The Practice of Public Relations

Today, there are more than seven thousand PR firms in the United States, plus thousands of additional PR departments within corporate, government, and nonprofit organizations.12 Since the 1980s, the formal study of public relations has grown significantly at colleges and universities. By 2014, the Public Relations Student Society of America (PRSSA) had more than eleven thousand members and over three hundred chapters in colleges and universities. As certified PR programs have expanded (often requiring courses or a minor in journalism), the profession has relied less and less on its traditional practice of recruiting journalists for its workforce. At the same time, new courses in professional ethics and issues management have expanded the responsibility of future practitioners. In this section, we discuss the differences between public relations agencies and in-

422

Approaches to Organized Public Relations

The Public Relations Society of America (PRSA) offers this simple and useful definition of PR: “Public relations helps an organization and its publics adapt mutually to each other.” To carry out this mutual communication process, the PR industry uses two approaches. First, there are independent PR agencies whose sole job is to provide clients with PR services. Second, most companies, which may or may not also hire independent PR firms, maintain their own in-

Many large PR firms are owned by, or are affiliated with, multinational communications holding companies, such as Publicis, Omnicom, WPP, and Interpublic (see Table 12.1). Three of the largest PR agencies—

| Rank | Agency | Parent Firm | Headquarters | Revenue |

| 1 | Edelman | Independent | New York/Chicago | $741 |

| 2 | Weber Shandwick | Interpublic | New York | $567 |

| 3 | Fleishman- |

Omnicom | St. Louis | $551 |

| 4 | MSL Group | Publicis | Paris | $501 |

| 5 | Burson- |

WPP | New York | $466 |

| 6 | Ketchum | Omnicom | New York | $464 |

| 7 | Hill+Knowlton Strategies | WPP | New York | $390 |

| 8 | Ogilvy Public Relations | WPP | New York | $296 |

| 9 | BlueDigital | BlueFocus Communication Group | Beijing | $271 |

| 10 | Brunswick Group | Independent | London | $231 |

In contrast to these external agencies, most PR work is done in-

423

Performing Public Relations

Public relations, like advertising, pays careful attention to the needs of its clients—

In addition, PR personnel (both PR technicians, who handle daily short-

Research: Formulating the Message

One of the most essential practices in the PR profession is doing research. Just as advertising is driven today by demographic and psychographic research, PR uses similar strategies to project messages to appropriate audiences. Because it has historically been difficult to determine why particular PR campaigns succeed or fail, research has become the key ingredient in PR forecasting. Like advertising, PR makes use of mail, telephone, and Internet surveys and focus group interviews—

