The Media Playground

To fully explore the larger media playground, we need to look beyond electronic gaming’s technical aspects and consider the human faces of gaming. The attractions of this interactive playground validate electronic gaming’s status as one of today’s most powerful social media. Electronic games occupy an enormous range of styles, from casual games like Tetris, Angry Birds, Bejeweled, and Fruit Ninja—described by one writer as “stupid games” that are typically “a repetitive, storyless puzzle that could be picked up, with no loss of potency, at any moment, in any situation”—to full-

Video Game Genres

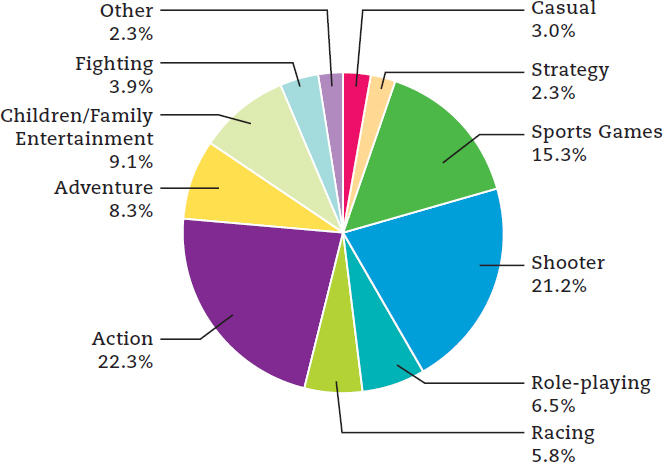

Electronic games inhabit so many playing platforms and devices, and cover so many genres, that they are not easy to categorize. The game industry, as represented by the Entertainment Software Association, organizes games by gameplay—the way in which the rules structure how players interact with the game—

CASE STUDY

Watch Dogs Hacks Our Surveillance Society

by Olivia Mossman

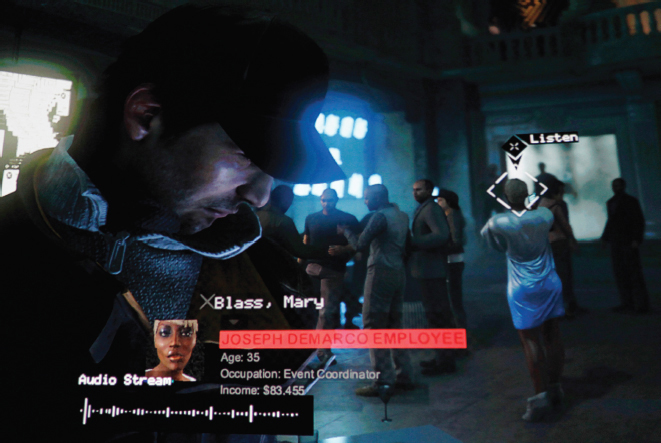

With the revelations of government surveillance brought to light by WikiLeaks and Edward Snowden, many Americans are now aware of the possibility that their phone calls are being overheard, their Internet searches observed, and other surveillance conducted without their permission. But what if individual American citizens had the same kind of almost-

A new open-

The Aiden character uses hacking, government records, and surveillance to track down the killer of his niece. However, the game eerily puts into perspective a “futuristic,” technologically connected world that looks even more similar to current society than the game designers planned. Players will see a Chicago that is heavily monitored by technology, and while some of the game still uses fantastical versions of smart systems, Watch Dogs also predicts where society is headed. In fact, when game developers began constructing the video game in 2009, smartphones were only just emerging. Now they are Aiden’s primary weapon and a keystone of society. In reality, the interconnectivity of Chicago is not far from the vision of Watch Dogs. A report by video gaming Web site Polygon explains how Chicago’s surveillance systems are primarily used for fighting crime but have increased in number, decreased in size, and infiltrated the city, even using facial recognition to assist in catching culprits.2 As Aiden, players can access people’s history, identity, and personal accounts for their own self-

Watch Dogs offers another element that is more fact than fiction: It requires users to use game information to make moral decisions. As the game promo says, when playing as Aiden Pearce, you “use your hacking abilities for good or bad—

With this context, killing or hacking game characters with names, faces, and stories is not as easy as it is in other games. Would players hack into the Webcam of a rich woman, who had recently lost her daughter, and then steal money from her bank account to line their own character’s pockets? To avoid getting arrested in a car chase, would players knowingly run over a civilian who is a tobacco executive but also volunteers his time and money at homeless shelters? The game makes players question what truly matters, which evils are “worse,” and whether they would sacrifice themselves for others. Even the multiplayer version of the game allows players to hack into another real player’s game, giving them the option to “kill” a real player’s character. In Watch Dogs, players determine their own morality and act on it—

Olivia Mossman is a game player, a writer, and a communication studies student at the University of Northern Iowa.

