The Development of Cable

Most historians mark the period from the late 1950s, when the networks gained control over TV’s content, to the end of the 1970s as the network era. Except for British and American anthology dramas on PBS, this was a time when the Big Three broadcast networks—

CATV—

The first small cable systems—

In the beginning, small communities with CATV often received twice as many channels as were available over the air in much larger cities. That technological advantage, combined with cable’s ability to deliver clear reception, would soon propel the new cable industry into competition with conventional broadcast television. But unlike radio, which freed mass communication from unwieldy wires, early cable technology relied on wires.

The Wires and Satellites behind Cable Television

The idea of using space satellites to receive and transmit communication signals is right out of science fiction: In 1945, Arthur C. Clarke (who studied physics and mathematics and would later write dozens of sci-

In 1960, AT&T launched Telstar, the first communication satellite capable of receiving, amplifying, and returning signals. Telstar was able to process and relay telephone and occasional television signals between the United States and Europe. By the mid-

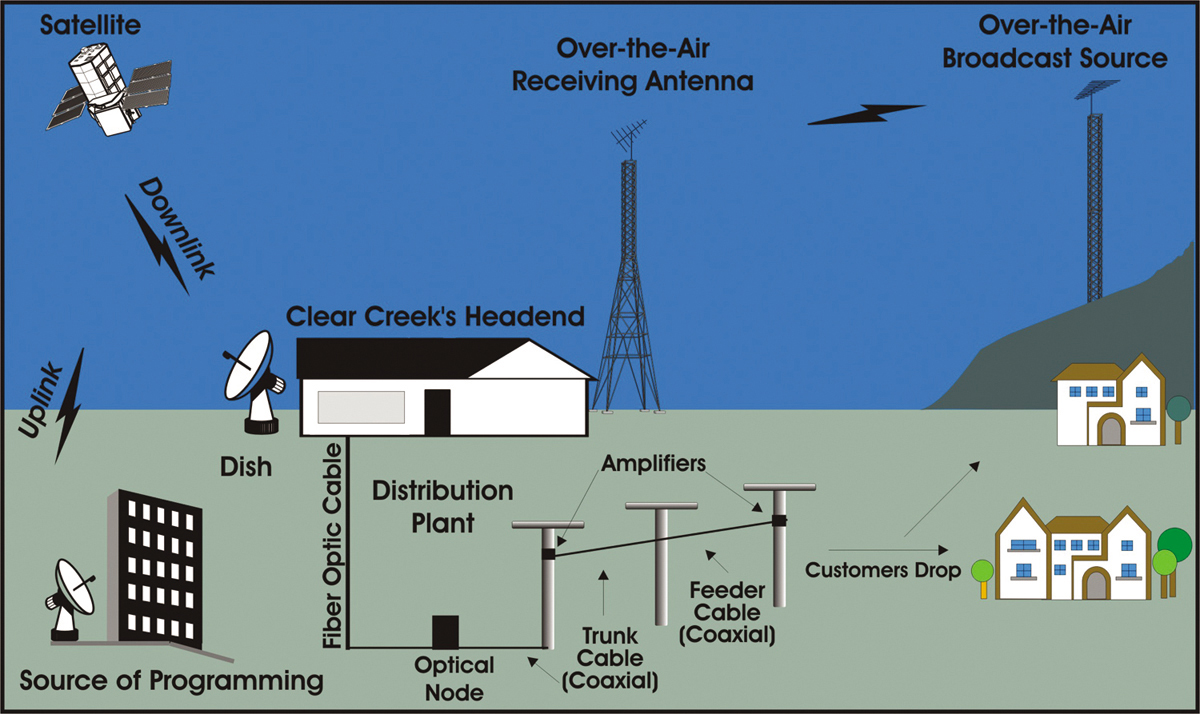

Cable TV signals are processed at a computerized nerve center, or headend, which operates various large satellite dishes that receive and distribute long-

Advances in satellite technology in the 1970s dramatically changed the fortunes of cable by creating a reliable system for the distribution of programming to cable companies across the nation. The first cable network to use satellites for regular transmission of TV programming was Home Box Office (HBO), which began delivering programming such as uncut, commercial-

Cable Threatens Broadcasting

While only 14 percent of all U.S. homes received cable in 1977, by 1985 that percentage had climbed to 46. By the summer of 1997, basic cable channels had captured a larger prime-

As cable channels have become more and more like specialized magazines or radio formats, they have siphoned off network viewers, and the networks’ role as the chief programmer of our shared culture has eroded. For example, back in 1980, the Big Three evening news programs had a combined audience of more than fifty million on a typical weekday evening. By 2012 and 2013, though, that audience had shrunk to twenty million.1 In addition, through its greater channel capacity, cable has provided more access. In many communities, various public, government, and educational channels have made it possible for anyone to air a point of view or produce a TV program. When it has lived up to its potential, cable has offered the public opportunities to participate more fully in the democratic promise of television.

Cable Services

Cable consumers usually choose programming from a two-

Basic Cable Services

A typical basic cable system today includes a hundred-

Premium Cable Services

Besides basic programming, cable offers a wide range of special channels, known as premium channels, which lure customers with the promise of no advertising; recent and classic Hollywood movies; and original movies or series, like HBO’s Game of Thrones, True Detective, or Girls, and Showtime’s Homeland, Masters of Sex, or Penny Dreadful. These channels are a major source of revenue for cable companies: The cost to them is $4 to $6 per month per subscriber to carry a premium channel, but the cable company can charge customers $10 or more per month and reap a nice profit. Premium services also include pay-

Beginning in 1985, cable companies began introducing new viewing options for their customers. Pay-

CASE STUDY

ESPN: Sports and Stories

A common way many of us satisfy our cultural and personal need for storytelling is through sports: We form loyalties to local and national teams. We follow the exploits of favorite players. We boo our team’s rivals. We suffer with our team when the players have a bad game or an awful season. We celebrate the victories.

The appeal of sports is similar to the appeal of our favorite books, TV shows, and movies—

One of the best sports stories on television over the past thirty years, though, may be not a single sporting event but the tale of an upstart cable network based in Bristol, Connecticut. ESPN (Entertainment Sports Programming Network) began in 1979 and has now surpassed all the major broadcast networks as the “brand” that frames and presents sports on TV. In fact, cable operators around the country regard ESPN as the top service when it comes to helping them “gain and retain customers.”1 One of ESPN’s main attractions is its “live” aspect and its ability to draw large TV and cable audiences—

Today, the ESPN flagship channel reaches more than 100 million U.S. homes. And ESPN, Inc., now provides a sports smorgasbord—

Each year, ESPN’s channels air more than five thousand live and original hours of sports programming, covering more than sixty-

The story of ESPN’s birth also has its share of drama. The creator of ESPN was Bill Rasmussen, an out-

Today, ESPN is 80 percent owned by the Disney Company, while the Hearst Corporation holds the other 20 percent interest. The sports giant earned over $10 billion in worldwide revenue in 2012, and ESPN’s cable ad sales and higher subscription fees were major reasons why Disney’s sales revenue rose 8 percent in 2013, to more than $45 billion.

DBS: Cable without Wires

By 1999, cable penetration had hit 70 percent. But direct broadcast satellite (DBS) services presented a big challenge to cable—

Satellite service began in the mid-

Signal scrambling spawned companies that provided both receiving dishes and satellite program services for a monthly fee. In 1978, Japanese companies, which had been experimenting with “wireless cable” alternatives for years, started the first DBS system in Florida. By 1994, full-