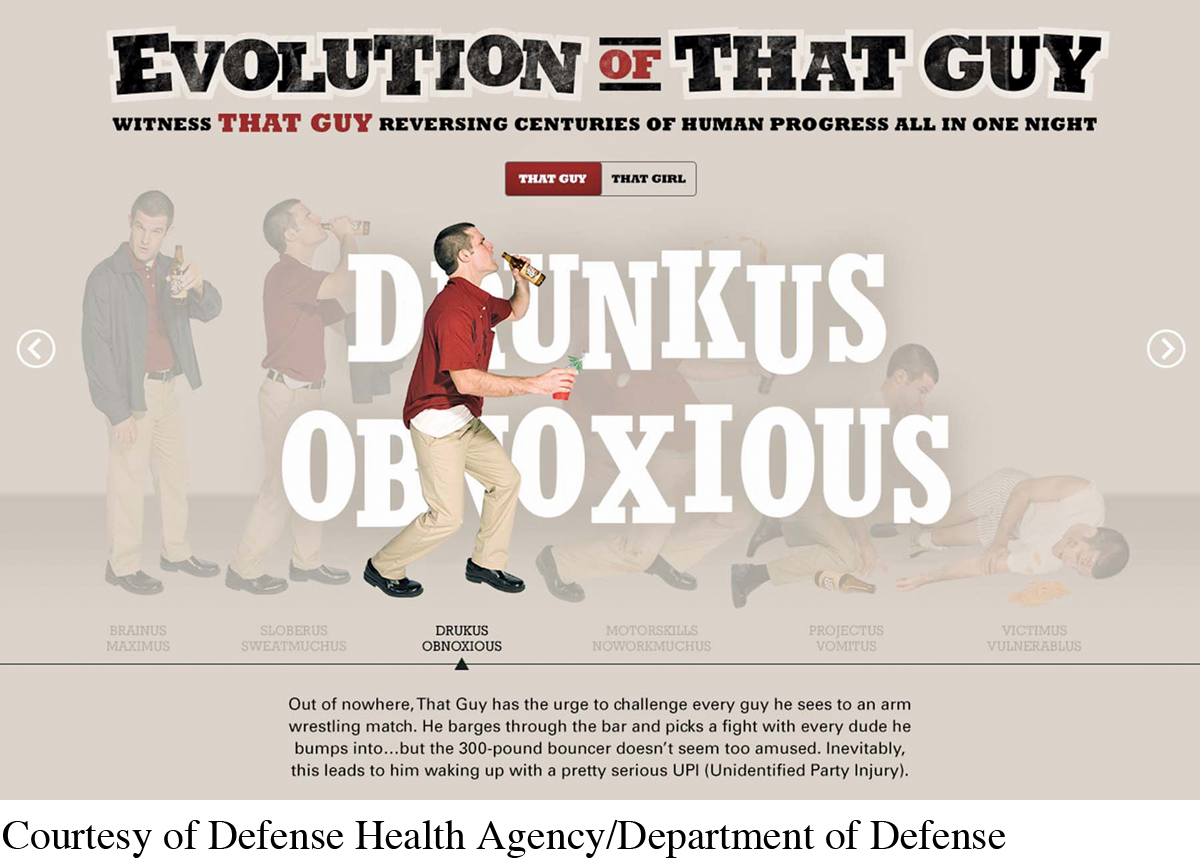

Research also helps PR firms focus the campaign message. For example, the Department of Defense hired the PR firm Fleishman-

424

Conveying the Message

One of the chief day-

Press releases, or news releases, are announcements written in the style of news reports that give new information about an individual, a company, or an organization and pitch a story idea to the news media. In issuing press releases, PR agents hope that their client information will be picked up by the news media and transformed into news reports. Through press releases, PR firms manage the flow of information, controlling which media get what material in which order. (A PR agent may even reward a cooperative reporter by strategically releasing information.) News editors and broadcasters sort through hundreds of releases daily to determine which ones contain the most original ideas or are the most current. Most large media institutions rewrite and double-

Since the introduction of portable video equipment in the 1970s, PR agencies and departments have also been issuing video news releases (VNRs)—thirty-

425

The equivalent of VNRs for nonprofits are public service announcements (PSAs): fifteen-

Today, the Internet is an essential avenue for distributing PR messages. Companies upload or e-

Media Relations

PR managers specializing in media relations promote a client or an organization by securing publicity or favorable coverage in the news media. This often requires an in-

PR agents who specialize in media relations also recommend advertising to their clients when it seems appropriate. Unlike publicity, which is sometimes outside a PR agency’s control, paid advertising may help focus a complex issue or a client’s image. Publicity, however, carries the aura of legitimate news and thus has more credibility than advertising. In addition, media specialists cultivate associations with editors, reporters, freelance writers, and broadcast news directors to ensure that press releases or VNRs are favorably received (see “Examining Ethics: Public Relations and Bananas” on page 428).

426

CASE STUDY

The NFL’s Concussion Crisis

T he stylized violence of hard-

But this celebration of big hits has begun to seem callous and cruel, as decades of professional football popularity have produced retired players in their thirties, forties, fifties, and older who are experiencing the trauma of brain damage. The diagnosis is CTE, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which can leave its victims with problems like hearing loss, memory loss, aggression, depression, and overall dementia. The concussion problem for football players is caused not only by the big concussions that knock them unconscious but also by what researchers call “subconcussions”—the hits to the head that happen many times during a game, and that can number in the hundreds and thousands over the course of a career.

