Promoting Social Change and Dictating Values

As U.S. advertising became more pervasive, it contributed to major social changes in the twentieth century. First, it significantly influenced the transition from a producer-directed to a consumer-driven society. By stimulating demand for new products, advertising helped manufacturers create new markets and recover product start-up costs quickly. From farms to cities, advertising spread the word—first in newspapers and magazines and later on radio and television.

Second, advertising promoted technological advances by showing how new machines, such as vacuum cleaners, washing machines, and cars, could improve daily life. Third, advertising encouraged economic growth by increasing sales. To meet the demand generated by ads, manufacturers produced greater quantities, which reduced their costs per unit, although they did not always pass these savings along to consumers.

Appealing to Female Consumers

By the early 1900s, advertisers and ad agencies believed that women, who constituted 70 to 80 percent of newspaper and magazine readers, controlled most household purchasing decisions. (This is still a fundamental principle of advertising today.) Ironically, more than 99 percent of the copywriters and ad executives at that time were men, primarily based in Chicago and New York. They emphasized stereotyped appeals to women, believing that simple ads with emotional and even irrational content worked best. Thus early ad copy featured personal tales of “heroic” cleaning products and household appliances. The intention was to help female consumers feel good about defeating life’s problems—an advertising strategy that endured throughout much of the twentieth century.

Dealing with Criticism

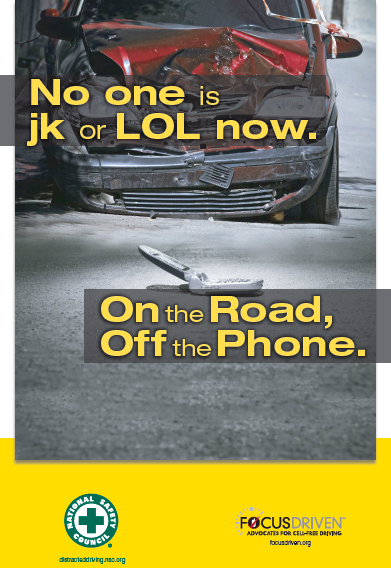

The Ad Council has been creating public service announcements (PSAs) since 1942. Supported by contributions from individuals, corporations, and foundations, the council’s PSAs are produced pro bono by ad agencies. This PSA is the result of the Ad Council’s long-standing relationship with the National Safety Council.

Although ad revenues fell during the Great Depression in the 1930s, World War II brought a rejuvenation in advertising. For the first time, the federal government bought large quantities of advertising space to promote U.S. involvement in a war. These purchases helped offset a decline in traditional advertising, as many industries had turned their attention and production facilities to the war effort.

Also during the 1940s, the industry began to actively deflect criticism that advertising created consumer needs that ordinary citizens never knew they had. Criticism of advertising grew as the industry appeared to be dictating values as well as driving the economy. To promote a more positive image, the industry developed the War Advertising Council—a voluntary group of agencies and advertisers that organized war bond sales, blood donor drives, and the rationing of scarce goods.

The postwar extension of advertising’s voluntary efforts became known as the Ad Council, praised over the years for its Smokey the Bear campaign (“Only you can prevent forest fires”); its fund-raising campaign for the United Negro College Fund (“A mind is a terrible thing to waste”); and its “crash dummy” spots for the Department of Transportation, which substantially increased seat belt use. Choosing a dozen worthy causes annually, the Ad Council continues to produce pro bono public service announcements (PSAs) on a wide range of topics, including literacy, homelessness, drug addiction, smoking, and AIDS education.