Challenges Facing Newspapers Today

Publishers and journalists today face worrisome issues, such as the decline in newspaper readership and the failure of many papers to attract younger readers. However, other problems persist as newspapers continue to converge with the Internet and grapple with the future of digital news.

Readership Declines in the United States

The decline in daily newspaper readership actually began during the Great Depression with the rise of radio. Between 1931 and 1939, six hundred newspapers ceased operation. Another circulation crisis occurred from the late 1960s through the 1970s with the rise in network television viewing and greater competition from suburban weeklies. In addition, with an increasing number of women working full-

Throughout the first decade of the twenty-

Companies have started to experiment in a big way with a variety of new revenue streams and major organizational changes. Some of the bright opportunities—

Digital pay plans are being adopted at 450 of the country’s 1,380 dailies and appear to be working not just at The New York Times but also at small and mid-

Remarkably, while the United States continues to experience declines in newspaper readership and advertising dollars, many other nations—

Going Local: How Small and Campus Papers Retain Readers

Despite the doomsday headlines and predictions about the future of newspapers, it is important to note, as Pew’s State of the News Media 2010 report observed, that the problems of the newspaper business “are not uniform across the industry.” In fact, according to the report, “Small dailies and community weeklies, with the exception of some that are badly positioned or badly managed,” still do better than many “big-

Smaller newspapers continue to do better today for several reasons. First, small towns and cities often don’t have local TV stations, big-

Finally, because smaller newspapers tend to be more consensus-

Blogs Challenge Newspapers’ Authority Online

The rise of blogs in the late 1990s brought amateurs into the realm of professional journalism. It was an awkward meeting. As National Press Club president Doug Harbrecht said to conservative blogger Matt Drudge in 1998 while introducing him to the press club’s members, “There aren’t many in this hallowed room who consider you a journalist. Real journalists . . . pride themselves on getting it first and right; they get to the bottom of the story, they bend over backwards to get the other side. Journalism means being painstakingly thorough, even-

LaunchPad

Community Voices: Weekly Newspapers

Journalists discuss the role of local newspapers in their communities.

Discussion: In a democratic society, why might having many community voices in the news media be a good thing?

By 2005, the wary relationship between journalism and blogging began to change. Blogging became less a journalistic sideline and more a viable main feature. Established journalists left major news organizations to begin new careers in the blogosphere. For example, in 2007, top journalists John Harris and Jim VandeHei left the Washington Post to launch Politico, a national blog (and, secondarily, a local newspaper) about Capitol Hill politics. Another breakthrough moment occurred when the Talking Points Memo blog, headed by Joshua Micah Marshall, won a George Polk Award for legal reporting in 2008. Explaining his view of blogging, Marshall has said, “I think of us as journalists; the medium we work in is blogging. We have kind of broken free of the model of discrete articles that have a beginning and end. Instead, there are an ongoing series of dispatches.”52 Increasingly, because of qualified journalists moving online, Pew reports that sites that started out as opinionated blogs have grown into legitimate news venues:

Digital players have exploded onto the news scene, bringing technological know-

What distinguishes the best online news from so many opinion blogs still out there is the reliance on old-

Convergence: Newspapers Struggle in the Move to Digital

Because of their local monopoly status, many newspapers were slower than other media to confront the challenges of the Internet. But faced with competition from the 24/7 news cycle on cable, newspapers responded by developing online versions of their papers. While some observers think newspapers are on the verge of extinction as the digital age eclipses the print era, the industry is no dinosaur. In fact, the history of communication demonstrates that older mass media have always adapted; so far, books, newspapers, and magazines have adjusted to the radio, television, and movie industries. And with nearly fifteen hundred North American daily papers going online in 2010, newspapers are solving one of the industry’s major economic headaches: the cost of newsprint. After salaries, paper is the industry’s largest expense, typically accounting for more than 25 percent of a newspaper’s total cost.

Online newspapers are truly taking advantage of the flexibility the Internet offers. Because space is not an issue online, newspapers can post stories and readers’ letters that they aren’t able to print in the paper edition. They can also run longer stories with more in-

Among the valuable resources that online newspapers offer are hyperlinks to Web sites that relate to stories and that link news reports to an archive of related articles. Free of charge or for a modest fee, a reader can search the newspaper’s database from home and investigate the entire sequence and history of an ongoing story, such as a trial, over the course of several months. Taking advantage of the Internet’s multimedia capabilities, online newspapers offer readers the ability to stream audio and video files—

However, these advances have yet to pay off. Online ads in the United States accounted for about 13 percent of a newspaper’s advertising in 2010—

The New York Times began charging readers for access to all online content in early 2011, via either a print subscription or a stand-

