Social and Political Pressures on the Movies

During the early part of the twentieth century, movies rose in popularity among European immigrants and others from modest socioeconomic groups. This, in turn, spurred the formation of censorship groups, which believed that the movies would undermine morality. During this time, according to media historian Douglas Gomery, criticism of movies converged on four areas: “the effects on children, the potential health problems, the negative influences on morals and manners, and the lack of a proper role for educational and religious institutions in the development of movies.”16

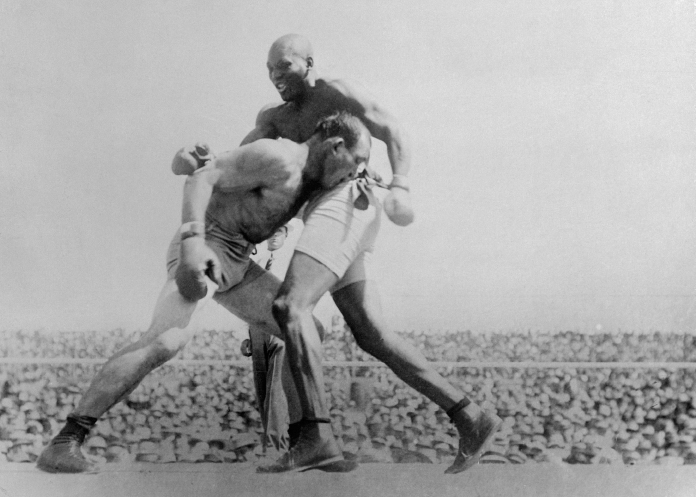

A native of Galveston, Texas, Jack Johnson (1878±1946) was the first black heavyweight boxing champion, from 1908 to 1914. His stunning victory over white champion Jim Jeffries (who had earlier refused to fight black boxers) in 1910 resulted in race riots across the country and led to a ban on the interstate transportation of boxing films. A 2005 Ken Burns documentary, Unforgivable Blackness, chronicles Johnson’s life.

Public pressure on movies came both from conservatives, who saw them as a potential threat to the authority of traditional institutions, and from progressives, who worried that children and adults were more attracted to movie houses than to social organizations and urban education centers. As a result, civic leaders publicly escalated their pressure, organizing local review boards that screened movies for their communities. In 1907, the Chicago City Council created an ordinance that gave the police authority to issue permits for the exhibition of movies. By 1920, more than ninety cities in the United States had some type of movie censorship board made up of vice squad officers, politicians, or citizens. By 1923, twenty-two states had established such boards.

Meanwhile, social pressure began to translate into law as politicians, wanting to please their constituencies, began to legislate against films. Support mounted for a federal censorship bill. When Jack Johnson won the heavyweight championship in 1908, boxing films became the target of the first federal censorship law aimed at the motion-picture industry. In 1912, the government outlawed the transportation of boxing movies across state lines. The laws against boxing films, however, had more to do with Johnson’s race than with concern over violence in movies. The first black heavyweight champion, he was perceived as a threat to some in the white community.

The first Supreme Court decision regarding film’s protection under the First Amendment was handed down in 1915 and went against the movie industry. In Mutual v. Ohio, the Mutual Film Company of Detroit sued the state of Ohio, whose review board had censored a number of the distributor’s films. On appeal, the case arrived at the Supreme Court, which unanimously ruled that motion pictures were not a form of speech but “a business pure and simple” and, like a circus, merely a “spectacle” for entertainment with “a special capacity for evil.” This ruling would stand as a precedent for thirty-seven years, although a movement to create a national censorship board failed.