Major Programming Trends

Television programming began by borrowing genres from radio, such as variety shows, sitcoms, soap operas, and newscasts. Starting in 1955, the Big Three networks gradually moved their entertainment divisions to Los Angeles because of its proximity to Hollywood production studios. Network news operations, however, remained in New York. Ever since, Los Angeles and New York came to represent the two major branches of TV programming: entertainment and information. Although there is considerable blurring between these categories today, the two were once more distinct. In the sections that follow, we focus on these long-

TV Entertainment: Our Comic Culture

The networks began to move their entertainment divisions to Los Angeles partly because of the success of the pioneering comedy series I Love Lucy (1951–

Sketch comedy, or short comedy skits, was a key element in early TV variety shows, which also included singers, dancers, acrobats, animal acts, stand-

However, the hour-

The situation comedy, or sitcom, features a recurring cast; each episode establishes a narrative situation, complicates it, develops increasing confusion among its characters, and then usually resolves the complications.10 I Love Lucy, Seinfeld, New Girl, The Big Bang Theory, and It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia are all examples of this genre.

In most sitcoms, character development is downplayed in favor of zany plots. Characters are usually static and predictable, and they generally do not develop much during the course of a series. Such characters “are never troubled in profound ways.” Stress, more often the result of external confusion rather than emotional anxiety, “is always funny.”11 Much like viewers of soap operas, sitcom fans feel just a little bit smarter than the characters, whose lives seem wacky and out of control. In some sitcoms (once referred to as “domestic comedies”), characters and settings are typically more important than complicated predicaments. Although an episode might offer a goofy situation as a subplot, the main narrative usually features a personal problem or family crisis that characters have to resolve. Greater emphasis is placed on character development than on reestablishing the order that has been disrupted by confusion. Such comedies take place primarily at home (Modern Family), at the workplace (Parks and Recreation), or at both (Curb Your Enthusiasm).

In TV history, some sitcoms of the domestic variety have mixed dramatic and comedic elements. This blurring of serious and comic themes marks a contemporary hybrid, sometimes labeled dramedy, which has included such series as The Wonder Years (1988–

TV Entertainment: Our Dramatic Culture

Because the production of TV entertainment was centered in New York City in its early days, many of its ideas, sets, technicians, actors, and directors came from New York theater. Young stage actors—

Anthology Drama and the Miniseries

In the early 1950s, television—

The anthology’s brief run as a dramatic staple on television ended for both economic and political reasons. First, advertisers disliked anthologies because they often presented stories containing complex human problems that were not easily resolved. The commercials that interrupted the drama, however, told upbeat stories in which problems were easily solved by purchasing a product; by contrast, anthologies made the simplicity of the commercial pitch ring false. A second reason for the demise of anthology dramas was a change in audience. The people who could afford TV sets in the early 1950s could also afford tickets to a play. For these viewers, the anthology drama was a welcome addition given their cultural tastes. By 1956, however, working-

Finally, anthologies that dealt seriously with the changing social landscape were sometimes labeled “politically controversial.” This was especially true during the attempts by Senator Joseph McCarthy and his followers to rid media industries and government agencies of left-

In fact, these British shows resemble U.S. TV miniseries—serialized TV shows that run over a two-

Episodic Series

Abandoning anthologies, producers and writers increasingly developed episodic series, first used on radio in 1929. In this format, main characters continue from week to week, sets and locales remain the same, and technical crews stay with the program. The episodic series comes in two general types: chapter shows and serial programs.

LaunchPad

Television Drama: Then and Now

Head to LaunchPad to watch clips from two different drama series: one several decades old, and one recent.

Discussion: What evidence of storytelling changes can you see by comparing and contrasting the two clips?