CTE can best be confirmed upon death, when the interior of the brain can be examined to show the buildup of a protein that strangles neurons—

In the 2013 book League of Denial: The NFL, Concussions, and the Battle for Truth, ESPN investigative reporters (and brothers) Mark Fainaru-

The NFL has a lot to protect. Their business is a $10 billion industry, and the very nature of the game requires hulking players to knock their heads and bodies into other very large players, often running at full speed.1 As a result, more than four thousand retired players are suing the NFL to cover their head trauma expenses. These stories have begun to change the country’s attitude toward the game. News stories about the effects of football concussions are increasingly common, and youth football league participation has dropped nearly 10 percent in the past two years, as parents have grown scared of the impact of the game on their children’s health.

More recently, the NFL has responded by trying to change the conversation, acknowledging a concussion problem but emphasizing that the game has always evolved toward more safety in rules and technology (suggesting, perhaps, that it’s just a matter of time before this forward march solves the concussion crisis). Indeed, the NFL hired a public relations counsel to help develop the NFLevolution.com site (motto: Forever Forward Forever Football). NFL’s Corporate Communications Department also courted “mommy bloggers” to promote football as a healthy, safe activity for their children.

Yet as players continue to come forward with fears or diagnoses of CTE, and as long as the game (and business) of football continues to be played this way, the NFL’s public relations crisis will likely persist. As Fainaru-

427

Special Events and Pseudo-

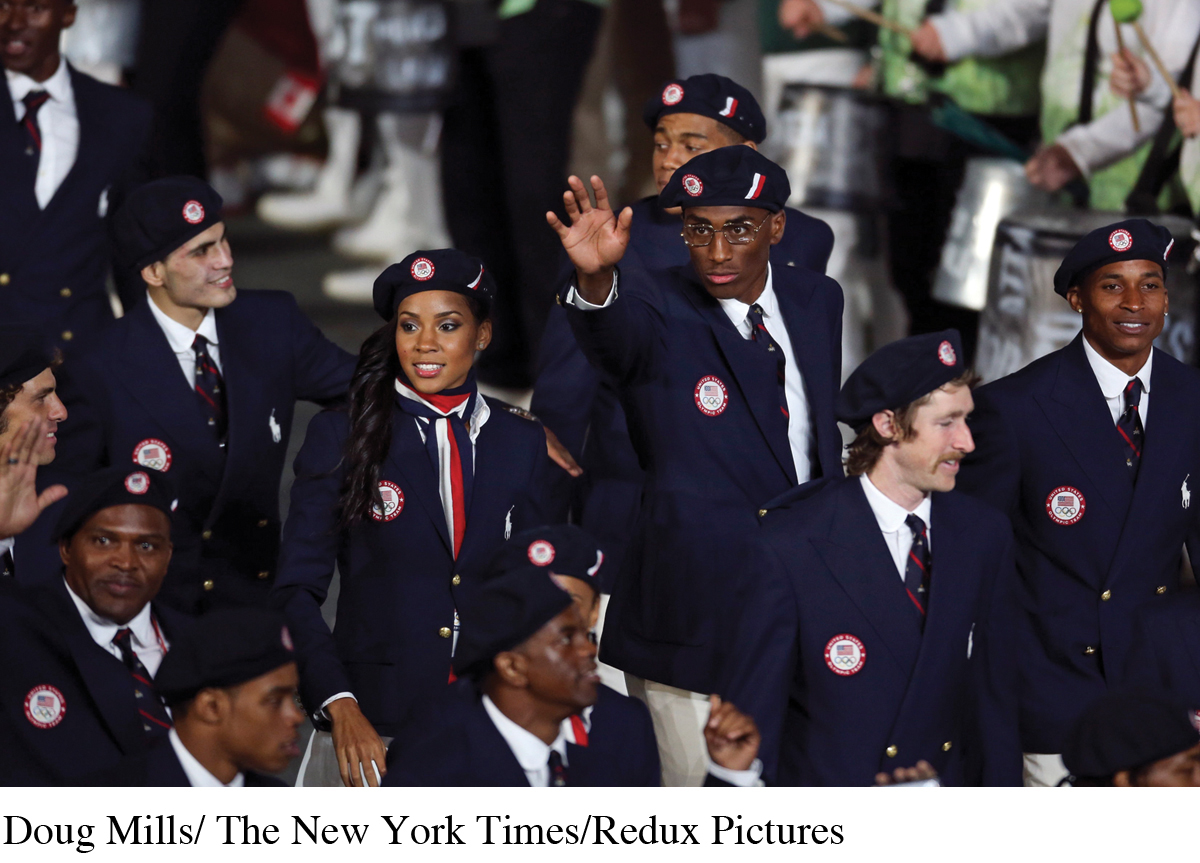

Another public relations practice involves coordinating special events to raise the profile of corporate, organizational, or government clients. Since 1967, for instance, the city of Milwaukee has run Summerfest, a ten-