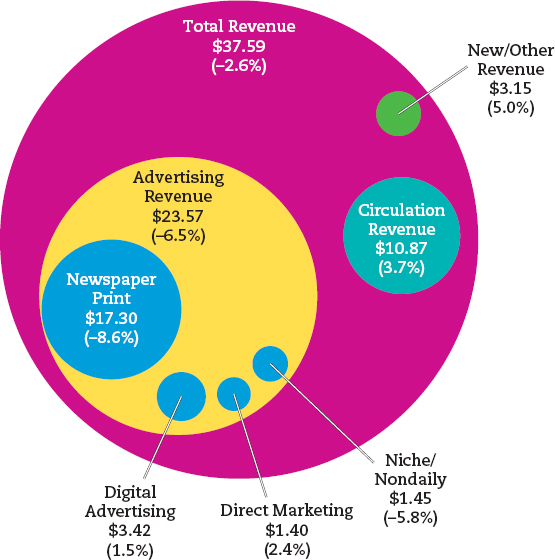

By 2014, online ad sales for newspapers accounted for about 17 percent of U.S. newspapers’ advertising revenue, suggesting that online sales on average had risen just 1 percent a year since 2010. The Newspaper Association of America reported that print ad sales in 2013 had declined another 8.6 percent, which represented a loss of $1.6 billion. In terms of digital advertising—

One of the business mistakes that most newspaper executives made near the beginning of the Internet age was giving away online content for free. Whereas their print versions always had two revenue streams—

An interesting case in the paywall experiments is the New York Times. In 2005, the paper began charging online readers for access to its editorials and columns, but the rest of the site was free. This system lasted only until 2007. But starting in March 2011, the paper added a paywall—

In the years that followed, over 150 newspapers, including many small ones, launched various paywalls, many of them based on the New York Times’ metered model, trying to reverse years of giving away their print content online for free. Larger metro dailies, including the Boston Globe, Dallas Morning News, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, and Los Angeles Times, have also started their own paywalls and metered models. But in 2014, the Nieman Journalism Lab reported on a number of studies and a report on Gannett’s experiments with its various paywalls and concluded: “When you announce a paywall, you get a one-

New Models for Journalism

In response to the challenges newspapers face, a number of journalists, economists, and citizens are calling for new business models—

Additional ideas are coming from universities (where journalism school enrollments are actually increasing). For example, the dean of Columbia University’s Journalism School (started once upon a time with money bequeathed by nineteenth-

- News organizations “substantially devoted to reporting on public affairs” should be allowed to operate as nonprofit entities in order to take in tax-

deductible contributions while still collecting ad and subscription revenues. For example, the Poynter Institute owns and operates the Tampa Bay Times (formerly the St. Petersburg Times), Florida’s largest newspaper. As a nonprofit, the Times is protected from the unrealistic 16 to 20 percent profit margins that publicly held newspapers had been expected to earn in the 1980s and 1990s. - Public radio and TV, through federal reforms in the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, should reorient their focus to “significant local news reporting in every community served by public stations and their Web sites.”

- Operating their own news services or supporting regional news organizations, public and private universities “should become ongoing sources of local, state, specialized subject and accountability news reporting as part of their educational mission.”

- A national Fund for Local News should be created with money the Federal Communications Commission collects from “telecom users, television and radio broadcast licensees, or Internet service providers.”

- News services, nonprofit organizations, and government agencies should use the Internet to “increase the accessibility and usefulness of public information collected by federal, state, and local governments.”

As the journalism industry continues to reinvent itself and tries new avenues to ensure its future, not every “great” idea will work out. Some of the immediate backlash to Downie and Schudson’s report raised questions about the government becoming involved with traditionally independent news media. What is important, however, is that newspapers continue to experiment with new ideas and business models so that they can adapt and even thrive in the Internet age. (For more on the challenges facing journalism, see Chapter 14.)

Alternative Voices

The combination of the online news surge and traditional newsroom cutbacks has led to a phenomenon known as citizen journalism, or citizen media (or community journalism for those projects in which the participants might not be citizens). As a grassroots movement, citizen journalism refers to people—

Back in 2008, one study reported that more than one thousand community-

Beyond the citizen model, another Pew study in 2013 identified 170 specific nonprofit news organizations “with minimal staffs and modest budgets” that “range from the nationally known [like the investigative site ProPublica] to the hyperlocal” that are trying to compensate for the loss of close to 20,000 commercial newsroom jobs over the last decade.63 In 2014, Pew studied 438 of these newer digital sites: “Of the 402 outlets that identified a business model, slightly more than half (204) are nonprofits compared with 196 that are commercial entities. In recent years, the nonprofit model has attracted a significant amount of foundation funding for news gathering.” In its State of the News Media 2014 report, Pew “estimated that roughly $150 million in philanthropy now goes to journalism annually. Some of that is used as seed money for digital nonprofit news organizations: 61% of the nonprofit news organizations surveyed by Pew Research began with a large start-

Most journalists and many citizens want to see more professional models of journalism develop in the digital age so that people can decrease their reliance on unedited video footage and untrained amateurs as key sources for news. While many community-