The Web Goes Social

LaunchPad

The Net (1995)Sandra Bullock communicates using her computer in this clip from the 1995 thriller.

Discussion: How does this 1995 movie portray online communication? What does it get right, and what seems silly now?

Aided by faster microprocessors, high-

Social media are new digital media platforms that engage users to create content, add comments, and interact with others. Social media have become a new distribution system for media as well, challenging the one-

Types of Social Media

In less than a decade, a number of different types of social media have evolved, with multiple platforms for the creation of user-

Blogs

Years before there were status updates or Facebook, blogs enabled people to easily post their ideas to a Web site. Popularized with the release of Blogger (now owned by Google) in 1999, blogs contain articles or posts in chronological, journal-

48

Blogs have become part of the information and opinion culture of the Web, giving regular people and citizen reporters a forum for their ideas and views, and providing a place for even professional journalists to informally share ideas before a more formal news story gets published. Some of the leading platforms for blogging include Blogger, WordPress, Tumblr, Weebly, and Wix. But by 2013, the most popular form of blogging was microblogging, with about 241 million active users on Twitter, sending out 500 million tweets (a short message with a 140-

Collaborative Projects

Another Internet development involves collaborative projects in which users build something together, often using wiki (which means “quick” in Hawaiian) technology. Wiki Web sites enable anyone to edit and contribute to them. There are several large wikis, such as Wikitravel (a global travel guide), Wikimapia (combining Google Maps with wiki comments), and WikiLeaks (an organization publishing sensitive documents leaked by anonymous whistleblowers). WikiLeaks gained notoriety for its release of thousands of United States diplomatic cables and other sensitive documents beginning in 2010 (see “Examining Ethics: WikiLeaks, Secret Documents, and Good Journalism on page 506). But the most notable wiki is Wikipedia, an online encyclopedia launched in 2001 that is constantly updated and revised by interested volunteers. All previous page versions of Wikipedia are stored, allowing users to see how each individual topic developed. The English version of Wikipedia is the largest, containing nearly five million articles, but Wikipedias are also being developed in 289 other languages.

Businesses and other organizations have developed social media platforms for specific collaborative projects. Tools like Basecamp and Podio provide social media interfaces for organizing project and event-

Content Communities

Content communities are the best examples of the many-

49

Social Networking Sites

Perhaps the most visible examples of social media are social networking sites like Facebook, LiveJournal, Pinterest, Orkut, LinkedIn, and Google+. On these sites, users can create content, share ideas, and interact with friends and colleagues.

Facebook is the most popular social media site on the Internet. Started at Harvard in 2004 as an online substitute to the printed facebooks the school created for incoming first-

In 2011, Google introduced Google+, a social networking interface designed to compete with Facebook. Google+ enables users to develop distinct “circles,” by dragging and dropping friends into separate groups, rather than having one long list of friends. In response, Facebook created new settings to enable users to control who sees their posts.

Virtual Game Worlds and Virtual Social Worlds

Virtual game worlds and virtual social worlds invite users to role-

Social Media and Democracy

In just a decade, social media have changed the way we consume and relate to media and the way we communicate with others. Social media tools have put unprecedented power in our hands to produce and distribute our own media. We can share our thoughts and opinions, write or update an encyclopedic entry, start a petition or fund-

The wave of protests in more than a dozen Arab nations in North Africa and the Middle East that began in late 2010 resulted in four rulers being forced from power by mid-

52

In Egypt, a similar circumstance occurred when twenty-

Even in the United States, social media have helped call attention to issues that might not have received any media attention otherwise. In 2011 and 2012, protesters in the Occupy Wall Street movement in New York and at hundreds of sites across the country took to Twitter, Tumblr, YouTube, and Facebook to point out the inequalities of the economy and the income disparity between the wealthiest 1 percent and the rest of the population—

The flexible and decentralized nature of the Internet and social media is in large part what makes them such powerful tools for subverting control. In China, the Communist Party has tightly controlled mass communication for decades. As more and more Chinese citizens take to the Internet, an estimated thirty thousand government censors monitor or even block Web pages, blogs, chat rooms, and e-

50

EXAMINING ETHICS

“Anonymous” Hacks Global Terrorism

S ince its earliest days, the Internet has been a medium for both good and evil. Among the most evil uses of the Internet are those emerging from the widely condemned terrorism group ISIS, which since 2014 has used the Internet to recruit naïve new members from around the world and to post videos of its massacres and gruesome beheadings of Westerners and other captives.

