The Early History of Magazines

The first magazines appeared in seventeenth-

The First Magazines

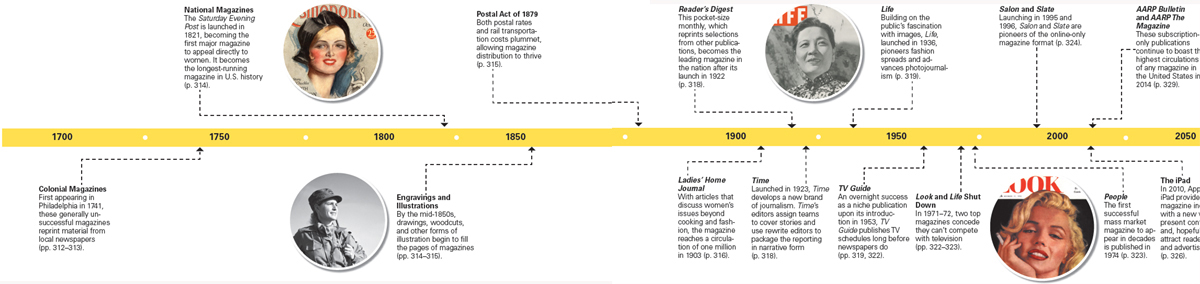

The first issue of Benjamin Franklin’s General Magazine and Historical Chronicle appeared in January 1741. Although it lasted only six months, Franklin found success in other publications, like his annual Poor Richard’s Almanac, which started in 1732 and lasted twenty-

The first political magazine, called the Review, appeared in London in 1704. Edited by political activist and novelist Daniel Defoe (author of Robinson Crusoe), the Review was printed sporadically until 1713. Like the Nation, the National Review, and the Progressive in the United States today, early European magazines were channels for political commentary and argument. These periodicals looked like newspapers of the time, but they appeared less frequently and were oriented toward broad domestic and political commentary rather than recent news.

Regularly published magazines or pamphlets, such as the Tatler and the Spectator, also appeared in England around this time. They offered poetry, politics, and philosophy for London’s elite, and they served readerships of a few thousand. The first publication to use the term magazine was Gentleman’s Magazine, which appeared in London in 1731 and consisted of reprinted articles from newspapers, books, and political pamphlets. Later, the magazine began publishing original work by such writers as Defoe, Samuel Johnson, and Alexander Pope.

Magazines in Colonial America

Without a substantial middle class, widespread literacy, or advanced printing technology, magazines developed slowly in colonial America. Like the partisan newspapers of the time, these magazines served politicians, the educated, and the merchant classes. Paid circulations were low—

The first colonial magazines appeared in Philadelphia in 1741, about fifty years after the first newspapers. Andrew Bradford started it all with American Magazine, or A Monthly View of the Political State of the British Colonies. Three days later, Benjamin Franklin’s General Magazine and Historical Chronicle appeared. Bradford’s magazine lasted only three monthly issues, due to circulation and postal obstacles that Franklin, who had replaced Bradford as Philadelphia’s postmaster, put in its way. For instance, Franklin mailed his magazine without paying the high postal rates that he subsequently charged others. Franklin’s magazine primarily duplicated what was already available in local papers. After six months it, too, stopped publication.

Nonetheless, following the Philadelphia experiments, magazines began to emerge in the other colonies, beginning in Boston in the 1740s. The most successful magazines simply reprinted articles from leading London periodicals, keeping readers abreast of European events. These magazines included New York’s Independent Reflector and the Pennsylvania Magazine, edited by activist Thomas Paine, which helped rally the colonies against British rule. By 1776, about a hundred colonial magazines had appeared and disappeared. Although historians consider them dull and uninspired for the most part, these magazines helped launch a new medium that caught on after the American Revolution.

U.S. Magazines in the Nineteenth Century

After the revolution, the growth of the magazine industry in the newly independent United States remained slow. Delivery costs remained high, and some postal carriers refused to carry magazines because of their weight. Only twelve magazines operated in 1800. By 1825, about a hundred magazines existed, although about another five hundred had failed between 1800 and 1825. Nevertheless, during the first quarter of the nineteenth century, most communities had their own weekly magazines. These magazines featured essays on local issues, government activities, and political intrigue, as well as material reprinted from other sources. They sold some advertising but were usually in precarious financial straits because of their small circulations.

As the nineteenth century progressed, the idea of specialized magazines devoted to certain categories of readers developed. Many early magazines were overtly religious and boasted the largest readerships of the day. The Methodist Christian Journal and Advocate, for example, claimed twenty-

The nineteenth century also saw the birth of the first general-

National, Women’s, and Illustrated Magazines

With increases in literacy and public education, the development of faster printing technologies, and improvements in mail delivery (due to rail transportation), a market was created for more national magazines like the Saturday Evening Post. Whereas in 1825 one hundred magazines struggled for survival, by 1850 nearly six hundred magazines were being published regularly. (Thousands of others lasted less than a year.) Significant national magazines of the era included Graham’s Magazine (1840–

Besides the move to national circulation, other important developments in the magazine industry were under way. In 1828, Sarah Josepha Hale started the first magazine directed exclusively to a female audience: the Ladies’ Magazine. In addition to carrying general-

The other major development in magazine publishing during the mid-

Famed portrait photographer Mathew Brady commissioned many photographers to help him document the Civil War. (Although all the resulting photos were credited “Photograph by Brady,” he did not take them all.) This effort allowed people at home to see and understand the true carnage of the war. Photo critics now acknowledge that some of Brady’s photos were posed or reenactments. © Bettmann/Corbis