Production, Distribution, and Exhibition Today

In the 1970s, attendance by young moviegoers at new suburban multiplex theaters made megahits of The Godfather (1972), The Exorcist (1973), Jaws (1975), Rocky (1976), and Star Wars (1977). During this period, Jaws and Star Wars became the first movies to gross more than $100 million at the U.S. box office in a single year. In trying to copy the success of these blockbuster hits, the major studios set in place economic strategies for future decades. (See “Media Literacy and the Critical Process: The Blockbuster Mentality”.)

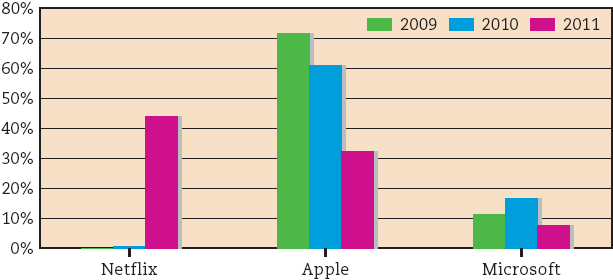

Source: Motion Picture Associa-tion of America, “Theatrical Market Statistics, 2012, U.S./Canada,” http://www.mpaa.org.

Making Money on Movies Today

“Google, Inc. says searches for a film’s title two weeks ahead of opening can predict box office with 92 percent accuracy.”

ASSOCIATED PRESS, 2013

With 80 to 90 percent of newly released movies failing to make money at the domestic box office, studios need a couple of major hits each year to offset losses on other films. (See Table 7.1 for a list of the highest-grossing films of all time.) The potential losses are great: Over the past decade, a major studio film, on average, cost about $66 million to produce and about $37 million for domestic marketing, advertising, and print costs.15

With climbing film costs, creating revenue from a movie is a formidable task. Studios make money on movies from six major sources: First, the studios get a portion of the theater box-office revenue—about 40 percent of the box-office take (the theaters get the rest). Overall, box-office receipts provide studios with approximately 20 percent of a movie’s domestic revenue. More recently, studios have found that they often can reel in bigger box-office receipts for 3-D films and their higher ticket prices. For example, admission to the 2-D version of a film costs $14 at a New York City multiplex, while the 3-D version costs $18 at the same theater. In 2012, nearly half of all moviegoers—and nearly one-third of the general population—attended a 3-D film. As Hollywood makes more 3-D films (the latest form of product differentiation), the challenge for major studios has been to increase the number of digital 3-D screens across the country. By 2013, about 30 percent of theater screens were digital 3-D.

Second, about four months after the theatrical release come the DVD sales and rentals, and digital downloads and streaming. This “window” accounts for about 30 percent of all domestic-film income for major studios, and has been declining since 2004 as DVD sales falter. Discount rental kiosk companies like Redbox must wait twenty-eight days after DVDs go on sale before they can rent them, and Netflix has entered into a similar agreement with movie studios in exchange for more video streaming content—a concession to Hollywood’s preference for the greater profits in selling DVDs rather than renting them. A small percentage of this market includes “direct-to-DVD” films, which don’t have a theatrical release.

Third are the next “windows” of release for a film: pay-per-view, premium cable (such as HBO), then network and basic cable, and, finally, the syndicated TV market. The price these cable and television outlets pay to the studios is negotiated on a film-by-film basis, although digital services like Netflix and premium channels also negotiate agreements with studios to gain access to a library of films. The cable window has traditionally begun with the DVD release window, but DirecTV threatened that system in 2011 by offering Hollywood films on demand just thirty to sixty days after their theatrical release. This shortening of the box-office window upset movie theater owners and many film directors.

TABLE 7.1 The top 10 all-time Box-office Champions*

| Rank | Title/Date | Domestic Gross** ($ millions) |

| 1 | Avatar (2009) | $760.5 |

| 2 | Titanic (1997, 2012 3-D) | 658.6 |

| 3 | The Avengers (2012) | 623.4 |

| 4 | The Dark Knight (2008) | 533 |

| 5 | Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace (1999, 2012 3-D) | 474.5 |

| 6 | Star Wars (1977, 1997) | 461 |

| 7 | The Dark Knight Rises (2012) | 447.8 |

| 8 | Shrek 2 (2004) | 437.7 |

| 9 | E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982, 2002) | 435 |

| 10 | Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (2006) | 423.3 |

Source: “All-Time Domestic Blockbusters,” November 12, 2013, http://www.boxofficeguru.com/blockbusters.htm.

*Most rankings of the Top 10 most popular films are based on American box-office receipts. If these were adjusted for inflation, Gone with the Wind (1939) would become No. 2 in U.S. theater revenue.

**Gross is shown in absolute dollars based on box-office sales in the United States and Canada.

Fourth, studios earn revenue from distributing films in foreign markets. In fact, at $23.9 billion in 2012, international box-office gross revenues are more than double the U.S. and Canadian box-office receipts, and they continue to climb annually, even as other countries produce more of their own films.

Fifth, studios make money by distributing the work of independent producers and filmmakers, who hire the studios to gain wider circulation. Independents pay the studios between 30 and 50 percent of the box-office and video rental money they make from movies.

Sixth, revenue is earned from merchandise licensing and product placements in movies. In the early days of television and film, characters generally used generic products, or product labels weren’t highlighted in shots. For example, Bette Davis’s and Humphrey Bogart’s cigarette packs were rarely seen in their movies. But with soaring film production costs, product placements are adding extra revenues while lending an element of authenticity to the staging. Famous product placements in movies include Reese’s Pieces in E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Pepsi-Cola in Back to the Future II (1989), and Warby Parker eyeglasses in Man of Steel (2013).

Theater Chains Consolidate Exhibition

Film exhibition is now controlled by a handful of theater chains; the leading seven companies operate more than 50 percent of U.S. screens. The major chains—Regal Cinemas, AMC Entertainment, Cinemark USA, Carmike Cinemas, Cineplex Entertainment, Rave Motion Pictures, and Marcus Theatres—own thousands of screens each in suburban malls and at highway crossroads, and most have expanded into international markets as well. Because distributors require access to movie screens, they do business with chains that control the most screens. In a multiplex, an exhibitor can project a potential hit on two or three screens at the same time; films that do not debut well are relegated to the smallest theaters or bumped quickly for a new release.

The strategy of the leading theater chains during the 1990s was to build more megaplexes (facilities with fourteen or more screens), but with upscale concession services and luxurious screening rooms with stadium-style seating and digital sound to make moviegoing a special event. Even with record box-office revenues, the major movie theater chains entered the 2000s in miserable financial shape. After several years of fast-paced building and renovations, the major chains had built an excess of screens and had accrued enormous debt. But to further combat the home theater market, movie theater chains added IMAX screens and digital projectors so that they could exhibit specially mastered and (with a nod to the 1950s) 3-D blockbusters.16 By 2011, the movie exhibition business had grown to a record number (39,580) of indoor screens.

Still, theater chains sought to be less reliant on Hollywood’s product, and with new digital projectors they began to screen nonmovie events, including live sporting events, rock concerts, and classic TV show marathons. One of the most successful theater events is the live HD simulcast of the New York Metropolitan Opera’s performances, which began in 2007 and during its 2013–14 season screened ten operas in more than 1,900 locations in sixty-four countries worldwide.