Making, Selling, and Profiting from Music

Like most mass media, the music business is divided into several areas, each working in a different capacity. In the music industry, those areas are making the music (signing, developing, and recording the artist), selling the music (selling, distributing, advertising, and promoting the music), and sharing the profits. All of these areas are essential to the industry but have always shared in the conflict between business concerns and artistic concerns.

Making the Music

Labels are driven by A&R (artist & repertoire) agents, the talent scouts of the music business, who discover, develop, and sometimes manage artists. A&R executives scan online music sites and listen to demonstration tapes, or demos, from new artists and decide whom to sign and which songs to record. A&R executives naturally look for artists who they think will sell, and they are often forced to avoid artists with limited commercial possibilities or to tailor artists to make them viable for the recording studio.

A typical recording session is a complex process that involves the artist, the producer, the session engineer, and audio technicians. In charge of the overall recording process, the producer handles most nontechnical elements of the session, including reserving studio space, hiring session musicians (if necessary), and making final decisions about the sound of the recording. The session engineer oversees the technical aspects of the recording session, everything from choosing recording equipment to managing the audio technicians. Most popular records are recorded part by part. Using separate microphones, the vocalists, guitarists, drummers, and other musical sections are digitally recorded onto separate audio tracks, which are edited and remixed during postproduction and ultimately mixed down to a two-track stereo master copy for reproduction to CD or online digital distribution.

Selling the Music

Selling and distributing music is a tricky part of the business. For years, the primary sales outlets for music were direct-retail record stores (independents or chains such as the now-defunct Sam Goody) and general retail outlets like Walmart, Best Buy, and Target. Such direct retailers could specialize in music, carefully monitoring new releases and keeping large, varied inventories. But as digital sales climbed, CD sales fell, hurting direct retail sales considerably. In 2006, Tower Records declared bankruptcy, closed its retail locations, and became an online-only retailer. Sam Goody stores were shuttered in 2008, and Virgin closed its last U.S. megastore in 2009. Meanwhile, other independent record stores either went out of business or experienced great losses, and general retail outlets began to offer considerably less variety, stocking only top-selling CDs.

At the same time, digital sales have grown to capture 50 percent of the U.S. market and 32 percent of the global market.19 Apple’s iTunes now sells songs at prices ranging from $0.69 to $1.49. It has become the leading music retailer, selling 38.2 percent of all music purchased in the United States. (See “What Apple Owns” at right.) Anderson Merchandisers, the behind-the-scenes wholesaler that stocks and manages music inventories at Walmart and Best Buy, is the second biggest music seller, at about 18 percent of the market, followed by Amazon (which also sells digital downloads) in third place, with 8 percent of the market. Alliance Entertainment, a wholesaler that manages and ships recorded music for several hundred online stores, is fourth, with a 6 percent market share.20

Dividing the Profits

VideoCentral  Mass Communication bedfordstmartins.com/mediaculture

Mass Communication bedfordstmartins.com/mediaculture

Alternative Strategies for Music Marketing

This video explores the strategies independent artists and marketers now employ to reach audiences.

Discussion: Even with the ability to bypass major record companies, many of the most popular artists still sign with those companies. Why do you think that is?

