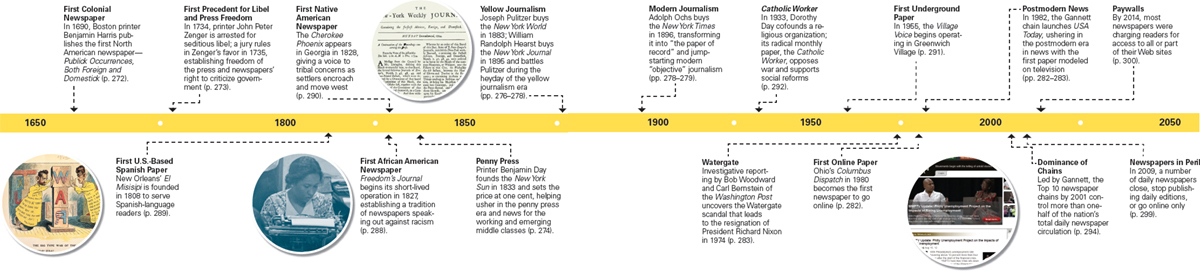

The Evolution of American Newspapers

The idea of news is as old as language itself. The earliest news was passed along orally from family to family, from tribe to tribe, by community leaders and oral historians. The earliest known written news account, or news sheet, Acta Diurna (Latin for “daily events”), was developed by Julius Caesar and posted in public spaces and on buildings in Rome in 59 BCE. Even in its oral and early written stages, news informed people on the state of their relations with neighboring tribes and towns. The development of the printing press in the fifteenth century greatly accelerated a society’s ability to send and receive information. Throughout history, news has satisfied our need to know things we cannot experience personally. Newspapers today continue to document daily life and bear witness to both ordinary and extraordinary events.

Colonial Newspapers and the Partisan Press

The novelty and entrepreneurial stages of print media development first happened in Europe with the rise of the printing press. In North America, the first newspaper, Publick Occurrences, Both Foreign and Domestick, was published on September 25, 1690, by Boston printer Benjamin Harris. The colonial government objected to Harris’s negative tone regarding British rule, and local ministers were offended by his published report that the king of France had an affair with his son’s wife. The newspaper was banned after one issue.

In 1704, the first regularly published newspaper appeared in the American colonies—

Another important colonial paper, the New-

By 1765, about thirty newspapers operated in the American colonies, with the first daily paper beginning in 1784. Newspapers were of two general types: political or commercial. Their development was shaped in large part by social, cultural, and political responses to British rule and by its eventual overthrow. The gradual rise of political parties and the spread of commerce also influenced the development of early papers. Although the political and commercial papers carried both party news and business news, they had different agendas. Political papers, known as the partisan press, generally pushed the plan of the particular political group that subsidized the paper. The commercial press, by contrast, served business leaders, who were interested in economic issues. Both types of journalism left a legacy. The partisan press gave us the editorial pages, while the early commercial press was the forerunner of the business section.

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, even the largest of these papers rarely reached a circulation of fifteen hundred. Readership was primarily confined to educated or wealthy men who controlled local politics and commerce. During this time, though, a few pioneering women operated newspapers, including Elizabeth Timothy, the first American woman newspaper publisher (and mother of eight children). After her husband died of smallpox in 1738, Timothy took over the South Carolina Gazette, established in 1734 by Benjamin Franklin and the Timothy family. Also during this period, Anna Maul Zenger ran the New-