Action and Shooter Games

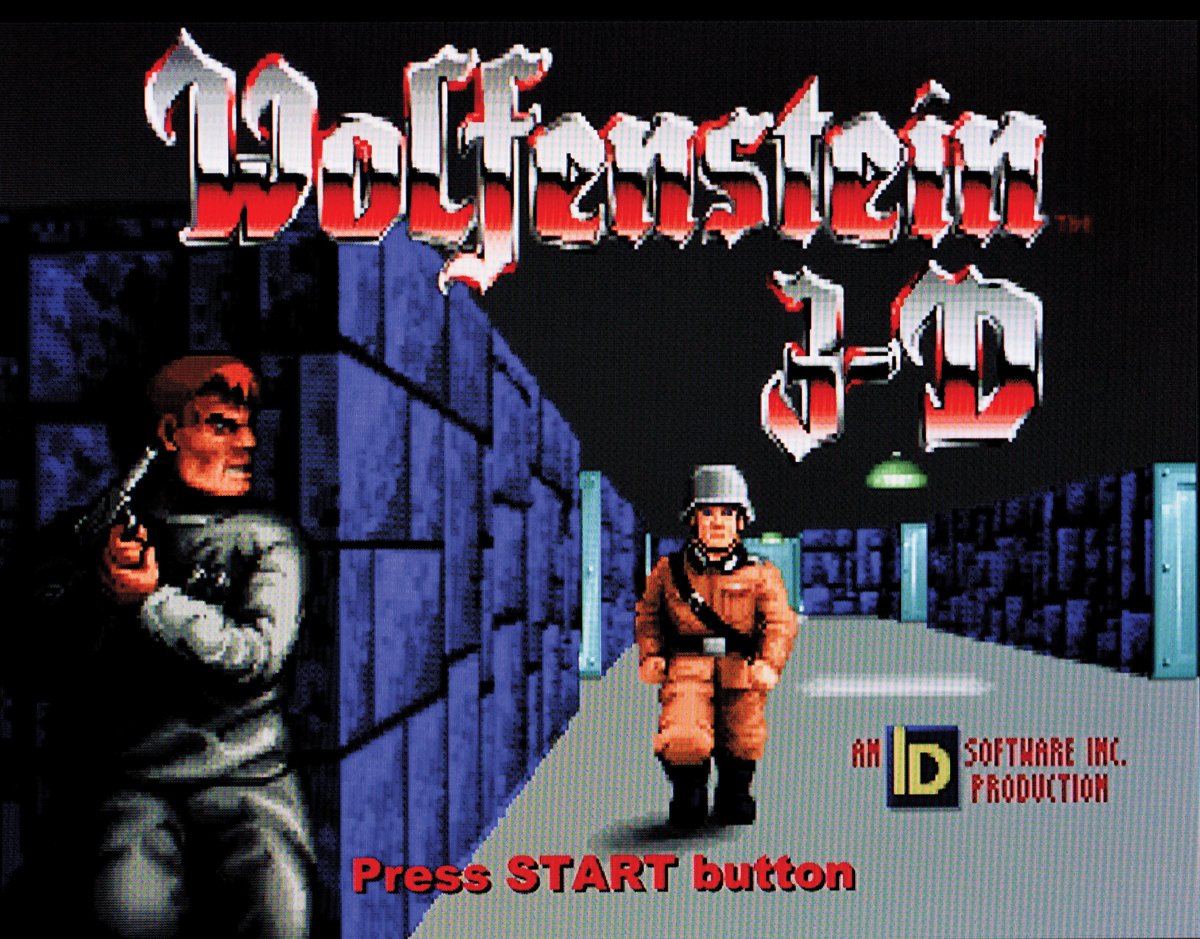

Usually emphasizing combat-

Most shooter games have a first-

| Convention | Description | Examples | Visual Representation |

| Avatars | Onscreen figures of player identification | Pac- |

|

| Bosses | Powerful enemy characters that represent the final challenge in a stage or the entire game | Ganon from the Zelda series, Hitler in Castle Wolfenstein, Dr. Eggman from Sonic the Hedgehog, Mother Brain from Metroid |