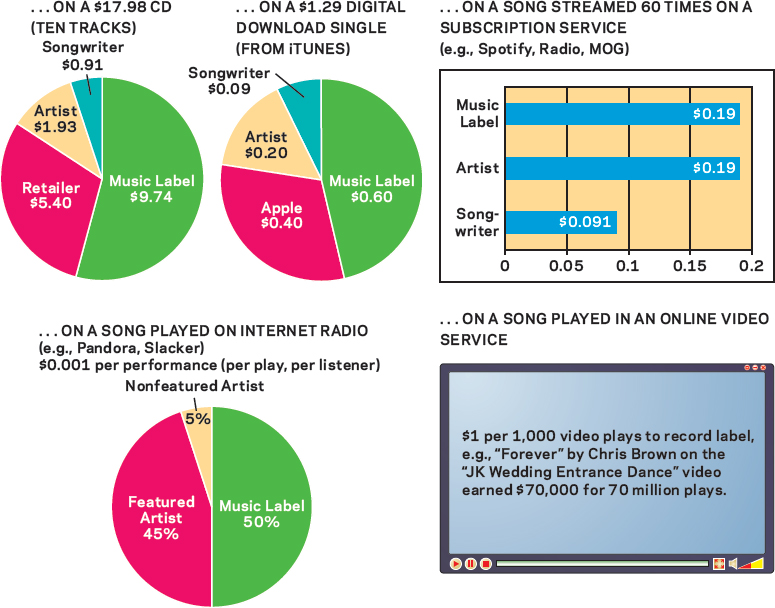

The upheaval in the music industry in recent years has shaken up the once predictable sale of music through CDs. Now there are multiple digital venues for selling music.24 But for the sake of example, we will first look at the various costs and profits from a typical CD that retails at $17.98. The wholesale price for that CD is about $12.50, leaving the remainder as retail profit. Discount retailers like Walmart and Best Buy sell closer to the wholesale price to lure customers to buy other things (even if they make less profit on the CD itself). The wholesale price represents the actual cost of producing and promoting the recording, plus the recording label’s profits. The record company reaps the highest revenue (close to $9.74 on a typical CD) but, along with the artist, bears the bulk of the expenses: manufacturing costs, packaging and CD design, advertising and promotion, and artists’ royalties (see Figure 4.3). The physical product of the CD itself costs less than a quarter to manufacture.

New artists usually negotiate a royalty rate of between 8 and 12 percent on the retail price of a CD, while more established performers might negotiate for 15 percent or higher. An artist who has negotiated a typical 11 percent royalty rate would earn about $1.93 per CD whose suggested retail price is $17.98. So a CD that “goes gold”—that is, sells 500,000 units—would net the artist around $965,000. But out of this amount, artists must repay the record company the money they have been advanced (from $100,000 to $500,000). And after band members, managers, and attorneys are paid with the remaining money, it’s quite possible that an artist will end up with almost nothing—even after a certified gold CD. (See “Case Study: In the Jungle, the Unjust Jungle, a Small Victory”.) The financial risk is much lower for the songwriter/publisher, who makes a standard mechanical royalty rate of about 9.1 cents per song, or $0.91 for a ten-song CD, without having to bear any production or promotional costs.

The profits are divided somewhat differently in digital download sales. A $1.29 iTunes download generates about $0.40 for iTunes (iTunes gets 30 percent of every song sale) and a standard $0.09 mechanical royalty for the song publisher and writer, leaving about $0.60 for the record company. Artists at a typical royalty rate of about 15 percent would get $0.20 from the song download. With no CD printing and packaging costs, record companies can retain more of the revenue on download sales.

Source: Steve Knopper, “The New Economics of the Music Industry,” Rolling Stone, October 25, 2011, http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/the-new-economics-of-the-music-industry-2011025.

Another venue for digital music is streaming services like Spotify, MOG, and Rdio. A single stream isn’t worth much, but collectively, they generate more substantial revenue. A song streamed sixty times is about the equivalent of one download and generates about $0.38 for the label and the artist, who—depending on the contract—typically split this 50–50.

Songs played on Internet radio, like Pandora, Slacker, or iHeartRadio, have yet another formula for determining royalties. In 2000, the nonprofit group SoundExchange was established to collect royalties for Internet radio. (The significant difference between Internet radio and subscription streaming services is that on Internet radio, listeners can’t select specific songs to play. Instead, Internet stations have “theme” stations.) SoundExchange charges fees of $0.002 per play, per listener. Large Internet radio stations can pay up to 25 percent of their gross revenue (less for smaller Internet radio stations, and a small flat fee for streaming nonprofit stations). About 50 percent of the fees go to the music label, 45 percent goes to the featured artists, and 5 percent goes to nonfeatured artists.

Finally, video services like YouTube and Vevo have become sites to generate advertising revenue through music videos, which can attract tens of millions of views. For example, OK Go’s video for “Needing/Getting” in 2012 drew more than twenty-one million views in just a few months. Even popular amateur videos that use copyrighted music can create substantial revenue for music labels and artists. The 2009 amateur video “JK Wedding Entrance Dance” (reprised in a wedding scene in TV’s The Office) has more than eighty-two million views. Instead of asking YouTube to remove the wedding video for its unauthorized use of Chris Brown’s song “Forever,” Sony licensed the video to stay on YouTube. At the rate of $1 per thousand video plays, it ultimately generated over $70,000 in ad revenue.

