Introduction

| 1 |

| Mass Communication: A Critical Approach |

“Some billionaires like cars, yachts and private jets. Others like newspapers.”

–COLUMNIST ANDREW ROSS SORKIN ON THE BEZOS DEAL, NEW YORK TIMES, AUGUST 2013

6 Culture and the Evolution of Mass Communication

10 The Development of Media and Their Role in Our Society

17 Surveying the Cultural Landscape

30 Critiquing Media and Culture

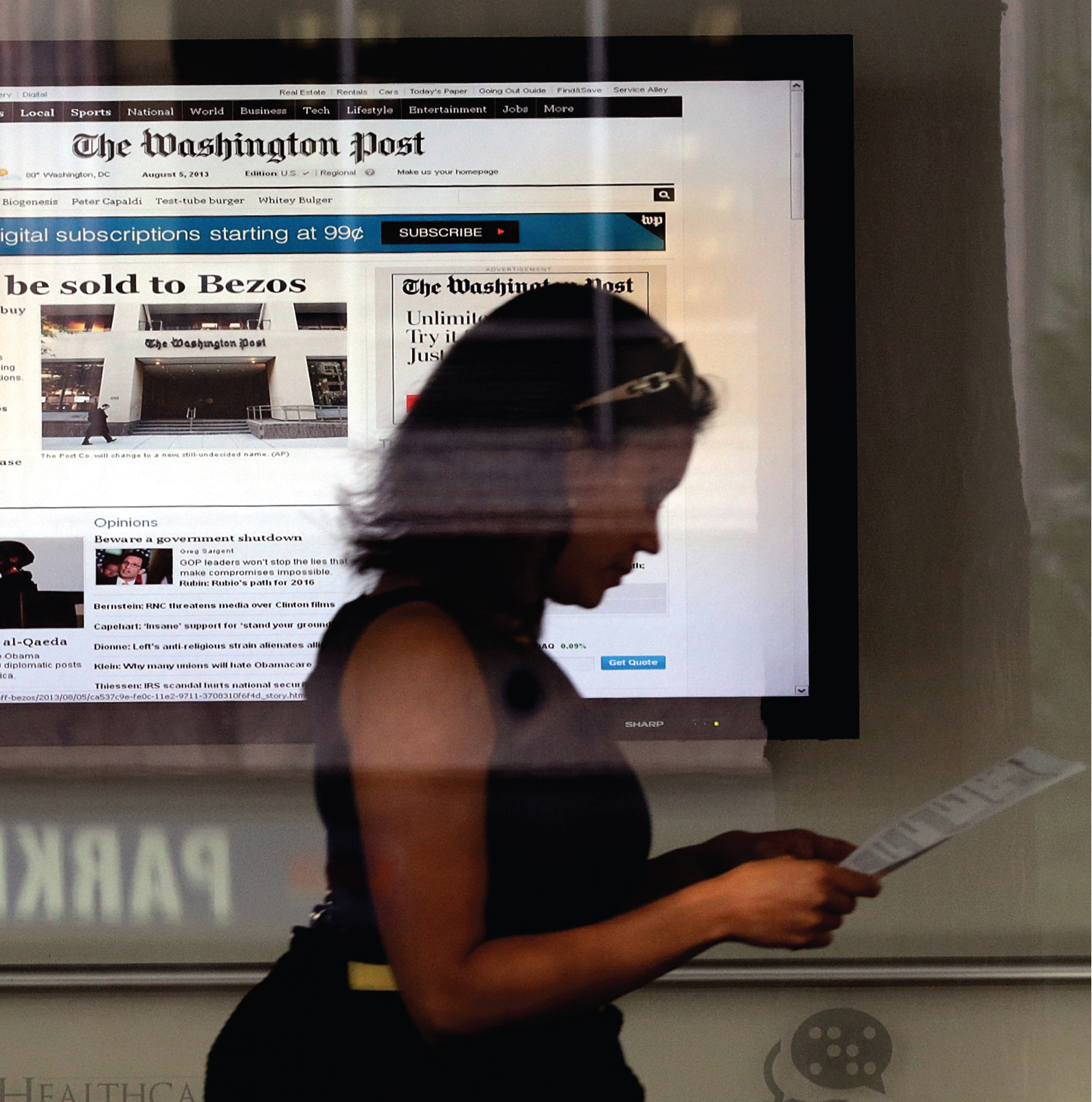

In August 2013, Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon.com, plunked down $250 million of his own money and bought the 135-year-old Washington Post, a journalistic institution whose legacy includes historic investigative reporting on the Watergate scandal that ended the Nixon presidency. The purchase was a symbolic shift of sorts—a major New Media player buying a dying Old Media icon. The daily circulation for the storied Post had peaked back in 1993 at 832,000 and had fallen to 474,000 by 2013; the paper had lost $53.7 million in 2012 and another $49 million in the first half of 2013.1 At the time of the purchase, Bezos wrote: “The Internet is transforming almost every element of the news business: shortening news cycles, eroding long-reliable revenue sources, and enabling new kinds of competition, some of which bear little or no news-gathering costs. There is no map, and charting a path ahead will not be easy. We will need to invent, which means we will need to experiment.”2 It sounded like Bezos was up for an adventure—one that may lead to an inventive new way of doing business for an old conventional medium.

