the pay-

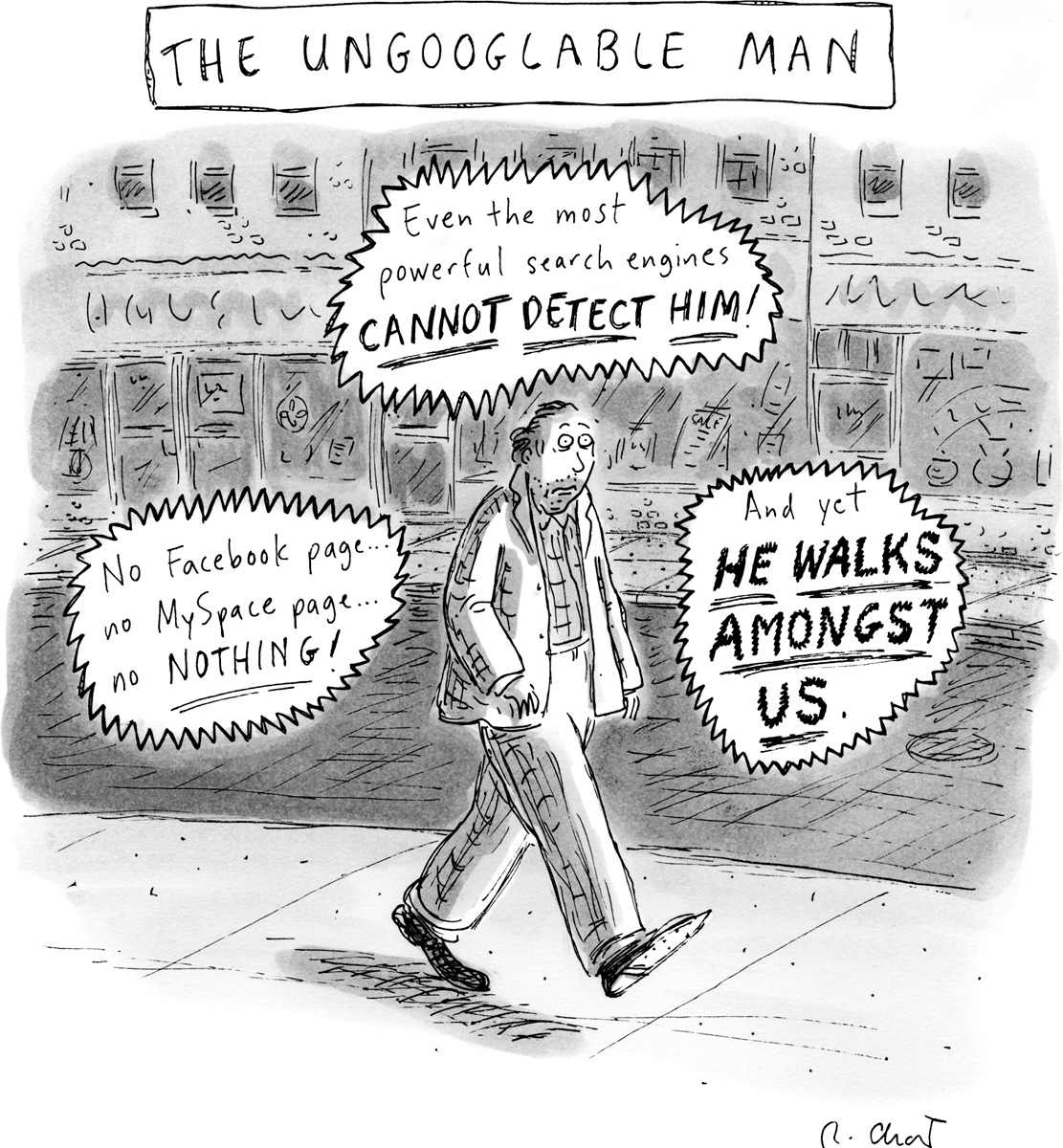

As the Internet goes wireless, Google has acquired other companies in its quest to replicate its online success in the wireless world. Beginning in 2005, Google bought the Android operating system (now the leading mobile phone platform, and also a tablet computer platform) and mobile phone ad placement company AdMob. Google continues to experiment with new devices, such as Google Glass, which layers virtual information over one’s real view of the world through eyeglasses, and Android Wear, its new line of wearable technology (the first product is a smartwatch). Google’s biggest challenge is the “closed Web”: companies like Facebook and Apple that steer users to online experiences that are walled off from search engines and threaten Google’s reign as the Internet’s biggest advertising conglomerate.