More typical of special-

In contrast to a special event, a pseudo-

As powerful companies, savvy politicians, and activist groups became aware of the media’s susceptibility to pseudo-

428

EXAMINING ETHICS

Public Relations and Bananas

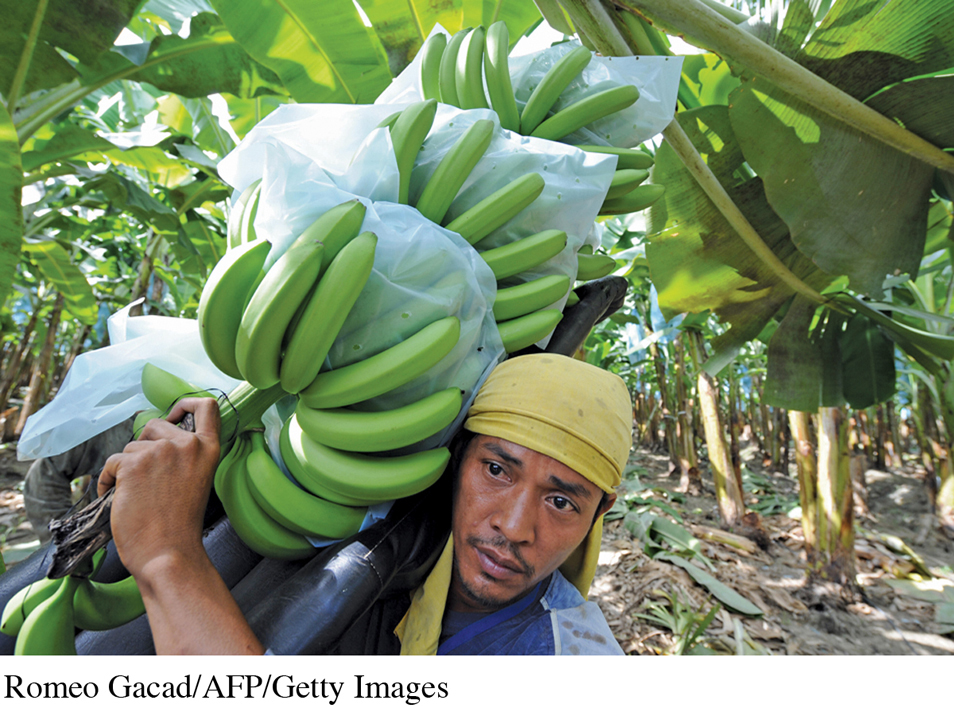

D oing public relations on behalf of bananas doesn’t sound particularly necessary. After all, bananas are the number-

In the early twentieth century, huge banana plantations were established in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Honduras. United Fruit (the predecessor of today’s Chiquita Brands) was the dominant grower and importer of bananas, and was particularly powerful in the small nations of Central America—

In another black eye for the banana industry, Dole and Del Monte, two of today’s largest banana producers, were sued in 2012 by more than one thousand banana plantation workers for using a pesticide that had been banned in the United States in 1979. Bloomberg reported that the pesticide, dibromochloropropane (DBCP), “has been linked to sterility, miscarriages, birth defects, cancer, eye problems, skin disorders and kidney damage,” and that workers argued they had not been informed of the dangers or issued protective equipment.1

Now the good news for bananas and public relations: In 2001, Dole Food Company responded to increasing consumer interest by producing organic bananas for the first time. Although it still produces bananas that are not certified as organic, it is now the leading producer of organic bananas in the world. In 2007, Dole improved communication of its organic program with the launch of doleorganic.com, and began labeling each bunch of organic bananas sold with a sticker that identifies the farm that produced the bananas. The sticker reads, “Visit the Farm at doleorganic.com,” and includes the country of origin and a three-

429

Community and Consumer Relations

Another responsibility of PR is to sustain goodwill between an agency’s clients and the public. The public is often seen as two distinct audiences: communities and consumers.