The Penny Press Era: Newspapers Become Mass Media

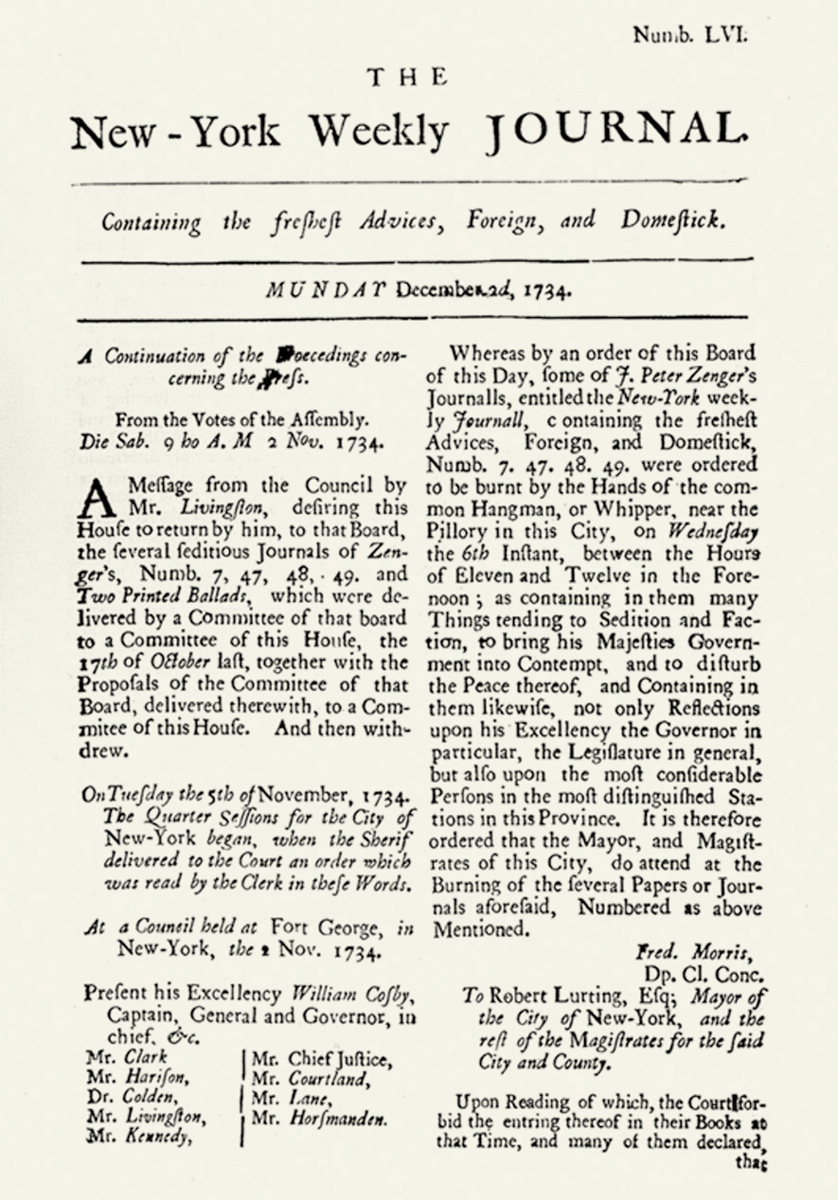

During the colonial period, New York printer John Peter Zenger was arrested for seditious libel. He eventually won his case, which established the precedent that today allows U.S. journalists and citizens to criticize public officials. In this 1734 issue, Zenger’s New-

By the late 1820s, the average newspaper cost six cents a copy and was sold through yearly subscriptions priced at ten to twelve dollars. Because that price was more than a week’s salary for most skilled workers, newspaper readers were mostly affluent. By the 1830s, however, the Industrial Revolution made possible the replacement of expensive handmade paper with cheaper machine-

Day and the New York Sun

In 1833, printer Benjamin Day founded the New York Sun with no subscriptions and the price set at one penny. The Sun—whose slogan was “It shines for all”—highlighted local events, scandals, police reports, and serialized stories. Like today’s supermarket tabloids, the Sun fabricated stories, including the infamous moon hoax, which reported “scientific” evidence of life on the moon. Within six months, the Sun’s lower price had generated a circulation of eight thousand, twice that of its nearest New York competitor.