Apple

Apple, Inc., was founded by Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak in 1976 as a home computer company and is today the most valuable company in the world (by 2014, Google was the second most valuable company, ExxonMobil was third, and Microsoft was fourth).24 Apple was only moderately successful until 2001, when Jobs, having been forced out of the company for a decade, returned. Apple introduced the iPod and iTunes in 2003, two innovations that led the company to become the No. 1 music retailer in the United States. Then in 2007, Jobs introduced the iPhone, transforming the mobile phone industry. With Apple’s release of the intensely anticipated iPad in 2010, the company further redefined portable computing.

With the iPhone and iPad now at the core of Apple’s business, the company expanded to include providing content—

Amazon

Amazon started its business in 1995 in Seattle, selling the world’s oldest mass medium (books) online. Since that time, Amazon has developed into the world’s largest e-

Facebook’s immense, socially dynamic audience (about two-

As a young company, Facebook has suffered growing pains while trying to balance its corporate interests (capitalizing on its millions of users) with its users’ interest in controlling the privacy of their own information. In 2012, Facebook had the third-

Targeted Advertising and Data Mining

In the early years of the Web, advertising took the form of traditional display ads placed on pages. The display ads were no more effective than newspaper or magazine advertisements, and because they reached small, general audiences, they weren’t very profitable. But in the late 1990s, Web advertising began to shift to search engines. Paid links appeared as “sponsored links” at the top, bottom, and side of a search engine result list and even, depending on the search engine, within the “objective” result list itself. Every time a user clicks on a sponsored link, the advertiser pays the search engine for the click-

Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram in 2012 aided the social networking site’s future as a provider of mobile interfaces. Yet Facebook is preparing for the possibility that its social network’s popularity may fade. In 2014, Facebook paid $19 billion for WhatsApp, a cross-

Advertising has since spread to other parts of the Internet, including social networking sites, e-

Gathering users’ location and purchasing habits has been a boon for advertising, but these data-

One common method that commercial interests use to track the browsing habits of computer users is cookies, or information profiles that are automatically collected and transferred between computer servers whenever users access Web sites.28 The legitimate purpose of a cookie is to verify that a user has been cleared for access to a particular Web site, such as a library database that is open only to university faculty and students. However, cookies can also be used to create marketing profiles of Web users to target them for advertising. Many Web sites require the user to accept cookies in order to gain access to the site.

Even more unethical and intrusive is spyware, information-

In 1998, the FTC developed fair information practice principles for online privacy to address the unauthorized collection of personal data. These principles require Web sites to (1) disclose their data-

GLOBAL VILLAGE

Designed in California, Assembled in China

There is a now-

On its sleek packaging, Apple proudly proclaims that its products are “Designed by Apple in California,” a slogan that evokes beaches, sunshine, and Silicon Valley—

It wasn’t until 2012 that most Apple customers learned that China’s Foxconn was the company where their devices are assembled. Investigative reports by the New York Times revealed a company with ongoing problems with labor conditions and worker safety, including fatal explosions and a spate of worker suicides.2 (Foxconn responded in part by erecting nets around its buildings to prevent fatal jumps.)