Many economists and media watchers seemed baffled that a smart investor would bet on old print media in a digital age. But this convergence of print and digital media does have some precedents. Amazon used the book—the world’s oldest mass medium—as the primary initial offering for what would become the world’s largest online retailer, offering everything from appliances to watches. Bezos also seemed to follow the lead of investing wizards like Warren Buffett, who bought twenty-eight papers in 2012 and kept buying them in 2013 (see Chapter 8). On that same weekend that Bezos bought the Post, hedge fund investor and Boston Red Sox owner John Henry paid $70 million for the Boston Globe, a paper that the New York Times Company bought in 1993 for $1.1 billion.

What sets Amazon’s newspaper purchase apart is the willingness of Bezos and his company to step into the content and story creation business, similar to their move into original TV programming for their online streaming network. In our digital era, people still want information and stories, and newspapers have long been in the storytelling and information-gathering business—giving them a competitive edge. Indeed, Warren Buffett has discussed his views on the importance of news: “Newspapers continue to reign supreme … in the delivery of local news. If you want to know what’s going on in your town—whether the news is about the mayor or taxes or high school football—there is no substitute for a local newspaper that is doing its job.”3

Despite the limitations of our various media, that job of presenting our local communities and the world to us–documenting what’s going on—is enormously important. But we also have an equally important job to do. We must point a critical lens back at the media and describe, analyze, and interpret the information and stories we find, and then arrive at informed judgments about the media’s performance. This textbook offers a map to help us become more media literate, critiquing the media not as detached cynics watching billionaires buy up old media but as informed audiences with a big stake in the outcome.

SO WHAT EXACTLY ARE THE RESPONSIBILITIES OF NEWSPAPERS AND MEDIA IN GENERAL?In an age of highly partisan politics, economic and unemployment crises, and upheaval in several Arab nations, how do we demand the highest standards from our media to describe and analyze such complex events and issues—especially at a time when the business models for newspapers and most other media are in such flux? At their best, in all their various forms, from mainstream newspapers and radio talk shows to blogs, the media try to help us understand the events that affect us. But, at their worst, the media’s appetite for telling and selling stories leads them not only to document tragedy but also to misrepresent or exploit it. Many viewers and critics disapprove of how media, particularly TV and cable, hurtle from one event to another, often dwelling on trivial, celebrity-driven content.

SO WHAT EXACTLY ARE THE RESPONSIBILITIES OF NEWSPAPERS AND MEDIA IN GENERAL?In an age of highly partisan politics, economic and unemployment crises, and upheaval in several Arab nations, how do we demand the highest standards from our media to describe and analyze such complex events and issues—especially at a time when the business models for newspapers and most other media are in such flux? At their best, in all their various forms, from mainstream newspapers and radio talk shows to blogs, the media try to help us understand the events that affect us. But, at their worst, the media’s appetite for telling and selling stories leads them not only to document tragedy but also to misrepresent or exploit it. Many viewers and critics disapprove of how media, particularly TV and cable, hurtle from one event to another, often dwelling on trivial, celebrity-driven content.

In this book, we examine the history and business of mass media, and discuss the media as a central force in shaping our culture and our democracy. We start by examining key concepts and introducing the critical process for investigating media industries and issues. In later chapters, we probe the history and structure of media’s major institutions. In the process, we will develop an informed and critical view of the influence these institutions have had on national and global life. The goal is to become media literate—to become critical consumers of mass media institutions and engaged participants who accept part of the responsibility for the shape and direction of media culture. In this chapter, we will:

- Address key ideas including communication, culture, mass media, and mass communication

- Investigate important periods in communication history: the oral, written, print, electronic, and digital eras

- Examine the development of a mass medium from emergence to convergence

- Learn about how convergence has changed our relationship to media

- Look at the central role of storytelling in media and culture

- Discuss two models for organizing and categorizing culture: a skyscraper and a map

- Trace important cultural values in both the modern and postmodern societies

- Study media literacy and the five stages of the critical process: description, analysis, interpretation, evaluation, and engagement

As you read through this chapter, think about your early experiences with the media. Identify a favorite media product from your childhood—a song, book, TV show, or movie. Why was it so important to you? How much of an impact did your early taste in media have on your identity? How has your taste shifted over time to today? What does this change indicate about your identity now? For more questions to help you think about the role of media in your life, see “Questioning the Media” in the Chapter Review.

Past-Present-Future: The “Mass” Media Audience

In the sixties, seventies, and eighties—the height of the TV Network Era—people watched many of the same programs, like the Beverly Hillbillies, All in the Family, the Cosby Show, or the evening network news. But today, things have changed—especially for younger people. While almost all U.S. college students use Facebook or Twitter every day, they are rarely posting or reading about the same news or shared experiences.

In a world where we can so easily customize our media use, the notion of truly “mass” media may no longer exist. Today’s media marketplace is a fragmented world with more options than ever. Prime-time network TV has lost half its viewers in the last decade to the Internet and to hundreds of alternative channels. Traditional newspaper readership, too, continues to decline as young readers embrace social media, blogs, and their smartphones.

The former mass audience is morphing into individual users who engage with ever-narrowing politics, hobbies, and entertainment. As a result, media outlets that hope to survive must appeal not to mass audiences but to niche groups—whether these are conservatives, progressives, sports fans, history buffs, or reality TV addicts. But what does it mean for us as individuals with civic obligations to a larger society if we are tailoring media use and consumption so that we only engage with Facebook friends who share similar lifestyles, only visit media sites that affirm our personal interests, or only follow political blogs that echo our own views?