Radio Reinvents Itself

Older media forms do not generally disappear when confronted by newer forms. Instead, they adapt. Although radio threatened sound recording in the 1920s, the recording industry adjusted to the economic and social challenges posed by radio’s arrival. Remarkably, the arrival of television in the 1950s marked the only time in media history when a new medium stole virtually every national programming and advertising strategy from an older medium. Television snatched radio’s advertisers, program genres, major celebrities, and large evening audiences. The TV set even physically displaced the radio as the living room centerpiece of choice across America. Nevertheless, radio adapted and continued to reach an audience.

The story of radio’s evolution and survival is especially important today, as newspapers and magazines appear online and as publishers produce e-

Transistors Make Radio Portable

A key development in radio’s adaptation to television occurred with the invention of the transistor by Bell Laboratories in 1947. Transistors were small electrical devices that, like vacuum tubes, could receive and amplify radio signals. However, they used less power and produced less heat than vacuum tubes, and they were more durable and less expensive. Best of all, they were tiny. Transistors, which also revolutionized hearing aids, constituted the first step in replacing bulky and delicate tubes, leading eventually to today’s integrated circuits.

Texas Instruments marketed the first transistor radio in 1953 for about $40. Using even smaller transistors, Sony introduced the pocket radio in 1957. But it wasn’t until the 1960s that transistor radios became cheaper than conventional tube and battery radios. For a while, the term transistor became a synonym for a small, portable radio.

The development of transistors let radio go where television could not—

The FM Revolution and Edwin Armstrong

By the time the broadcast industry launched commercial television in the 1950s, many people, including David Sarnoff of RCA, were predicting radio’s demise. To fund television’s development and to protect his radio holdings, Sarnoff had even delayed a dramatic breakthrough in broadcast sound, what he himself called a “revolution”—FM radio.

Edwin Armstrong, who first discovered and developed FM radio in the 1920s and early 1930s, is often considered the most prolific and influential inventor in radio history. He used De Forest’s vacuum tube to invent an amplifying system that enabled radio receivers to pick up distant signals, rendering the enormous alternators used for generating power in early radio transmitters obsolete. In 1922, he sold a “super” version of his circuit to RCA for $200,000 and sixty thousand shares of RCA stock, which made him a millionaire as well as RCA’s largest private stockholder.