The Sun’s success initiated a wave of penny papers that favored human-

Bennett and the New York Morning Herald

The penny press era also featured James Gordon Bennett’s New York Morning Herald, founded in 1835. Bennett, considered the first U.S. press baron, freed his newspaper from political influence. He established an independent paper serving middle-

Changing Economics and the Founding of the Associated Press

The penny papers were innovative. For example, they were the first to assign reporters to cover crime, and readers enthusiastically embraced the reporting of local news and crime. By gradually separating daily front-

In 1848, six New York newspapers formed a cooperative arrangement and founded the Associated Press (AP), the first major news wire service. Wire services began as commercial organizations that relayed news stories and information around the country and the world using telegraph lines and, later, radio waves and digital transmissions. In the case of the AP, the New York papers provided access to both their own stories and those from other newspapers. In the 1850s, papers started sending reporters to cover Washington, D.C., and in the early 1860s, more than a hundred reporters from northern papers went south to cover the Civil War, relaying their reports back to their home papers via telegraph and wire services. The news wire companies enabled news to travel rapidly from coast to coast and set the stage for modern journalism.

The marketing of news as a product and the use of modern technology to dramatically cut costs gradually elevated newspapers from an entrepreneurial stage to the status of a mass medium. By adapting news content, penny papers captured the middle-

The Age of Yellow Journalism: Sensationalism and Investigation

The rise of competitive dailies and the penny press triggered the next significant period in American journalism. In the late 1800s, yellow journalism emphasized profitable papers that carried exciting human-

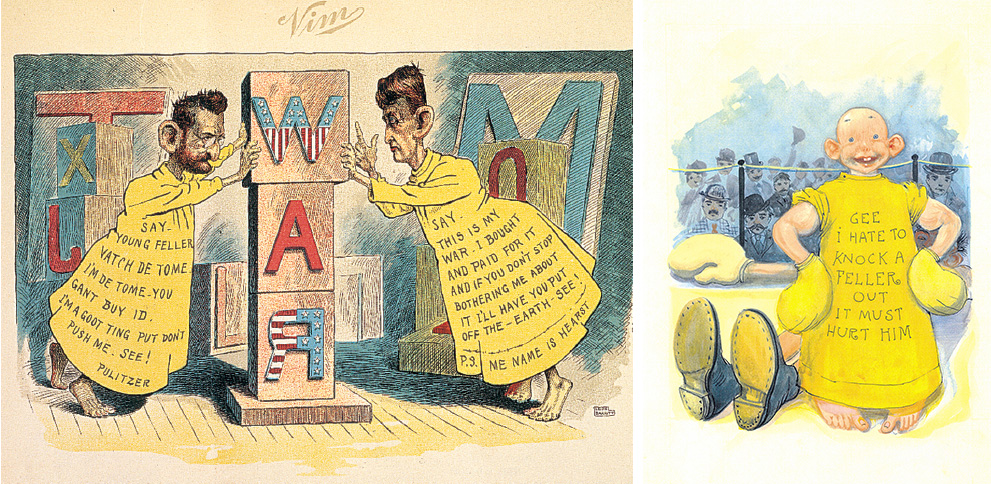

During this period, a newspaper circulation war pitted Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World against William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal. A key player in the war was the first popular cartoon strip, The Yellow Kid, created in 1895 by artist R. F. Outcault, who once worked for Thomas Edison. The phrase yellow journalism has since become associated with the cartoon strip, which was shuttled back and forth between the Hearst and Pulitzer papers during their furious battle for readers in the mid to late 1890s.

Generally considered America’s first comic-

Pulitzer and the New York World

Joseph Pulitzer, a Jewish-

In 1883, Pulitzer bought the New York World for $346,000. He encouraged plain writing and the inclusion of maps and illustrations to help immigrant and working-