Companies have learned that sustaining close ties with their communities and neighbors not only enhances their image and attracts potential customers but also promotes the idea that the companies are good citizens. As a result, PR firms encourage companies to participate in community activities, such as hosting plant tours and open houses, making donations to national and local charities, and participating in town events like parades and festivals. In addition, more progressive companies may also get involved in unemployment and job-

In terms of consumer relations, PR has become much more sophisticated since 1965, when Unsafe at Any Speed, Ralph Nader’s groundbreaking book, revealed safety problems concerning the Chevrolet Corvair. Not only did Nader’s book prompt the discontinuance of the Corvair line, but it also lit the fuse that ignited a vibrant consumer movement. After the success of Nader’s book, along with a growing public concern over corporate mergers and corporations’ lack of accountability to the public, consumers became less willing to readily accept the claims of corporations. As a result of the consumer movement, many newspapers and TV stations hired consumer reporters to track down the sources of customer complaints and embarrass companies by putting them in the media spotlight. Public relations specialists responded by encouraging companies to pay more attention to customers, establish product service and safety guarantees, and ensure that all calls and mail from customers were answered promptly. Today, PR professionals routinely advise clients that satisfied customers mean not only repeat business but also new business, based on a strong word-

Government Relations and Lobbying

While sustaining good relations with the public is a priority, so is maintaining connections with government agencies that have some say in how companies operate in a particular community, state, or nation. Both PR firms and the PR divisions within major corporations are especially interested in making sure that government regulation neither becomes burdensome nor reduces their control over their businesses.

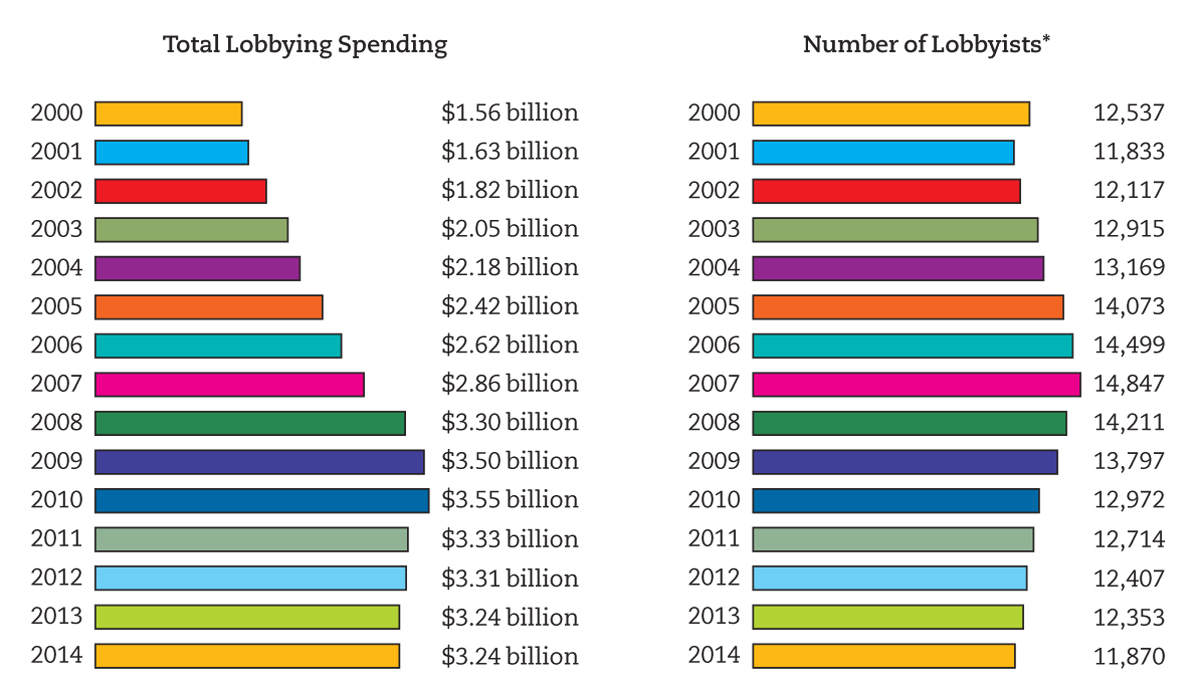

Government PR specialists monitor new and existing legislation, create opportunities to ensure favorable publicity, and write press releases and direct-

