The Power of Media Stories in Everyday Life

The earliest debates, at least in Western society, about the impact of cultural narratives on daily life date back to the ancient Greeks. Socrates, himself accused of corrupting young minds, worried that children exposed to popular art forms and stories “without distinction” would “take into their souls teachings that are wholly opposite to those we wish them to be possessed of when they are grown up.”12 He believed art should uplift us from the ordinary routines of our lives. The playwright Euripides, however, believed that art should imitate life, that characters should be “real,” and that artistic works should reflect the actual world—even when that reality is sordid.

In The Republic, Plato developed the classical view of art: It should aim to instruct and uplift. He worried that some staged performances glorified evil and that common folk watching might not be able to distinguish between art and reality. Aristotle, Plato’s student, occupied a middle ground in these debates, arguing that art and stories should provide insight into the human condition but should entertain as well.

The cultural concerns of classical philosophers are still with us. In the early 1900s, for example, newly arrived immigrants to the United States who spoke little English gravitated toward cultural events (such as boxing, vaudeville, and the emerging medium of silent film) whose enjoyment did not depend solely on understanding English. Consequently, these popular events occasionally became a flash point for some groups, including the Daughters of the American Revolution, local politicians, religious leaders, and police vice squads, who not only resented the commercial success of immigrant culture but also feared that these “low” cultural forms would undermine what they saw as traditional American values and interests.

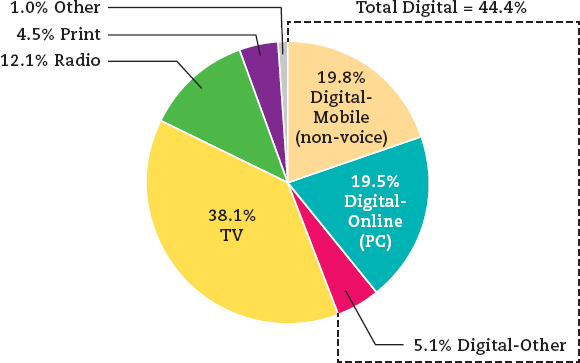

DAILY MEDIA CONSUMPTION BY PLATFORM, 2013

Source: “Media Consumption Estimates: Mobile > PC; Digital > TV,”Marketing Charts, www.marketingcharts.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/eMarketer-Share-Media-Consumption-by-Medium-2010-2013-Aug2013.png.

In the United States in the 1950s, the emergence of television and rock and roll generated several points of contention. For instance, the phenomenal popularity of Elvis Presley set the stage for many of today’s debates over hip-hop lyrics and television’s influence, especially on young people. In 1956 and 1957, Presley made three appearances on the Ed Sullivan Show. The public outcry against Presley’s “lascivious” hip movements was so great that by the third show the camera operators were instructed to shoot the singer only from the waist up. In some communities, objections to Presley were motivated by class bias and racism. Many white adults believed that this “poor white trash” singer from Mississippi was spreading rhythm and blues, a “dangerous” form of black popular culture.

Today, with the reach of print, electronic, and digital communications and the amount of time people spend consuming them (see Figure 1.1), mass media play an even more controversial role in society. Many people are critical of the quality of much contemporary culture and are concerned about the overwhelming amount of information now available. Many see popular media culture as unacceptably commercial and sensationalistic. Too many talk shows exploit personal problems for commercial gain, reality shows often glamorize outlandish behavior and sometimes dangerous stunts, and television research continues to document a connection between aggression in children and violent entertainment programs or video games. Children, who watch nearly forty thousand TV commercials each year, are particularly vulnerable to marketers selling junk food, toys, and “cool” clothing. Even the computer, once heralded as an educational salvation, has created confusion. Today, when kids announce that they are “on the computer,” many parents wonder whether they are writing a term paper, playing a video game, chatting on Facebook, or peering at pornography.

Yet how much the media shape society—and how much they simply respond to existing cultural issues—is still unknown. Although some media depictions may worsen social problems, research has seldom demonstrated that the media directly cause our society’s major afflictions. For instance, when a middle-school student shoots a fellow student over designer clothing, should society blame the ad that glamorized clothes and the network that carried the ad? Or are parents, teachers, and religious leaders failing to instill strong moral values? Or are economic and social issues involving gun legislation, consumerism, and income disparity at work as well? Even if the clothing manufacturer bears responsibility as a corporate citizen, did the ad alone bring about the tragedy, or is the ad symptomatic of a larger problem?

With American mass media industries earning more than $200 billion annually, the economic and societal stakes are high. Large portions of media resources now go toward studying audiences, capturing their attention through stories, and taking their consumer dollars. To increase their revenues, media outlets try to influence everything from how people shop to how they vote. Like the air we breathe, the commercially based culture that mass media help create surrounds us. Its impact, like the air, is often taken for granted. But to monitor that culture’s “air quality”—to become media literate—we must attend more thoughtfully to diverse media stories that are too often taken for granted. (For further discussion, see “Examining Ethics: Covering War”)