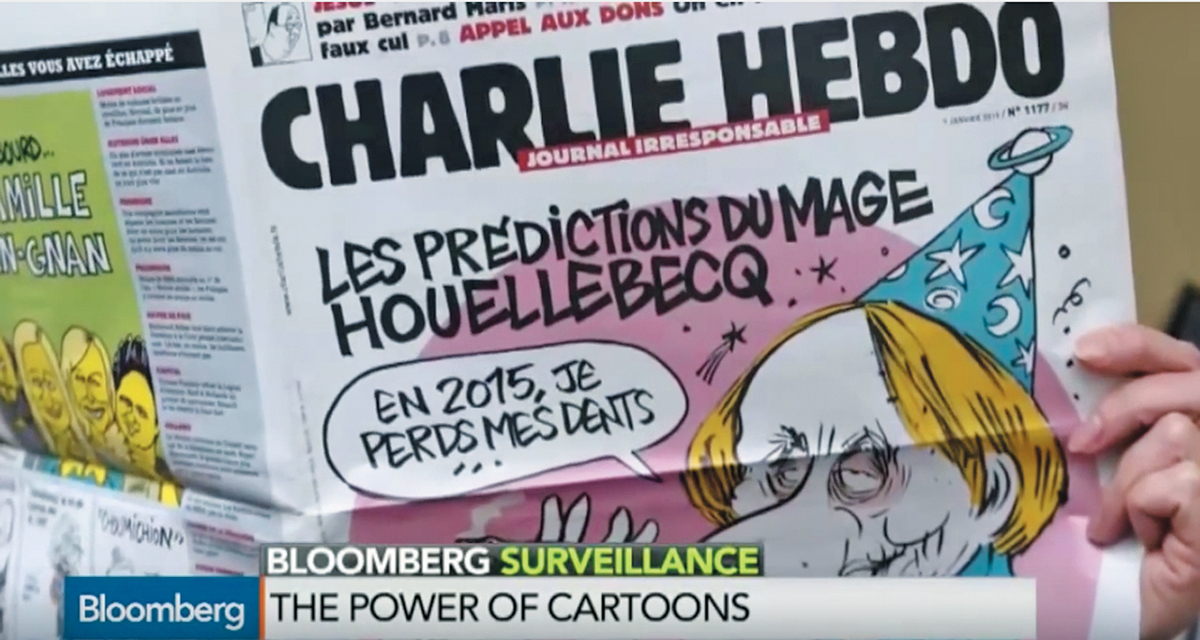

Given that, it was easy to cheer for Anonymous in 2015, when the loosely organized global hacktivist collective known for its politically and socially motivated Internet vigilantism decided to hack ISIS. The group vowed to avenge the January 2015 ISIS-

We are Muslims, Christians, Jews. We are hackers, crackers, hactivists, phishers, agents, spies, or just the guy from next door. . . . We come from all races, countries, religions, and ethnicities. United by one, divided by zero. We are Anonymous. Remember: The terrorists who are calling themselves Islamic State—

Although some argued that Anonymous shouldn’t involve itself in anti-

Anonymous first attracted major public attention in 2008. The issue was a video featuring a fervent Tom Cruise—

51

United by its libertarian distrust of government, its commitment to a free and open Internet, its opposition to child pornography, and its distaste for corporate conglomerates, Anonymous has targeted organizations as diverse as the Indian government (to protest the country’s plan to block Web sites like The Pirate Bay and Vimeo) and the agricultural conglomerate Monsanto (to protest the company’s malicious patent lawsuits and its dominant control of the food industry). While Anonymous agrees on an agenda and coordinates the campaign, the individual hackers all act independently of the group, without expecting recognition.

As with the #OpISIS campaign, it can often be easy to find the good in the activities of hacktivists. For example, Anonymous reportedly hacked the computer network of Tunisian tyrant Zine el-

But sometimes it is harder to tell whether Anonymous is virtuous or not. Because the members of Anonymous are indeed anonymous, there aren’t any checks or balances on those who “dox” a corporate site, revealing documents carrying personal credit card or social security numbers and making regular citizens vulnerable to identity theft and fraud, as some hackers have done. For example, prosecutions in 2012 took down at least six international members of Anonymous when one hacker, known online as Sabu, turned out to be a government informant. One of the hackers arrested in Chicago was charged with stealing credit card data and using it to make more than $700,000 in charges.4 Just a few “bad apples” can undermine the self-

The very existence of Anonymous is a sign that many of our battles now are in the digital domain. We fight for equal access and free speech on the Internet, we are in a perpetual struggle with corporations and other institutions over the privacy of our digital information, and, although our government prosecutes hackers for computer crimes, governments themselves are increasingly using hacking to fight one another. In the case of the Internet and ISIS, perhaps the U.S. government (although it might be loathe to admit it) secretly appreciates the work Anonymous does.

53