Foxconn (also known as Hon Hai Precision Industry Co., Ltd., with headquarters in Taiwan) is China’s largest and most prominent private employer, with 1.2 million employees—

Behind this manufacturing might is a network of factories now legendary for its enormity. Foxconn’s largest factory compound is in Shenzhen. Dubbed “Factory City,” it employs roughly 300,000 people—

Conditions at Foxconn might, in some ways, be better than the conditions in the poverty-

In light of the news reports about the problems at Foxconn, Apple joined the Fair Labor Association (FLA), an international nonprofit that monitors labor conditions. The FLA inspected factories and surveyed more than thirty-

In 2014, Apple reported that its supplier responsibility program had resulted in improved labor conditions at supplier factories. But Apple might not have taken any steps had it not been for the New York Times investigative reports and the intense public scrutiny that followed. What is our role as consumers in ensuring that Apple and other companies are ethical and transparent in the treatment of the workers who make our electronic devices?

Media Literacy and the Critical Process

Tracking and Recording Your Every Move

Imagine if you went into a department store and someone followed you the whole time, noting every place you stopped to look at something and recording every item you purchased. Then imagine that the same person followed you the same way on every return visit. It’s likely that you would be outraged by such surveillance. Now imagine that the same thing happens when you search the Web—

1 DESCRIPTION. Do an audit of your Web browser’s data collection—

2 ANALYSIS. From your five minutes of browsing five Web sites, look for patterns in the cookies. How many total were there? Which types of sites had multiple cookies? Sample ten to twenty cookies for a close-

3 INTERPRETATION. Why are our searches tracked with cookies and our search histories recorded? Is this done solely for the convenience of advertisers, marketers, and Google, which mine our search data for commercial purposes, or is there value to you in this? (Firefox is owned by a nonprofit, the Mozilla Foundation.)1

4 EVALUATION. Web sites don’t tell you they are installing cookies on your computer. Cookies and search histories can be found and deleted, but do the browsers make this easy or difficult for you? Did you know this information was being collected? Should you have more say in the data being collected on your searches? Overall, should Web sites be more transparent and honest about what they do in placing cookies and their purpose? Should Web browsers be more transparent and honest about the cookies and histories they save and whether they are used for data mining?

5 ENGAGEMENT. What can you do to preserve your privacy? On a personal level, start by clearing out your cookies and search history after every session. On Firefox (under Privacy), you can check “Tell sites that I do not want to be tracked.” On Chrome, you can select Clear Browsing Data in the main menu. Alternatively, Chrome offers “incognito mode” for browsing, with the following warning: “You’ve gone incognito. Pages you view in incognito tabs won’t stick around in your browser’s history, cookie store, or search history after you’ve closed all of your incognito tabs. Any files you download or bookmarks you create will be kept. Going incognito doesn’t hide your browsing from your employer, your internet service provider, or the websites you visit.” For greater privacy, you can use the search engine DuckDuckGo (launched in 2008), which doesn’t track your searches or put them in a “filter bubble” (that is, it doesn’t filter search results based on what the search engine knows about your previous searches, which is what Google does). On a social level, you can file a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission. Go to www.ftccomplaintassistant.gov, but be aware that even the FTC may use cookies to process your complaint.

Security: The Challenge to Keep Personal Information Private

When you watch television, listen to the radio, read a book, or go to the movies, you do not need to provide personal information to others. However, when you use the Internet, whether you are signing up for an e-

Government Surveillance

Since the inception of the Internet, government agencies worldwide have obtained communication logs, Web browser histories, and the online records of individual users who thought their online activities were private. In the United States, for example, the USA PATRIOT Act (which became law about a month after the September 11 attacks in 2001 and was renewed in 2006) grants sweeping powers to law-

Online Fraud

In addition to being an avenue for surveillance, the Internet is increasingly a conduit for online robbery and identity theft, the illegal obtaining of personal credit and identity information in order to fraudulently spend other people’s money. Computer hackers have the ability to infiltrate Internet databases (from banks to hospitals to even the Pentagon) to obtain personal information and to steal credit card numbers from online retailers. Identity theft victimizes hundreds of thousands of people a year, and clearing one’s name can take a very long time and cost a lot of money. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, about 7 percent of Americans were victims of identity theft in 2012, totaling about $24.7 billion in losses.30 One particularly costly form of Internet identity theft is known as phishing. This scam involves phony e-

Appropriateness: What Should Be Online?