|

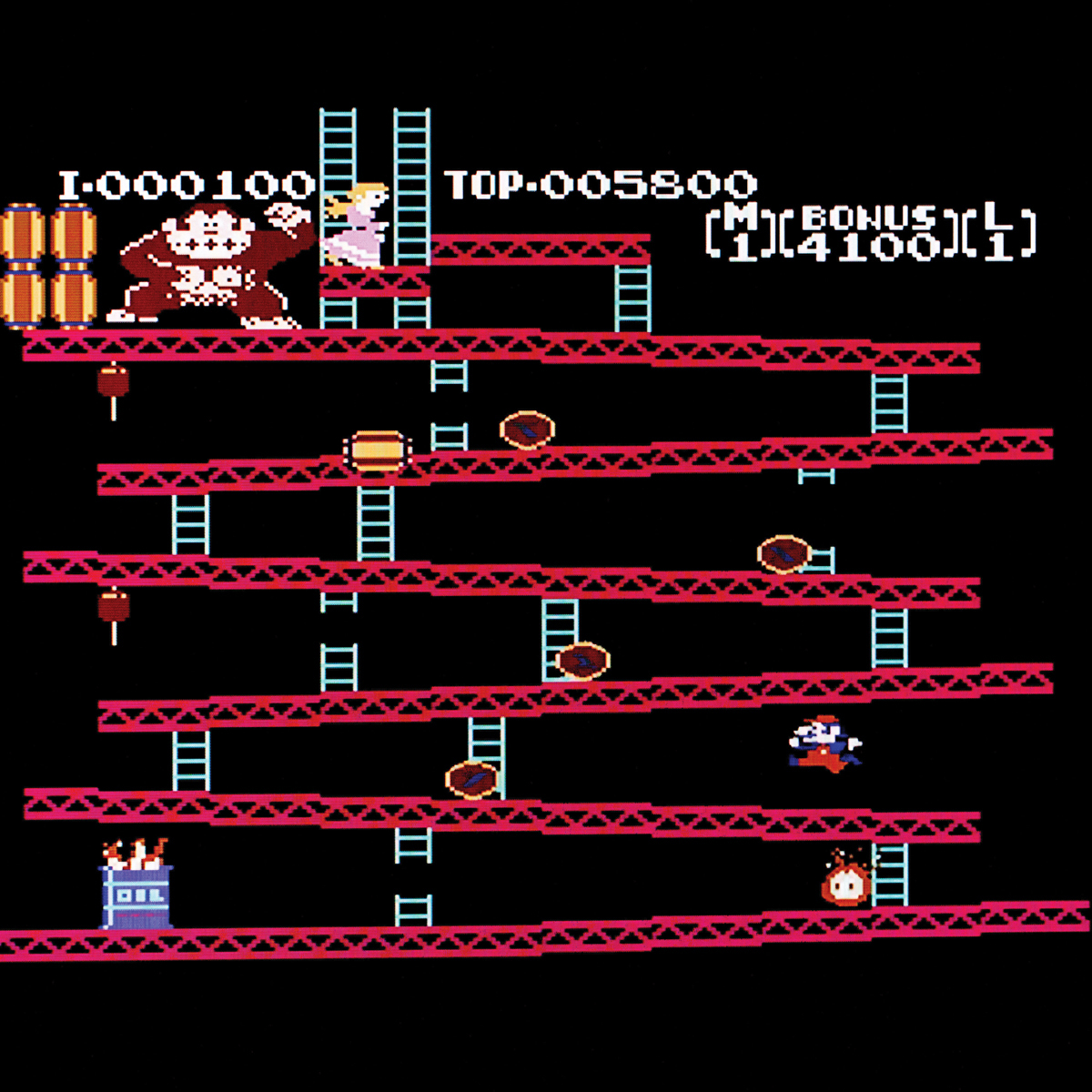

| Vertical and Side Scrolling | As opposed to a fixed screen, scrolling that follows the action as it moves up, down, or sideways in what is called a “tracking shot” in the cinema | Platform games like Jump Bug, Donkey Kong, and Super Mario Bros.; also integrated into the design of Angry Birds |

