Newspaper Operations

“We received no extra space for 9/11. We received no extra space for the Iraq war. We’re all doing this within our budget. It is a zero-sum game. If something is more important, something else may be a little less important, a little less deserving of space.”

JOHN GEDDES, MANAGING EDITOR, NEW YORK TIMES, 2006

Today, a weekly paper might employ only two or three people, while a major metro daily might have a staff of more than one thousand, including workers in the newsroom and online operations, and in departments for circulation (distributing the newspaper), advertising (selling ad space), and mechanical operations (assembling and printing the paper). In either situation, however, most newspapers distinguish business operations from editorial or news functions. Journalists’ and readers’ praise or criticism usually rests on the quality of a paper’s news and editorial components, but business and advertising concerns today dictate whether papers will survive.

Most major daily papers would like to devote one-half to two-thirds of their pages to advertisements. Newspapers carry everything from full-page spreads for department stores to shrinking classified ads, which consumers can purchase for a few dollars to advertise used cars or old furniture (although many Web sites now do this for free). In most cases, ads are positioned in the paper first. The newshole—space not taken up by ads—accounts for the remaining 35 to 50 percent of the content of daily newspapers, including front-page news. The newshole and physical size of many newspapers had shrunk substantially by 2010.

News and Editorial Responsibilities

The chain of command at most larger papers starts with the publisher and owner at the top and then moves, on the news and editorial side, to the editor in chief and managing editor, who are in charge of the daily news-gathering and writing processes. Under the main editors, assistant editors have traditionally run different news divisions, including features, sports, photos, local news, state news, and wire service reports that contain major national and international news. Increasingly, many editorial positions are being eliminated or condensed to a single editor’s job.

Reporters work for editors. General assignment reporters handle all sorts of stories that might emerge—or “break”—in a given day. Specialty reporters are assigned to particular beats (police, courts, schools, local and national government) or topics (education, religion, health, environment, technology). On large dailies, bureau reporters also file reports from other major cities. Large daily papers feature columnists and critics who cover various aspects of culture, such as politics, books, television, movies, and food. While papers used to employ a separate staff for their online operations, the current trend is to have traditional reporters file both print and online versions of their stories—accompanied by images or video they are responsible for gathering.

Recent consolidation and cutbacks have led to layoffs and the closing of bureaus outside a paper’s city limits. For example, in 1985 more than six hundred newspapers had reporters stationed in Washington, D.C.; in 2013 that number was under 250. The Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, and the Baltimore Sun—all owned by the Tribune Company—closed their independent bureaus in 2009, choosing instead to share reports.36 The downside of this money-saving measure is that far fewer versions of stories are being produced and readers must rely on a single version of a news report. According to the American Society of Newspaper Editors (ASNE), the workforce in daily U.S. newsrooms declined by 11,000 jobs in 2008 and 2009.37 A small turnaround occurred in 2010 with 100 new jobs created overall, driven by the increase of 220 jobs in “freestanding digital news organizations.”38 But ASNE reports that the total number of newsroom jobs fell by 3,600 in 2011 and 2012, from 41,600 to 38,000.39

Wire Services and Feature Syndication

Major daily papers might have one hundred or so local reporters and writers, but they still cannot cover the world or produce enough material to fill up the newshole each day. Newspapers also rely on wire services and syndicated feature services to supplement local coverage. A few major dailies, such as the New York Times, run their own wire services, selling their stories to other papers to reprint. Other agencies, such as the Associated Press (AP) and United Press International (UPI), have hundreds of staffers stationed throughout major U.S. cities and world capitals. They submit stories and photos each day for distribution to newspapers across the country. Some U.S. papers also subscribe to foreign wire services, such as Agence France-Presse in Paris or Reuters in London.

Daily papers generally pay monthly fees for access to all wire stories. Although they use only a fraction of what is available over the wires, editors routinely monitor wire services each day for important stories and ideas for local angles. Wire services have greatly expanded the reach and scope of news, as local editors depend on wire firms when they select statewide, national, or international reports for reprinting.

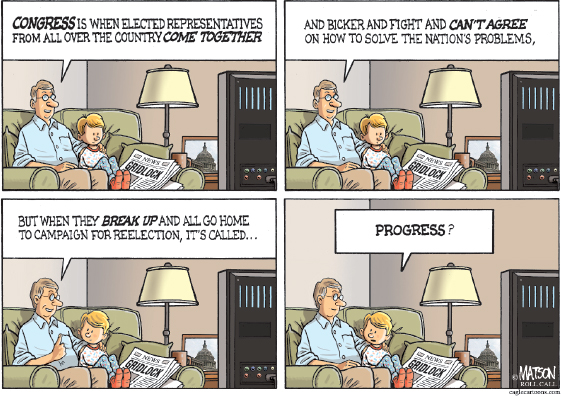

In addition, feature syndicates, such as United Features and Tribune Media Services, are commercial outlets that contract with newspapers to provide work from the nation’s best political writers, editorial cartoonists, comic-strip artists, and self-help columnists. These companies serve as brokers, distributing horoscopes and crossword puzzles as well as the political columns and comic strips that appeal to a wide audience. When a paper bids on and acquires the rights to a cartoonist or columnist, it signs exclusivity agreements with a syndicate to ensure that it is the only paper in the region to carry, say, Clarence Page, Maureen Dowd, Leonard Pitts, Connie Schultz, George Will, or cartoonist Mike Peters. Feature syndicates, like wire services, wield great influence in determining which writers and cartoonists gain national prominence.