Chapter 1. LaunchPad for Media and Culture 11e

Fake News: An Updated Extended Case Study

Author Names:

Christopher R. Martin and Bettina Fabos

Activity Objective:

Students will learn about the history of fake news, and will then follow the steps of the critical process to examine and analyze coverage of a current major news event.

Let’s get started! Click the forward and backward arrows to navigate through the slides. You may also click the above outline button to skip to certain slides.

Fake News: An Updated Extended Case Study

Fake news, which has dominated the real news headlines since 2016 and is as prominent as ever in 2018, is unfortunately about as old as the United States itself. And it got its start, not surprisingly, in politics.

The presidential election of 1800 pitted two bitter rivals against each other: incumbent President John Adams of the Federalist Party (whose members included George Washington and Alexander Hamilton) and his challenger, Vice President Thomas Jefferson of the Democratic-Republican Party (whose members included James Madison and Aaron Burr).1

Many of America’s earliest newspapers were either the commercial press, which catered to the merchant class, or the partisan press, which fervidly argued for the platform of whichever political party subsidized the paper. You might guess that it was the partisan press that resorted to fake news. As the presidential campaign of 1800 grew more heated, some Federalist-funded newspapers began to publish stories that Jefferson had died.2 Eventually the truth came out—although at the slow pace of newspaper distribution at the time—and Jefferson ultimately won the election.

Unfortunately, both in 1800 and now, fake news can draw people in and then lead them down the wrong path. According to a 2018 study of fake news on Twitter by researchers at MIT, false news spreads faster than the truth. Unfortunately, many of us are the unwitting facilitators of fake news. “False news spreads more quickly than the truth because humans, not robots, are more likely to spread it. Falsehoods were 70% more likely to be retweeted than the truth.”3

The problem, researchers explain, is novelty. People like to share novel information and have little regard for whether or not it is true. Considering how rumors spread, it is easy to understand how fake news has circulated in human history long before the Internet was invented.

Although the United States has changed in many ways since the election of 1800, the fake news that stemmed from that time is still affecting both politics and society today. However, the specifics of what constitutes fake news have been muddled in a world where the President of the United States has been known to declare that any press he disagrees with is “fake news.” So, what exactly is fake news?

The 5 Categories

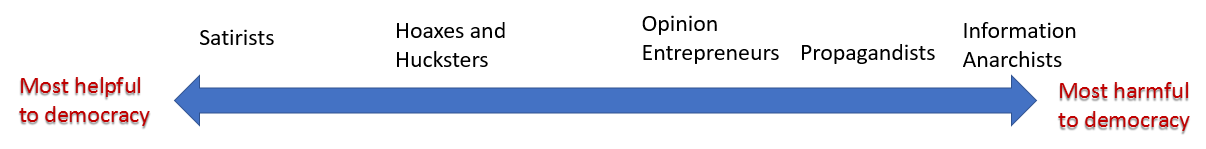

As we consider all of the stories identified as fake news, we can identify a phenomenon that spans five general categories of activity:

Satirists

This category includes the recent work of Saturday Night Live, The Daily Show with Jon Stewart (which Comedy Central promoted as “America’s Most Trusted Name in Fake News”), The Colbert Report, and The Onion. Satire wears its “fake news” badge openly. When done well, satire can also be extremely effective as a critical voice in the news.

Hoaxers and Hucksters

Hoaxers and hucksters, who create and distribute intentionally false news stories, are generally harmless (there is entertainment pleasure in having one’s gullibility tested), but they can also involve real harm, particularly with the financial hoaxes of Ponzi schemes, or more recently, Bernie Madoff.

Opinion Entrepreneurs

These are media outlets—from web sites and talk radio to newspapers and cable news that seek to influence the news and public agenda, often with false or inaccurate stories.4 The “birther” story questioning President Barack Obama’s national citizenship was (and for some, continues to be) a case of opinion entrepreneurialism, and it became a major news media story only after the continuing allegations of then-citizen Donald Trump and several birther Web sites.5

Propagandists

Propagandists are official state actors who spread a coordinated partisan message meant to propagate a point of view. Today’s North Korea, Iraq, China, and Russia would be the most easily identifiable propagandists, with a secure hold on major media outlets and a sophisticated system of news and media that supports the goals of their regimes.

Information Anarchists

Information anarchists are actors who want to stir the pot, make people angry with outrageous statements and allegations, and create doubt and mistrust (sometimes called “gaslighting”) to undermine the legitimacy of genuine news itself and to create the perception that the truth might never be determined. Internet trolls—people who post inflammatory or harassing messages and memes to elicit emotional reactions and sow discontent—are information anarchists.

The five types of fake news constitute a continuum, from most useful to democracy (satire) to most harmful to democracy (information anarchy).