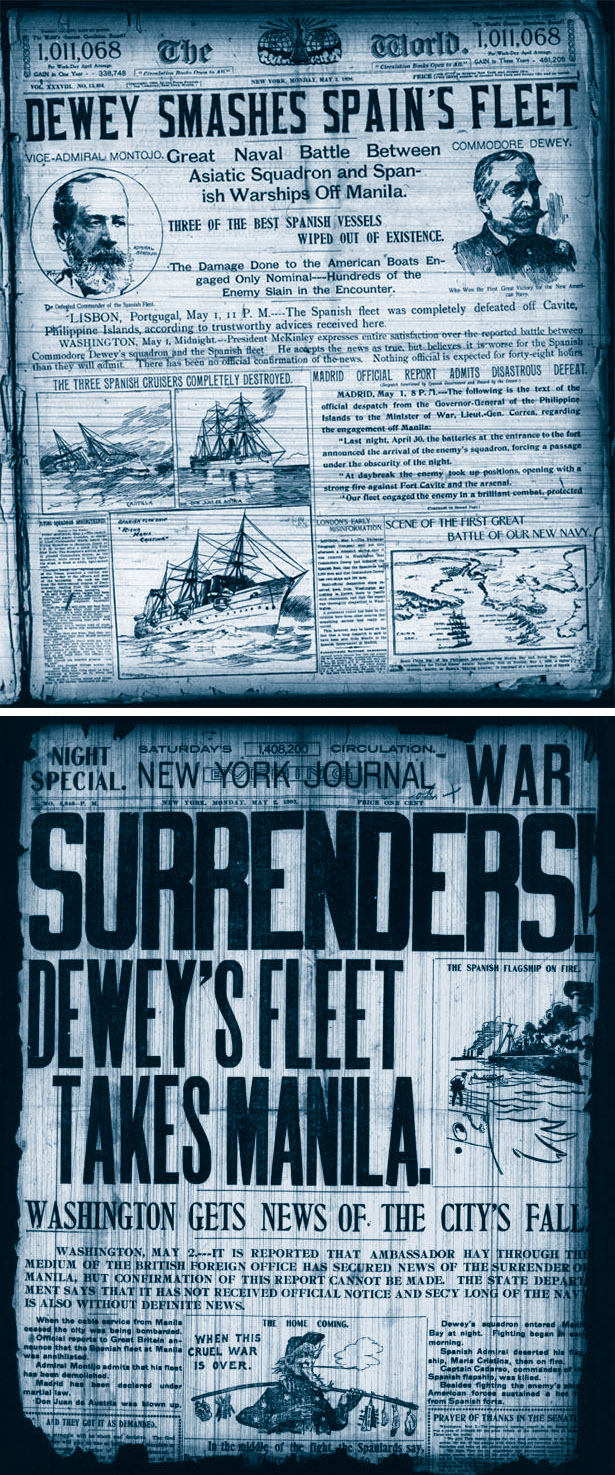

The World (top) and the New York Journal (bottom) cover the same story in May 1898. New York Public Library/Art Resource, NY (top and bottom)

The World reflected the contradictory spirit of the yellow press. It crusaded for improved urban housing, better conditions for women, and equitable labor laws. It campaigned against monopoly practices by AT&T, Standard Oil, and Equitable Insurance. Such popular crusades helped lay the groundwork for tightening federal antitrust laws in the early 1910s. At the same time, Pulitzer’s paper manufactured news events and staged stunts, such as sending star reporter Nellie Bly around the world in seventy-

Pulitzer created a lasting legacy by leaving $2 million to start the graduate school of journalism at Columbia University in 1912. In 1917, part of Pulitzer’s Columbia endowment established the Pulitzer Prizes, the prestigious awards given each year for achievements in journalism, literature, drama, and music.

Hearst and the New York Journal

The World faced its fiercest competition when William Randolph Hearst bought the New York Journal (a penny paper founded by Pulitzer’s brother Albert). Before moving to New York, the twenty-

Taking his cue from Bennett and Pulitzer, Hearst focused on lurid, sensational stories and appealed to immigrant readers by using large headlines and bold layout designs. To boost circulation, the Journal invented interviews, faked pictures, and encouraged conflicts that might result in a story. One tabloid account describes “tales about two-

Hearst is remembered as an unscrupulous publisher who once hired gangsters to distribute his newspapers. He was also, however, considered a champion of the underdog, and his paper’s readership soared among the working and middle classes. In 1896, the Journal’s daily circulation reached 450,000, and by 1897, the Sunday edition of the paper rivaled the 600,000 circulation of the World. By the 1930s, Hearst’s holdings included more than forty daily and Sunday papers, thirteen magazines (including Good Housekeeping and Cosmopolitan), eight radio stations, and two film companies. In addition, he controlled King Features Syndicate, which sold and distributed articles, comics, and features to many of the nation’s dailies. Hearst, the model for Charles Foster Kane, the ruthless publisher in Orson Welles’s classic 1940 film Citizen Kane, operated the largest media business in the world—