Chapter shows are self-

In contrast to chapter shows, serial programs are open-

Another type of drama is the hybrid, which developed in the early 1980s with the appearance of Hill Street Blues (1981–

TV Information: Our Daily News Culture

For about forty years (from the 1960s to the 2000s), broadcast news, especially on local TV stations, consistently topped print journalism in national research polls that asked which news medium was most trustworthy. Most studies at the time suggested that this has to do with TV’s intimacy as a medium—

Network News

Originally featuring a panel of reporters interrogating political figures, NBC’s weekly Meet the Press (1947–

Over at CBS, the network’s flagship evening news program, The CBS-

After premiering an unsuccessful daily program in 1948, ABC launched a daily news show in 1953, anchored by John Daly—

In 1968, after popular CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite visited Vietnam, CBS produced the documentary Report from Vietnam by Walter Cronkite. At the end of the program, Cronkite offered this terse observation: “It is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could.” Most political observers said that Cronkite’s opposition to the war influenced President Johnson’s decision not to seek reelection. CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images

Cable News Changes the Game

The first 24/7 cable TV news channel, Cable News Network (CNN), premiered in 1980 and was the brainchild of Ted Turner, who had already revolutionized cable with his Atlanta-

Cable news has significantly changed the TV news game by offering viewers information and stories in a 24/7 loop. Rather than waiting until 5:30 or 6:30 P.M. to watch the national network news, viewers can access news updates and breaking stories at any time. Cable news also challenges the network program formulas. Daily opinion programs, such as MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow Show and Fox News’ Sean Hannity Show, often celebrate argument, opinion, and speculation over traditional reporting based on verified facts. These programs emerged primarily because of their low cost compared with that of traditional network news. At the same time, satirical “fake news” programs like The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and The Colbert Report have challenged traditional news outlets by discussing the news in larger contexts, something the conventional thirty-

Reality TV and Other Enduring Genres

Up to this point, we have focused on long-

Reality-

Another growing trend is Spanish-

Public Television Struggles to Find Its Place

Another key programmer in TV history has been public television. Under President Lyndon Johnson, and in response to a report from the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television, Congress passed the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967, establishing the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) and later, in 1969, the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). In part, Congress intended public television to target viewers who were “less attractive” to commercial networks and advertisers. Besides providing programs for viewers over age fifty, public television has figured prominently in programming for audiences under age twelve, with children’s series like Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood (1968–

The original Carnegie Commission report also recommended that Congress create a financial plan to provide long-

Despite support from the Obama administration, in 2011 the Republican-

Also troubling to public television (in contrast to public radio, which increased its audience from two million listeners per week in 1980 to more than thirty million per week in 2010) is that the audience for PBS has declined. PBS content chief John Boland attributed the loss to the same market fragmentation and third-

LaunchPad

What Makes Public Television Public?

TV executives and critics explain how public television is different from broadcast and cable networks.

Discussion: In a commercial media system that includes hundreds of commercial channels, what do you see as the role of public systems like PBS and NPR?

