Ethical Predicaments

What is the moral and social responsibility of journalists, not only for the stories they report but also for the actual events or issues they are shaping for millions of people? Wrestling with such media ethics involves determining the moral response to a situation through critical reasoning. Although national security issues raise problems for a few of our largest news organizations, the most frequent ethical dilemmas encountered in most newsrooms across the United States involve intentional deception, privacy invasions, and conflicts of interest.

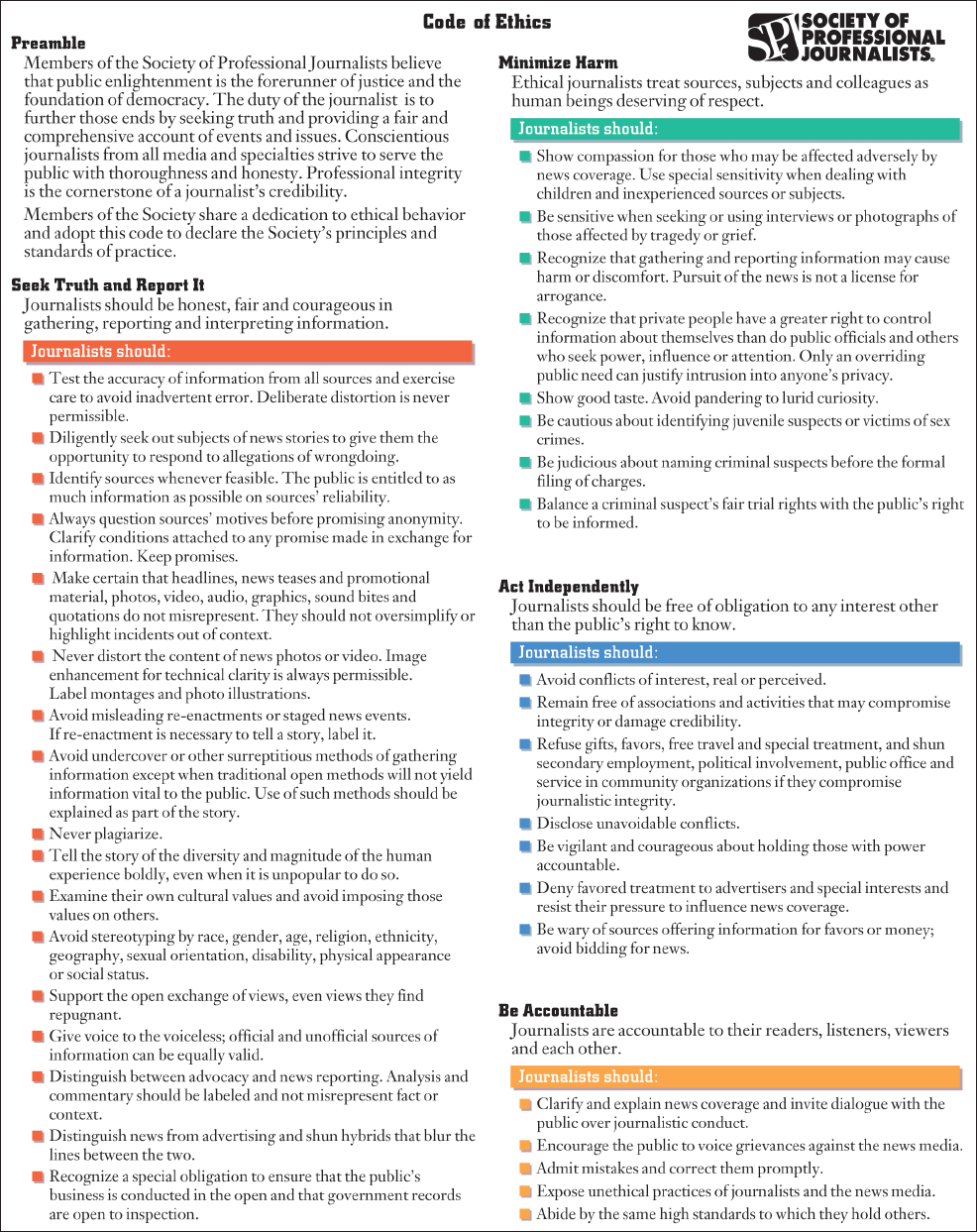

Source: Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ).

Deploying Deception

Ever since Nellie Bly faked insanity to get inside an asylum in the 1880s, investigative journalists have used deception to get stories. Today, journalists continue to use disguises and assume false identities to gather information on social transgressions. Beyond legal considerations, though, a key ethical question comes into play: Does the end justify the means? For example, can a newspaper or TV newsmagazine use deceptive ploys to go undercover and expose a suspected fraudulent clinic that promises miracle cures at a high cost? Are news professionals justified in posing as clients desperate for a cure?

In terms of ethics, there are at least two major positions and multiple variations. First, absolutist ethics suggests that a moral society has laws and codes, including honesty, that everyone must live by. This means citizens, including members of the news media, should tell the truth at all times and in all cases. In other words, the ends (exposing a phony clinic) never justify the means (using deception to get the story). An editor who is an absolutist would cover this story by asking a reporter to find victims who have been ripped off by the clinic, telling the story through their eyes. At the other end of the spectrum is situational ethics, which promotes ethical decisions on a case-by-case basis. If a greater public good could be served by using deceit, journalists and editors who believe in situational ethics would sanction deception as a practice.