Being a Critical Consumer

So, how do we, as critical consumers, decipher whether or not the news we’re reading is real or fake? And, when fake news is in play, how do we determine how harmful a particular piece of fake news might be to democracy?

As developed in Chapter 1, a media-literate perspective involves mastering five overlapping critical stages that build on one another: (1) description: paying close attention, taking notes, and researching the subject under study; (2) analysis: discovering and focusing on significant patterns that emerge from the description stage; (3) interpretation: asking and answering the “What does that mean?” and “So what?” questions about your findings; (4) evaluation: arriving at a judgment about whether something is good, bad, poor, or mediocre, which involves subordinating one’s personal views to the critical assessment resulting from the first three stages; and (5) engagement: taking some action that connects our critical interpretations and evaluations with our responsibility as citizens.

In the activity that follows, we will examine news stories from a recent major news event and evaluate the validity of the news coverage surrounding it.

Description

Use the space below to answer the following question.

As a class, select a major news event to examine. It should be an event with plenty of coverage from many different perspectives. Research at least five different news stories of this event, looking for some stories from reputable news organizations, such as the New York Times, and some from less-reputable organizations or Web sites. Using the box below, take notes about your research and your initial impressions.

Analysis

Use the space below to answer the following question.

Now we’re going to dig in to the five (or more) news stories you selected. What similarities and differences do you see as you analyze the stories? Do you see any patterns across the stories? In which of the five fake news categories does each story from a less-reputable source seem to fit? How easy is it for you to determine which articles are reputable and which are fake news?

Interpretation

Use the space below to answer the following question.

In stage three of the critical process, we’ll be interpreting the patterns that came out during the analysis stage. What story or stories are the reputable news organizations telling? Why?

Think about the “fake” news stories you found during your research. Are they telling a similar story or many different stories? What are the motivations of specific news organizations or Web sites for framing the story the way they did? Are they trying to be funny? Trying to influence a certain political group? Or just trying to confuse the news audience?

Evaluation

Use the space below to answer the following question.

In the evaluation stage, you’ll take all the work you did in the first three stages and make informed judgements. Consider the fake news stories you’ve read and the motivation behind each story. Consider the category of fake news each story falls into (satirists, hoaxes and hucksters, opinion entrepreneurs, propagandists, or information anarchists). Based on the category they fall in, how harmful might these particular news stories be to democracy? Why?

Engagement

Use the space below to answer the following question.

The fifth stage of the critical process encourages you to take action and use your voice for change. Using the knowledge you’ve gained during this activity, what can you do to help combat harmful fake news? Could you write a letter to the editor of a fake news site describing the research you have compiled against their argument? Or a letter to the editor of a great publication thanking them for telling the whole story? Could you spread awareness on social media, encouraging others to think critically about the type of news they’re consuming? Should you reconsider your own way of participating in “viral” stories on social media? What other ideas do you have?

Reading Fake News

In an era of fake news, there are new reasons for optimism: All around the globe, there is now high interest in how to recognize fake news.6

With so many forms of fake news in circulation, it might be helpful to be reminded of what real, genuine, authentic journalism does. Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel, in their classic The Elements of Journalism, spell out several important factors of good journalism. Perhaps the most important of these elements is: “Journalism’s first obligation is to truth; its first loyalty is to citizens; its essence is a discipline of verification; its practitioners must maintain and independence from those they cover; and it must serve as an independent monitor of power.”7

The best way to judge is to read/watch/listen to the news and test its adherence to these elements of journalism, which form the foundation of the “how to spot fake news” lists.

Notes

- The approval of the 12th Amendment the U.S. Constitution in 1804 later enabled presidential and vice-presidential candidates to run as a ticket, thus avoiding the awkward situation of Adams and Jefferson, where the elected president and vice-president were from opposing parties.

- "Fit to Print? A History of Fake News," Backstory, February 20, 2017, http://backstoryradio.org/shows/fit-to-print/.

- "The Truth About False News, MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy, March 8, 2018, http://ide.mit.edu/news-blog/news/truth-about-false-news.

- Peter Dreier and Christopher R. Martin, "How ACORN Was Framed: Political Controversy and Media Agenda Setting," Perspectives on Politics 8, no. 3 (2010), 761-792.

- Vincent N. Pham, "Our Foreign President Barack Obama: The Racial Logics of Birther Discourses," Journal of International And Intercultural Communication 8, no. 2 (2015), 86-107.

- See International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, "How To Spot Fake News," March 2, 2017, http://www.ifla.org/publications/node/11174; Eugene Kiely and Lori Robertson, "How to Spot Fake News," FactCheck.org, November 18, 2016, http://www.factcheck.org/2016/11/how-to-spot-fake-news/; Wynne Davis, "Fake Or Real? How To Self-Check The News And Get The Facts," NPR, December 5, 2016, http://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/12/05/503581220/fake-or-real-how-to-self-check-the-news-and-get-the-facts.

- Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel, The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2007).