The question of what constitutes appropriate content has been part of the story of most mass media, from debates over the morality of lurid pulp-

As has always been the case, eliminating some forms of sexual content from books, films, television, and other media remains a top priority for many politicians and public interest groups. So it should not be surprising that public objection to indecent and obscene Internet content has led to various legislative efforts to tame the Web. Although the Communications Decency Act of 1996 and the Child Online Protection Act of 1998 were both judged unconstitutional, the Children’s Internet Protection Act of 2000 was passed and upheld in 2003. This act requires schools and libraries that receive federal funding for Internet access to use software that filters out any visual content deemed obscene, pornographic, or harmful to minors, unless disabled at the request of adult users. Regardless of new laws, pornography continues to flourish on commercial sites, individuals’ blogs, and social networking pages. As the American Library Association notes, there is “no filtering technology that will block out all illegal content, but allow access to constitutionally protected materials.”31

Although the “back alleys of sex” on the Internet have caused considerable public concern, Internet sites that carry potentially dangerous information (bomb-

Access: The Fight to Prevent a Digital Divide

A key economic issue related to the Internet is whether the cost of purchasing a personal computer and paying for Internet services will undermine equal access. Coined to echo the term economic divide (the disparity of wealth between the rich and the poor), the term digital divide refers to the growing contrast between the “information haves,” those who can afford to purchase computers and pay for Internet services, and the “information have-

Although about 87 percent of U.S. households are connected to the Internet, there are big gaps in access. For example, a 2014 study found that only 57 percent of Americans age sixty-

The rising use of smartphones is helping to narrow the digital divide, particularly along racial lines. In the United States, African American and Hispanic families have generally lagged behind whites in home access to the Internet, which requires a computer and broadband access. However, the Pew Internet & American Life Project reported that African Americans and Hispanics are active users of mobile Internet devices. The report concluded, “While blacks and Latinos are less likely to have access to home broadband than whites, their use of smartphones nearly eliminates that difference.”33

Globally, though, the have-

Even as the Internet matures and becomes more accessible, wealthy users are still more able to buy higher levels of privacy and faster speeds of Internet access than are other users. Whereas traditional media made the same information available to everyone who owned a radio or a TV set, the Internet creates economic tiers and classes of service. Policy groups, media critics, and concerned citizens continue to debate the implications of the digital divide, valuing the equal opportunity to acquire knowledge.

Net Neutrality: Maintaining an Open Internet

LaunchPad

Net Neutrality

Experts discuss net neutrality and privatization of the Internet.

Discussion: Do you support net neutrality? Why or why not?

For more than a decade, the debate over net neutrality has framed the shape of the Internet’s future. Net neutrality refers to the principle that every Web site and every user—

The dispute over net neutrality and the future of the Internet is dominated by some of the biggest communications corporations. These major telephone and cable companies—

Supporters of net neutrality—

In late 2010, the FCC adopted rules on net neutrality, noting that “the Internet’s openness promotes innovation, investment, competition, free expression, and other national broadband goals.”36 But the FCC’s rules were twice rejected by federal courts, most recently in 2014. Afterward, FCC chairman Tom Wheeler proposed that the FCC’s new policy on the Internet would allow cable and telephone companies to charge tiered fees for slow and fast service. The New York Times argued that if the policy is approved, it would create “a two-

Alternative Voices

Independent programmers continue to invent new ways to use the Internet and communicate over it. While some of their innovations have remained free of corporate control, others have been taken over by commercial interests. Despite commercial buyouts, however, the pioneering spirit of the Internet’s independent early days endures; the Internet continues to be a participatory medium in which anyone can be involved. Two of the most prominent areas in which alternative voices continue to flourish relate to open-

Open-

In the early days of computer code writing, amateur programmers were developing open-

However, programmers are still developing noncommercial, open-

Digital Archiving

Librarians have worked tirelessly to build nonprofit digital archives that exist outside of any commercial system in order to preserve libraries’ tradition of open access to information. One of the biggest and most impressive digital preservation initiatives is the Internet Archive, established in 1996. The Internet Archive aims to ensure that researchers, historians, scholars, and all citizens have universal access to human knowledge—

Media activist David Bollier has likened open-