Should a journalist withhold information about his or her professional identity to get a quote or a story from an interview subject? Many sources and witnesses are reluctant to talk with journalists, especially about a sensitive subject that might jeopardize a job or hurt another person’s reputation. Journalists know they can sometimes obtain information by posing as someone other than a journalist, such as a curious student or a concerned citizen.

Most newsrooms frown on such deception. In particular situations, though, such a practice might be condoned if reporters and their editors believed that the public needed the information. The ethics code adopted by the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) is fairly silent on issues of deception. The code “requires journalists to perform with intelligence, objectivity, accuracy, and fairness,” but it also says that “truth is our ultimate goal.” (See Figure 14.1, “SPJ Code of Ethics,”.)

Invading Privacy

“In the era of YouTube, Twitter and 24-hour cable news, nobody is safe.”

VAN JONES, FORMER SPECIAL ADVISOR TO THE OBAMA ADMINISTRATION ON ENVIRONMENTAL JOBS, WHO WAS FORCED TO RESIGN IN 2009 BECAUSE OF HIS PAST CRITICISMS OF REPUBLICAN LEADERS THAT SURFACED ON TV AND TALK RADIO

To achieve “the truth” or to “get the facts,” journalists routinely straddle a line between “the public’s right to know” and a person’s right to privacy. For example, journalists may be sent to hospitals to gather quotes from victims who have been injured. Often there is very little the public might gain from such information, but journalists worry that if they don’t get the quote, a competitor might. In these instances, have the news media responsibly weighed the protection of individual privacy against the public’s right to know? Although the latter is not constitutionally guaranteed, journalists invoke the public’s right to know as justification for many types of stories.

One infamous example is the recent phone hacking scandal involving News Corp.’s now-shuttered U.K. newspaper, News of the World. In 2011, the Guardian reported that News of the World reporters had hired a private investigator to hack into the voice mail of thirteen-year-old murder victim Milly Dowler and had deleted some messages. Although there had been past allegations of reporters from News of the World hacking into the private voice mails of the British royal family, government officials, and celebrities, this revelation on the extent of News of the World’s phone hacking activities caused a huge scandal and led to the arrests and resignations of several senior executives. Today, in the digital age, when reporters can gain access to private e-mail messages, Twitter accounts, and Facebook pages as well as voice mail, such practices raise serious questions about how far a reporter should go to get information.

In the case of privacy issues, media companies and journalists should always ask the ethical questions: What public good is being served here? What significant public knowledge will be gained through the exploitation of a tragic private moment? Although journalism’s code of ethics says, “The news media must guard against invading a person’s right to privacy,” this clashes with another part of the code: “The public’s right to know of events of public importance and interest is the overriding mission of the mass media.”20 When these two ethical standards collide, should journalists err on the side of the public’s right to know?

Conflict of Interest

Journalism’s code of ethics also warns reporters and editors not to place themselves in positions that produce a conflict of interest—that is, any situation in which journalists may stand to benefit personally from stories they produce. “Gifts, favors, free travel, special treatment or privileges,” the code states, “can compromise the integrity of journalists and their employers. Nothing of value should be accepted.”21 Although small newspapers with limited resources and poorly paid reporters might accept such “freebies” as game tickets for their sportswriters and free meals for their restaurant critics, this practice does increase the likelihood of a conflict of interest that produces favorable or uncritical coverage.

On a broader level, ethical guidelines at many news outlets attempt to protect journalists from compromising positions. For instance, in most cities, U.S. journalists do not actively participate in politics or support social causes. Some journalists will not reveal their political affiliations, and some even decline to vote.

For these journalists, the rationale behind their decisions is straightforward: Journalists should not place themselves in a situation in which they might have to report on the misdeeds of an organization or a political party to which they belong. If a journalist has a tie to any group, and that group is later suspected of involvement in shady or criminal activity, the reporter’s ability to report on that group would be compromised—along with the credibility of the news outlet for which he or she works. Conversely, other journalists believe that not actively participating in politics or social causes means abandoning their civic obligations. They believe that fairness in their reporting, not total detachment from civic life, is their primary obligation.

In the digital age, conflict of interest cases surrounding opinion blogging have grown more complicated, especially when those opinion blogs run under the banner of traditional news media. For example, in 2010 David Weigel, whom the Washington Post hired to blog about the conservative movement, was forced to resign after private e-mails and Listserv messages were exposed in which he had used inflammatory rhetoric to vent about well-known conservatives like Matt Drudge, Ron Paul, and Rush Limbaugh. A Post editor commented at the time, “We can’t have any tolerance for the perception that people are conflicted or bring a bias to their work. … There’s abundant room on our Web site for a wide range of viewpoints, and we should be transparent about everybody’s viewpoint.”22 Critics afterward noted that mainstream news media sites should make clear to their readers whether the bloggers are actually opinion writers or professional journalists trying to write fairly on subjects about which they may not agree. In this case, Weigel’s credibility regarding his ability to blog fairly about right-wing politicians and pundits was compromised when his personal exchanges ridiculing conservatives came to light. This case illustrates the increasingly blurry line between the old journalism of verification and the new journalism of assertion.