|

|

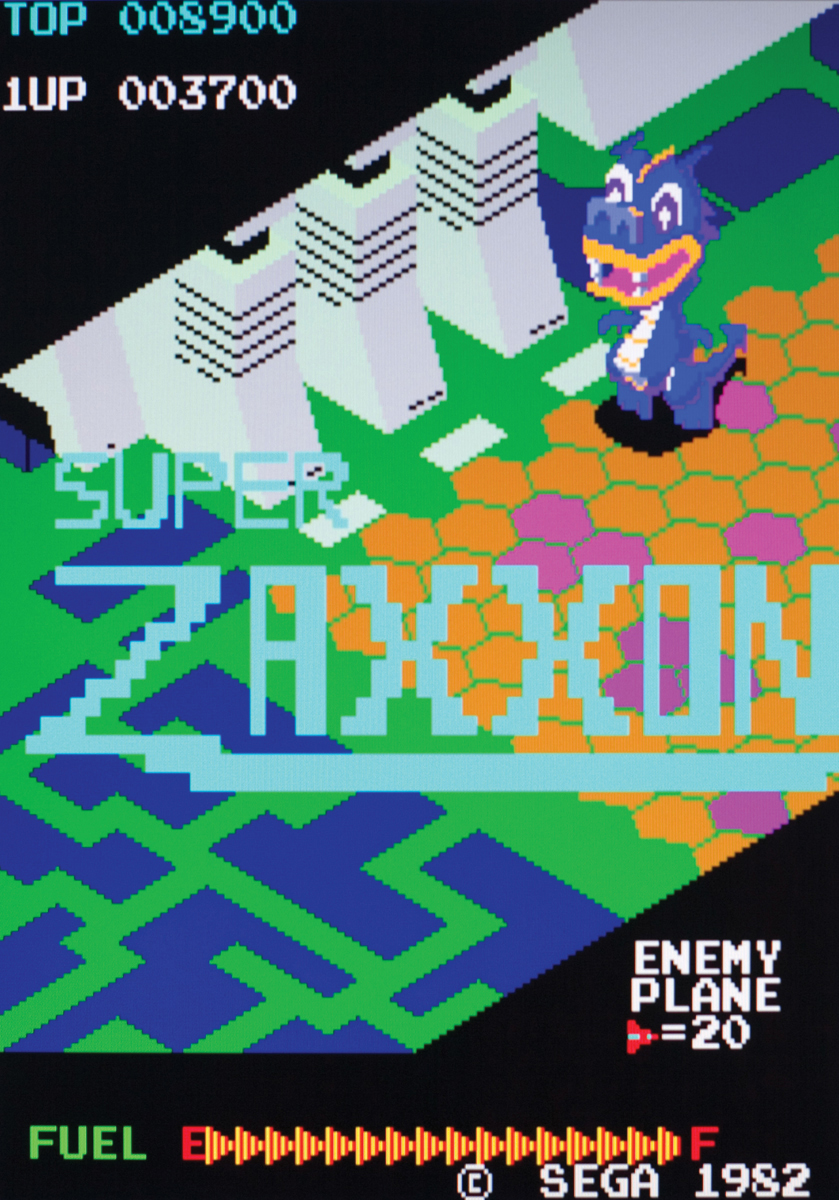

Isometric Perspective(or Three- |

An elevated and angled perspective that enhances the sense of three- |

Zaxxon, StarCraft, Civilization, and Populous |

|

| First- |

Presents the gameplay through the eyes of your avatar | First- |

|

|

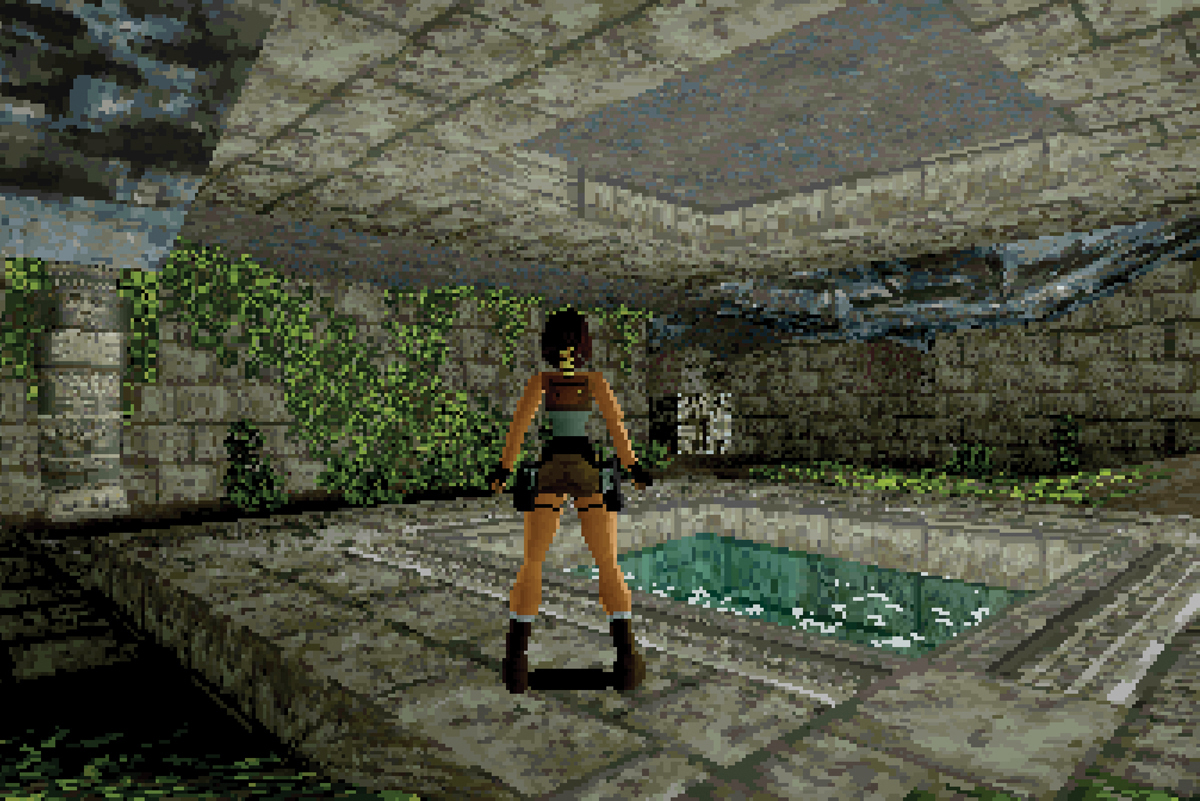

Third- |

Enables you to view your heroic avatar in action from an external viewpoint | Tomb Raider, Assassin’s Creed, and the default viewpoint in World of Warcraft |

|

Maze games like Pac-

Adventure Games

Developed in the 1970s, adventure games involve a type of gameplay that is in many ways the opposite of action games. Typically nonconfrontational in nature, adventure games such as Myst require players to interact with individual characters and the sometimes-

Role-

Role-

Strategy and Simulation Games

Strategy video games often involve military battles (real or imaginary) and focus on gameplay that requires careful thinking and skillful planning in order to achieve victory. Unlike FPS games, the perspective in strategy games is omniscient, with the player surveying the entire “world,” or playing field, and making strategic decisions—

Like strategy games, simulation games involve managing resources and planning worlds, but these worlds are typically based in reality. A good example is SimCity, which asks players to build a city given real-

Casual Games

This category of gaming, which encompasses everything from Minesweeper to Angry Birds to Words with Friends, includes games that have very simple rules and are usually quick to play. The historical starting point of casual games was 1989, when the game Tetris came bundled with every new Game Boy (Nintendo). Tetris requires players to continuously (frantically, for some) rotate colored blocks and fit them into snug spaces before the screen fills up with badly stacked blocks. There is no story to Tetris, and no real challenge other than mastering the rather numbing pattern of rotating and stacking, a process that keeps getting faster as the player achieves higher levels. For many people, the ceaseless puzzle is like a drug: Millions of people have purchased and played Tetris since its release. Today, Tetris has given way to Angry Birds, Candy Crush Saga, and other such games that have exploded in popularity due in large part to the rise in mobile devices.

