The Print Era

Printed Page 6

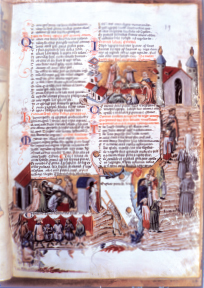

What we recognize as modern printing—the wide dissemination of many copies of particular manuscripts—became practical in Europe around the middle of the fifteenth century. At this time, Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of movable metallic type and the printing press in Germany ushered in the modern print era. Printing presses—and the publications they enabled—spread rapidly across Europe in the late 1400s and early 1500s. But early on, many books were large, elaborate, and expensive. It took months to illustrate and publish these volumes, and they were usually purchased by wealthy aristocrats, royal families, church leaders, prominent merchants, and powerful politicians.

In the following centuries, printers reduced the size and cost of books, making them available and affordable to more people. Books could then be mass-produced—and they became the first mass-marketed products in history. This development spurred significant changes: specifically, an increasing resistance to authority figures, the rise of new socioeconomic classes, the spread of literacy, and a focus on individualism.

Resistance to Authority

Since mass-produced printed materials could spread information and ideas faster and farther than ever before, writers could use print to disseminate views that challenged traditional civic doctrine and religious authority. This paved the way for major social and cultural changes, such as the Protestant Reformation and the rise of modern nationalism. People who read contradictory views began resisting traditional clerical authority. With easier access to information about events in nearby places, people also started seeing themselves not merely as members of families, isolated communities, or tribes, but as participants in larger social units—nation-states—whose interests were broader than local or regional concerns.

New Socioeconomic Classes

Eventually, mass production of books inspired mass production of other goods. This development led to the Industrial Revolution and modern capitalism in the mid-nineteenth century. The nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw the rise of a consumer culture, which encouraged mass consumption to match the output of mass production. The revolution in industry also sparked the emergence of a middle class. This class was comprised of people who were neither poor laborers nor wealthy political or religious leaders, but who made modest livings as merchants, artisans, and service professionals such as lawyers and doctors.

In addition to a middle class, the Industrial Revolution also gave rise to an elite class of business owners and managers who acquired the kind of influence once held only by the nobility or the clergy. These groups soon discovered that they could use print media to distribute information and maintain social order.

Spreading Literacy

Although print media secured authority figures’ power, the mass publication of pamphlets, magazines, and books also began democratizing knowledge—making it available to more and more people. Literacy rates rose among the working and middle classes, and some rulers fought back. In England, for instance, the monarchy controlled printing press licenses until the early nineteenth century to constrain literacy and therefore sustain the Crown’s power over the populace. Even today, governments in many countries worldwide control presses, access to paper, and advertising and distribution channels—for the same reason. In most industrialized countries, such efforts at control met with only limited success. After all, building an industrialized economy required a more educated workforce, and printed literature and textbooks supported that education.

Focus on Individualism

The print revolution also nourished the idea of individualism. People came to rely less on their local community and their commercial, religious, and political leaders for guidance on how to live their lives. Instead, they read various ideas and arguments, and came up with their own answers to life’s great questions. By the mid-nineteenth century, individualism had spread into the realm of commerce. There, it took the form of increased resistance to government interference in the affairs of self-reliant entrepreneurs. Over the next century, individualism became a fundamental value in American society.