Newspapers: The Rise and Decline of Modern Journalism

Printed Page 60

63

The Early History of American Newspapers

69

The Evolution of Newspapers: Competing Models of Modern Print Journalism

76

Categorizing News and U.S. Newspapers

79

The Economics of Newspapers

83

Challenges Facing Newspapers

89

Newspapers in a Democratic Society

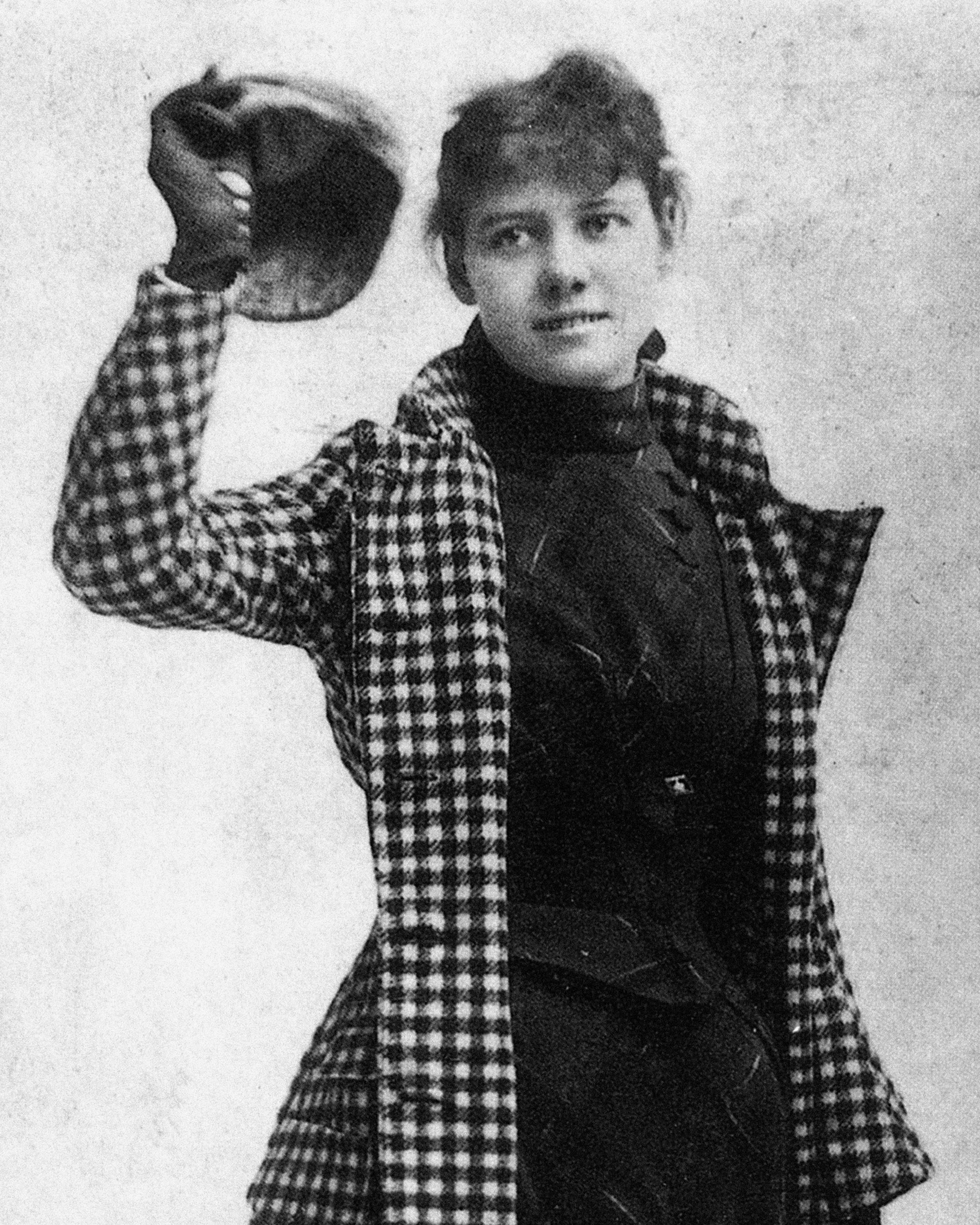

In 1887, a young reporter left her job at the Pittsburgh Dispatch to seek her fortune in New York City. Only twenty-three years old, Elizabeth “Pink” Cochrane had grown tired of writing for the society pages and answering letters to the editor. She wanted to be on the front page. But at that time, it was considered “unladylike” for women journalists to use their real names, so the Dispatch editors, borrowing from a Stephen Foster song, had dubbed her “Nellie Bly.”

After four months of persistent job hunting and freelance writing, Nellie Bly earned a tryout at Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, the nation’s biggest paper. Her assignment: to investigate conditions at the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island. Her method: to get herself committed to the asylum. After practicing the look of a disheveled lunatic in front of mirrors, she wandered city streets unwashed and seemingly dazed, and acted crazy around her fellow boarders in a New York rooming house.1 Her tactics worked: Doctors declared her mentally deranged and had her committed.

Ten days later, an attorney from the World went in to get her out. Her two-part story appeared in October 1887 and caused a sensation. Nellie Bly’s dramatic first-person accounts documented harsh cold baths; attendants who abused and taunted patients; and newly arrived immigrant women, completely sane, who were dragged to the asylum simply because no one could understand them. Bly became famous. Pulitzer gave her a permanent job, and New York City committed $1 million toward improving its asylums. Through her courageous work, Bly had pioneered what was then called detective or stunt journalism. Her work inspired the twentieth-century practice of investigative journalism.

ALONG WITH THEIR INVESTIGATIVE ROLE, newspapers have played many roles in Americans’ lives. As chroniclers of daily life, newspapers both inform and entertain—providing articles on everything from science, technology, and medicine to books, music, and movies and stimulating public debate through their news analyses, opinion pages, and letters to the editor. Moreover, newspapers form the bedrock for other mass media. TV, radio, and online outlets like Google all rely extensively on newspaper journalists’ work for their content. While print journalism may not be as eye-catching as TV news footage or as up-to-the-minute as online news reports, it offers a much more in-depth, long-term examination of events than these other media.

Still, newspapers struggle mightily to stay in business in today’s digital age. Most are losing money as ad revenues have been dropping steadily for some time; to make matters worse, ad revenues fell 30 percent in 2009 alone in the wake of the global financial meltdown, and the erosion continued with a drop of 7 percent in the first quarter of 2011.2 Some newspapers, such as the Ann Arbor News and Detroit Free Press, began publishing a print version only two or three days per week; others like the Seattle Post-Intelligencer now publish only online; and many—like the Chicago Tribune and Philadelphia Inquirer—have declared bankruptcy. U.S. newspapers have lost readers as well as their near monopoly on classified advertising, much of which has shifted to popular Web sites like craigslist.com. Industry observers now regularly ask, “Can this mass medium survive much longer?”

In this chapter, we examine newspapers’ unique history, their role in our lives, and the challenges now facing them by:

- exploring newspapers’ early history, including the rise of the political-commercial press, penny papers, and yellow journalism

- assessing the modern era of print journalism, including the tensions between objective and interpretive journalism

- considering the diverse array of newspaper types in existence today, such as local and ethnic papers as well as the underground press

- examining the economics behind print journalism

- taking stock of the challenges facing newspapers today, such as industry consolidation and the digitization of content

- considering how newspapers’ current struggles may affect the strength of our democracy