Sports, Music, and Dance Games

“There is apparently a video game for every sport except for competitive mushroom picking,” commented a Milwaukee Journal editorial in 1981.17 Today, there really does seem to be a game for every sport. Gaming consoles first featured 3-

One of the most consistently best-

Other experiential games tie into music and dance categories. Rock Band, developed by Harmonix Systems and published by Mad Catz, allows up to four players to simulate the popular rock band performances of fifty-

Communities of Play: Inside the Game

Virtual communities often crop up around online video games and fantasy sports leagues. Indeed, players may get to know one another through games without ever meeting in person. They can interact in two basic types of groups. PUGs (short for “pick-

Because of the frustration of dealing with noobs, ninjas, and trolls, most experienced players join organized groups called guilds or clans. These groups can be small and easygoing or large and demanding. Guild members can usually avoid PUGs and team up with guildmates to complete difficult challenges requiring coordinated group activity. As the terms ninja, troll, and noob suggest, online communication is often encoded in gamespeak, a language filled with jargon, abbreviations, and acronyms relevant to gameplay. The typical codes of text messaging (OMG, LOL, ROFL, and so forth) form the bedrock of this language system.

Players communicate in two forms of in-

Communities of Play: Outside the Game

Communities also form outside games, through Web sites and even face-

Collective Intelligence

Mass media productions are almost always collaborative efforts, as is evident in the credits for movies, television shows, and music recordings. The same goes for digital games. But what is unusual about game developers and the game industry is their interest in listening to gamers and their communities in order to gather new ideas and constructive criticism and to gauge popularity. Gamers, too, collaborate with one another to share shortcuts and “cheats” to solving tasks and quests, and to create their own modifications to games. This sharing of knowledge and ideas is an excellent example of collective intelligence. French professor Pierre Lévy coined the term collective intelligence in 1997 to describe the Internet, “this new dimension of communication,” and its ability to “enable us to share our knowledge and acknowledge it to others.”18 In the world of gaming, where users are active participants (more than in any other medium), the collective intelligence of players informs the entire game environment.

For example, collective intelligence (and action) is necessary to work through levels of many games. In World of Warcraft, collective intelligence is highly recommended. According to the beginner’s guide, “If you want to take on the greatest challenges World of Warcraft has to offer, you will need allies to fight by your side against the tides of darkness.”19 Players form guilds and use their play experience and characters’ skills to complete quests and move to higher levels. Gamers also share ideas through chats and wikis, and those looking for tips and cheats provided by fellow players need only Google what they want. The largest of the sites devoted to sharing collective intelligence is the World of Warcraft wiki (www.wowwiki.com). Similar user-

The most advanced form of collective intelligence in gaming is modding, slang for “modifying game software or hardware.” In many mass communication industries, modifying hardware or content would land someone in a copyright lawsuit. In gaming, modding is often encouraged, as it is yet another way players become more deeply invested in a game, and it can improve the game for others. For example, Counter-

Game Sites

Game sites and blogs are among the most popular external communities for gamers. IGN (owned by Ziff Davis), GameSpot (owned by CBS), GameTrailers (MTV Networks/Viacom), and Kotaku (Gawker Media) are four of the leading Web sites for gaming. GameSpot and IGN are apt examples of giant industry sites, each with sixteen to nineteen million unique, mostly male, eighteen-

Conventions

In addition to online gaming communities, there are conventions and expos where video game enthusiasts can come together in person to test out new games and other new products, play old games in competition, and meet video game developers. One of the most significant is the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3), which draws more than 45,000 industry professionals, investors, developers, and retailers to its annual meeting. E3 is the place where the biggest new game titles and products are unveiled, and it is covered by hundreds of journalists, televised on Spike TV, and streamed to mobile devices and Xbox consoles.

The Penny Arcade Expo (PAX) is a convention created by gamers for gamers, held each year in Seattle and Boston. One of its main attractions is the Omegathon, a three-