The most influential children’s show in TV history, Sesame Street (1969–

Media Literacy and the Critical Process

TV and the State of Storytelling

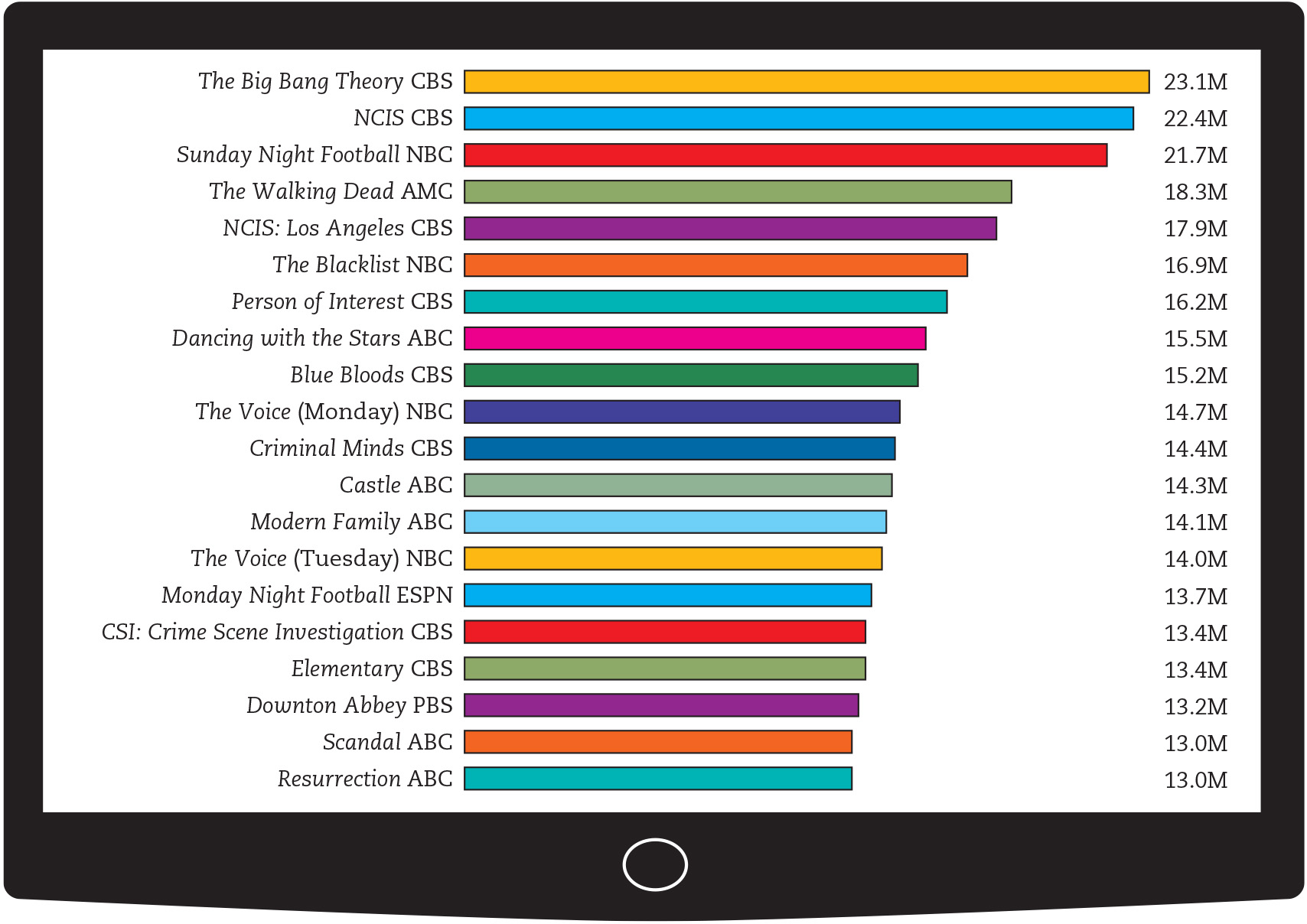

The rise of the reality program over the past decade has more to do with the cheaper cost of this genre than with the wild popularity of these programs. In fact, in the history of television and viewer numbers, traditional sitcoms and dramas—

1 DESCRIPTION. Pick a current reality program and a current sitcom or drama. Choose programs that either started in the last year or two or have been on television for roughly the same period of time. Now develop a “viewing sheet” that allows you to take notes as you watch the two programs over a three-

2 ANALYSIS. Look for patterns and differences in the ways stories are told in the two programs. At a general level, what are the conflicts about? (For example, are they about men versus women, managers versus employees, tradition versus change, individuals versus institutions, honesty versus dishonesty, authenticity versus artificiality?) How complicated or simple are the tensions in the two programs, and how are problems resolved? Are there some conflicts that you feel should not be permitted—

3 INTERPRETATION. What do some of the patterns mean? What seems to be the point of each program? What do the programs say about relationships, values, masculinity or femininity, power, social class, and so on?

4 EVALUATION. What are the strengths and weaknesses of each program? Which program would you judge as better at telling a compelling story that you want to watch each week? How could each program improve its storytelling?

5 ENGAGEMENT. Either through online forums or via personal contacts, find other viewers of these programs. Ask them follow-