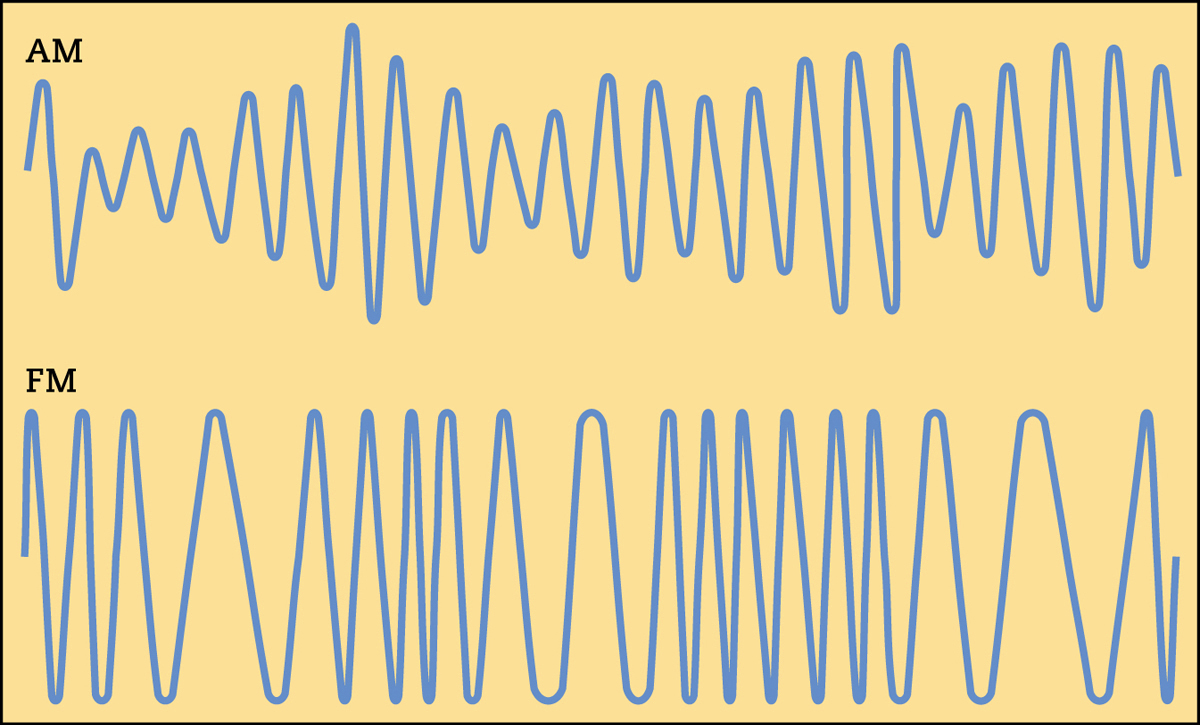

Armstrong also worked on the major problem of radio reception—

Although David Sarnoff, RCA’s president, thought that television would replace radio, he helped Armstrong set up the first experimental FM station atop the Empire State Building in New York City. Eventually, though, Sarnoff thwarted FM’s development (which he was able to do because RCA had an option on Armstrong’s new patents). Instead, in 1935 Sarnoff threw RCA’s considerable weight behind the development of television. With the FCC allocating and reassigning scarce frequency spaces, RCA wanted to ensure that channels went to television before they went to FM. But most of all, Sarnoff wanted to protect RCA’s existing AM empire. Given the high costs of converting to FM and the revenue needed for TV experiments, Sarnoff decided to close down Armstrong’s station.

Armstrong forged ahead without RCA. He founded a new FM station and advised other engineers, who started more than twenty experimental stations between 1935 and the early 1940s. In 1941, the FCC approved limited space allocations for commercial FM licenses. During the next few years, FM grew in fits and starts. Between 1946 and early 1949, the number of commercial FM stations expanded from 48 to 700. But then the FCC moved FM’s frequency space to a new band on the electromagnetic spectrum, rendering some 400,000 prewar FM receiver sets useless. FM’s future became uncertain, and by 1954, the number of FM stations had fallen to 560.

On January 31, 1954, Edwin Armstrong—

Although AM stations had greater reach, they could not match the crisp fidelity of FM, which made FM preferable for music. In the early 1970s, about 70 percent of listeners tuned almost exclusively to AM radio. By the 1980s, however, FM had surpassed AM in profitability. By the 2010s, more than 75 percent of all listeners preferred FM, and about 6,660 commercial and about 4,000 educational FM stations were in operation. The expansion of FM represented one of the chief ways radio survived television and Sarnoff’s gloomy predictions.

The Rise of Format and Top 40 Radio

Live and recorded music had long been radio’s single biggest staple, accounting for 48 percent of all programming in 1938. Although live music on radio was generally considered superior to recorded music, early disc jockeys made a significant contribution to the latter, demonstrating that music alone could drive radio. In fact, when television snatched radio’s program ideas and national sponsors, radio’s dependence on recorded music became a necessity and helped the medium survive the 1950s.

As early as 1949, station owner Todd Storz in Omaha, Nebraska, experimented with formula-

As format radio grew, program directors combined rapid deejay chatter with the best-

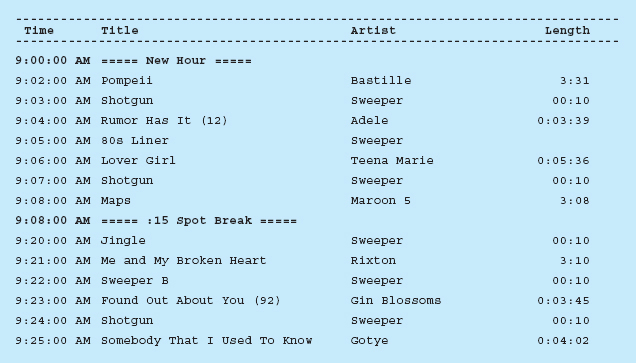

In format radio, management carefully coordinates, or programs, each hour, dictating what the deejay will do at various intervals throughout each hour of the day (see Figure 5.3). Management creates a program log—

Radio managers further sectioned off programming into day parts, which typically consisted of time blocks covering 6 to 10 A.M., 10 A.M. to 3 P.M., 3 to 7 P.M., and 7 P.M. to midnight. Each day part, or block, was programmed through ratings research according to who was listening. For instance, a Top 40 station would feature its top deejays in the morning and afternoon periods when audiences, many riding in cars, were largest. From 10 A.M. to 3 P.M., research determined that women at home and secretaries at work usually controlled the dial, so program managers, capitalizing on the gender stereotypes of the day, played more romantic ballads and less hard rock. Teenagers tended to be heavy evening listeners, so program managers often discarded news breaks at this time, since research showed that teens turned the dial when news came on.

Critics of format radio argued that only the top songs received play and that lesser-

Resisting the Top 40

The expansion of FM in the mid-

Experimental FM stations, both commercial and noncommercial, offered a cultural space for hard-