There aren’t standard formulas for sharing ad revenue from music videos, but there is movement in that direction. In 2012, Universal Music Group and the National Music Publishers Association agreed that music publishers would be paid 15 percent of advertising revenues generated by music videos licensed for use on YouTube and Vevo.

In addition to the top music retailers who sell digital downloads and physical CDs, subscription music streaming services like Rhapsody, Spotify, MOG, and Rdio are a small but growing market that can also generate revenue for music labels and their artists. But some leading artists—including Adele, the Black Keys, and Coldplay—have held back their new releases from such services due to concerns that streaming eats into their digital download and CD sales. “Part of the reason is that a song has to be played between 100 and 150 times on a streaming service in order to generate the same licensing revenue as a single download sale,” the Los Angeles Times reported.21 Yet, a later analysis by the same newspaper suggested there isn’t a clear relationship between streaming activity and digital download sales.22

Some established rock acts like Nine Inch Nails and Amanda Palmer are taking the “alternative” approach to their business model, shunning major labels and using the Internet to directly reach their fans. By selling music online at their own Web sites or CDs at live concerts, music acts generally do better, cutting out the retailer and keeping more of the revenue themselves.

Legitimate online music sales are now a growing success, and in 2011 the music industry recorded its first year of growth since 2004. Although online piracy—unauthorized online file sharing—is still a problem, with about one-quarter of Internet users worldwide accessing unauthorized music content each month, the international recording industry group IPFI reported in 2012 that “we are undoubtedly making important progress” toward “developing a sustainable legitimate digital music sector.” There are now about five hundred legal online music services worldwide.23

WHAT APPLE OWNS

Consider how Apple connects to your life; turn the page for the bigger picture.

ELECTRONICS

- iPod

- iPod Classic

- iPod Nano

- iPod Shuffle

- iPod Touch

- iPhone

- iPad

- Apple TV

- iMac

- MacBook Air

- MacBook Pro

- Mac Mini

- Mac Pro

- Magic Mouse

- Time Capsule

- Magic Track Pad

- Airport Express

- Airport Extreme

RETAIL SERVICES

- iTunes

- App Store

- iBooks

- iMusic

- Apple Retail Stores

OPERATING SYSTEMS

- iOS

- OS X

SOFTWARE

- Aperture (photograph manipulation software)

- Apple Remote (desktop management software)

- FaceTime for Mac (video calling interface)

- Final Cut Pro X (digital video editing software)

- iMovie

- iPhoto

- iWork

- iWeb

- iDVD

- Keynote

- Pages

- Numbers

- GarageBand

- Logic Studio

- Safari

CLOUD SERVICES

- iCloud

Turn page for more

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN

In only one decade, Apple has redefined the music industry (through the iPod and iTunes), as well as how we consume all media (through the iPhone and the iPad).

- Revenue: Apple’s 2012 revenue of $156 billion (compared to Microsoft’s $74 billion) is more than the GDP of Hungary. Apple could buy RIM, Nokia, Twitter, Adobe, and T-Mobile tomorrow, and still have extra cash.1

- Salary Disparity: In 2012, Apple CEO Tim Cook earned $4.2 million. Apple Store employees earn about $25,000 a year.2 The 230,000 employees who work for China’s massive factory plant in Foxconn City, where the iPhone is assembled, earn about $1.50 an hour.3

- Music Hub: iTunes has been the No. 1 music retailer in the United States since 2008. By 2013, iTunes had sold more than 25 billion songs. Apple has sold 300 million iPods since 2001.4

- “Post-PC” Revolution: In 2012, Apple sold 218 million “post-PC” devices.5 Apple controls 39 percent of the smartphone market in the United States, 80 percent of the MP3 player market, and 70 percent of the tablet market.6

- Apps: By May 2013, Apple had sold more than 50 billion apps.7

- Retail Behemoth: Apple operates 390 retail stores. In 2012, these stores took in more money per square foot than any other United States retailer.8