430

Lobbying can often lead to ethical problems, as in the case of earmarks and astroturf lobbying. Earmarks are specific spending directives that are slipped into bills to accommodate the interests of lobbyists and are often the result of political favors or outright bribes. In 2006, lobbyist Jack Abramoff (dubbed “the Man Who Bought Washington” in Time) and several of his associates were convicted of corruption related to earmarks, leading to the resignation of leading House members and a decline in the use of earmarks.

Astroturf lobbying is phony grassroots public affairs campaigns engineered by public relations firms. PR firms deploy massive phone banks and computerized mailing lists to drum up support and create the impression that millions of citizens back their client’s side of an issue. For instance, the Center for Consumer Freedom (CCF), an organization that appears to serve the interests of consumers, is actually a creation of the Washington, D.C.–based PR firm Berman & Co. and is funded by the restaurant, food, alcohol, and tobacco industries. According to SourceWatch, which tracks astroturf lobbying, anyone who criticizes tobacco, alcohol, processed food, fatty food, soda pop, pharmaceuticals, animal testing, overfishing, or pesticides “is likely to come under attack from CCF.”16

Public relations firms do not always work for the interests of corporations, however. They also work for other clients, including consumer groups, labor unions, professional groups, religious organizations, and even foreign governments. In 2005, for example, the California Center for Public Health Advocacy—

Presidential administrations also use public relations—

431

Public Relations Adapts to the Internet Age

Historically, public relations practitioners have tried to earn news media coverage (as opposed to buying advertising) to communicate their clients’ messages to the public. While that is still true, the Internet, with its instant accessibility, offers public relations professionals a number of new routes for communicating with the public.

A company or an organization’s Web site has become the home base of public relations efforts. Companies and organizations can upload and maintain their media kits (including press releases, VNRs, images, executive bios, and organizational profiles), giving the traditional news media access to the information at any time. And because everyone can access these corporate Web sites, the barriers between the organization and the groups that PR professionals ultimately want to reach are broken down.

The Web also enables PR professionals to have their clients interact with audiences on a more personal, direct basis through social media tools like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Wikipedia, and blogs. Now people can be “friends” and “followers” of companies and organizations. Corporate executives can share their professional and personal observations and seem downright chummy through a blog (e.g., Whole Foods Market’s blog by CEO John Mackey). Executives, celebrities, and politicians can seem more accessible and personable through a Twitter feed. But social media’s immediacy can also be a problem, especially for those who send messages into the public sphere without considering the ramifications.

Another concern about social media is that sometimes such communications appear without complete disclosure, which is an unethical practice. Some PR firms have edited Wikipedia entries for their clients’ benefit, a practice Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales has repudiated as a conflict of interest. A growing number of companies also compensate bloggers to subtly promote their products, unbeknownst to most readers. Public relations firms and marketers are particularly keen on working with “mom bloggers,” who appear to be independent voices in discussions about consumer products but may receive gifts in exchange for their opinions. In 2009, the Federal Trade Commission instituted new rules requiring online product endorsers to disclose their connections to companies.

As noted earlier, Internet analytics tools enable organizations to monitor what is being said about them at any time. However, the immediacy of social media also means that public relations officials might be forced to quickly respond to a message or an image once it goes viral. For example, when one diner posted a review of a restaurant in Chicago that delivered her ginger salad with a small cockroach, the word spread quickly on Yelp, where she had more than eight hundred friends. The owner wisely apologized on Yelp (six months later—

Public Relations during a Crisis

Since the Ludlow strike, one important duty of PR has been helping a corporation handle a public crisis or tragedy, especially if the public assumes the company is at fault. Disaster management may reveal the best and the worst attributes of the company and its PR firm (see “Case Study: The NFL’s Concussion Crisis” on page 426). Let’s look at two contrasting examples of crisis management and the different ways they were handled.

432

One of the largest environmental disasters so far in the twenty-

A decidedly different approach was taken in the 1982 tragedy involving Tylenol pain-

433