“Fake” News and Satiric Journalism

“There’s no journalist today, real or fake, who is more significant for people 18 to 25.”

SETH SIEGEL, ADVERTISING AND BRANDING CONSULTANT, TALKING ABOUT JON STEWART

For many young people, it is especially disturbing that two wealthy, established political parties—beholden to special interests and their lobbyists—control the nation’s government. After all, 98 percent of congressional incumbents get reelected each year—not always because they’ve done a good job but often because they’ve made promises and done favors for the lobbyists and interests that helped get them elected in the first place.

Why shouldn’t people, then, be cynical about politics? It is this cynicism that has drawn increasingly larger audiences to “fake” news shows like The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and The Colbert Report on cable’s Comedy Central. Following in the tradition of Saturday Night Live (SNL), which began in 1975, news satires tell their audiences something that seems truthful about politicians and how they try to manipulate media and public opinion. But most important, these shows use humor to critique the news media and our political system. SNL’s sketches on GOP vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin in 2008 drew large audiences and shaped the way younger viewers thought about the election.

The Colbert Report satirizes cable “star” news hosts, particularly Fox’s Bill O’Reilly and MSNBC’s Chris Matthews, and the bombastic opinion-assertion culture promoted by their programs. In critiquing the limits of news stories and politics, The Daily Show, “anchored” by Stewart, parodies the narrative conventions of evening news programs: the clipped eight-second “sound bite” that limits meaning and the formulaic shot of the TV news “stand up,” which depicts reporters “on location,” attempting to establish credibility by revealing that they were really there.

On The Daily Show, a cast of fake reporters are digitally superimposed in front of exotic foreign locales, Washington, D.C., or other U.S. locations. In a 2004 exchange with “political correspondent” Rob Corddry, Stewart asked him for his opinion about presidential campaign tactics. “My opinion? I don’t have opinions,” Corddry answered. “I’m a reporter, Jon. My job is to spend half the time repeating what one side says, and half the time repeating the other. Little thing called objectivity; might want to look it up.”

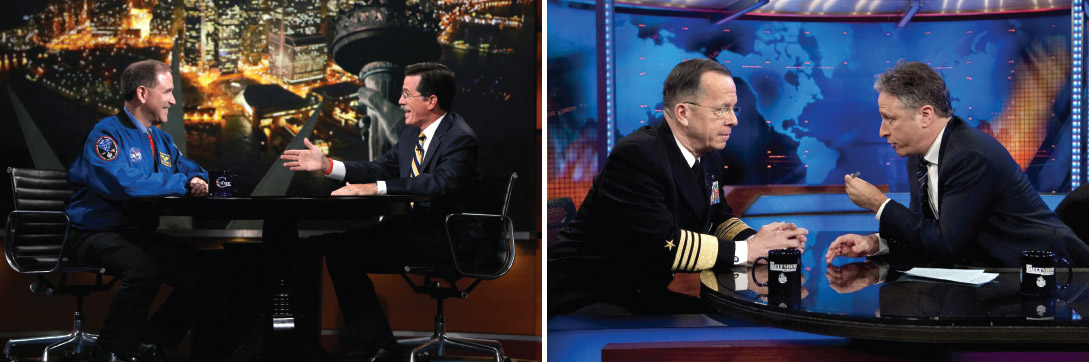

Political satirists Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert have welcomed a variety of political leaders and celebrity guests to their respective news shows, The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and The Colbert Report, throughout their time on-air. In 2012, Stewart interviewed President Obama for the sixth time, while Colbert welcomed First Lady Michelle Obama to his show a few months before the election. Here Stewart is shown interviewing Navy Admiral Mike Mullen, while Colbert is pictured with John Grunsfeld, Associate Administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate.

As news court jester, Stewart exposes the melodrama of TV news that nightly depicts the world in various stages of disorder while offering the stalwart, comforting presence of celebrity-anchors overseeing it all from their high-tech command centers. Even before CBS’s usually neutral and aloof Walter Cronkite signed off the evening news with “And that’s the way it is,” network news anchors tried to offer a sense of order through the reassurance of their individual personalities.

Yet even as a fake anchor, Stewart displays a much greater range of emotion—a range that may match our own—than we get from our detached “hard news” anchors: more amazement, irony, outrage, laughter, and skepticism. For example, during his program’s coverage of the 2012 presidential election, he would frequently show genuine irritation or even outrage—coupled with irony and humor—whenever a politician or political ad presented information that was untrue or misleading.

While Stewart often mocks the formulas that real TV news programs have long used, he also presents an informative and insightful look at current events and the way “traditional” media cover them. For example, he exposes hypocrisy by juxtaposing what a politician said recently in the news with the opposite position articulated by the same politician months or years earlier. Indeed, many Americans have admitted that they watch satires such as The Daily Show not only to be entertained but also to stay current with what’s going on in the world. In fact, a prominent Pew Research Center study in 2007 found that people who watched these satiric shows were more often “better informed” than most other news consumers, usually because these viewers tended to get their news from multiple sources and a cross-section of news media.46

Although the world has changed, local TV news story formulas (except for splashy opening graphics and Doppler weather radar) have gone virtually unaltered since the 1970s, when SNL’s “Weekend Update” first started making fun of TV news. Newscasts still limit reporters’ stories to two minutes or less and promote stylish anchors, a “sports guy,” and a certified meteorologist as familiar personalities whom we invite into our homes each evening. Now that a generation of viewers has been raised on the TV satire and political cynicism of “Weekend Update,” David Letterman, Jimmy Fallon, Conan O’Brien, The Daily Show, and The Colbert Report, the slick, formulaic packaging of political ads and the canned, cautious sound bites offered in news packages are simply not so persuasive.

Journalism needs to break free from tired formulas—especially in TV news—and reimagine better ways to tell stories. In fictional television, storytelling has evolved over time, becoming increasingly complex. Although the Internet and 24/7 cable have introduced new models of journalism and commentary, why has TV news remained virtually unchanged over the past forty years? Are there no new ways to report the news? Maybe audiences would value news that matches the complicated storytelling that surrounds them in everything from TV dramas to interactive video games to their own conversations. We should demand news story forms that better represent the complexity of our world.