General-Interest Magazines Hit Their Stride

Printed Page 102

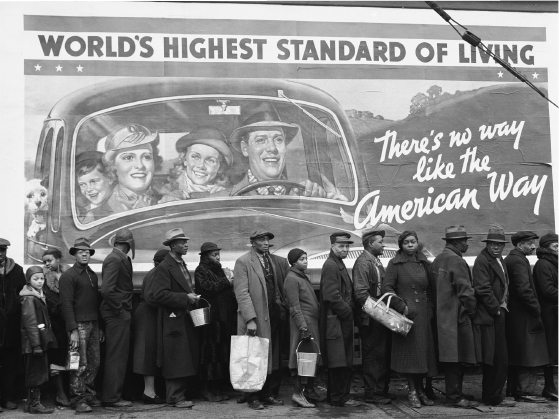

The heyday of the muckraking era lasted into the mid-1910s, when America was drawn into World War I. During the next few decades and even through the 1950s, general-interest magazines gained further prominence. These publications offered occasional investigative articles but also covered a wide variety of topics aimed at a broad national audience—such as recent developments in government, medicine, or society. A key aspect of these magazines was photojournalism—the use of photographs to augment editorial content (see “Media Literacy Case Study: The Evolution of Photojournalism”). High-quality photos gave general-interest magazines a visual advantage over radio, which was the most popular medium of the day. In 1920, about fifty-five magazines fit the general-interest category; by 1946, more than a hundred such magazines competed with radio networks for the national audience. This genre of magazine was dominated by four giants: the Saturday Evening Post, Reader’s Digest, Time, and Life.

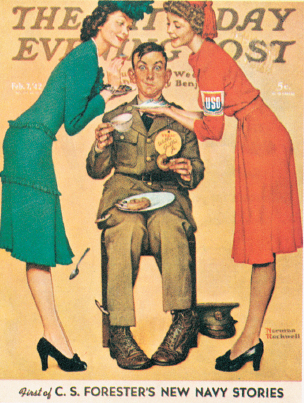

Saturday Evening Post

Although the Post had been around since 1821, Cyrus Curtis (who bought it in 1897) transformed it into the first widely popular general-interest magazine by printing popular fiction and romanticizing American virtues through words and pictures. During the 1920s, Curtis also featured articles celebrating the business boom of the decade. This reversed the journalistic direction of the muckraking era, in which magazines focused on exposing corruption in business. By the 1920s, the Post had reached two million in circulation, the first magazine to hit that mark.

Reader’s Digest

Reader’s Digest championed one of the earliest functions of magazines: printing condensed versions of selected articles from other magazines. With its inexpensive production costs, low price, and popular pocket-size format, the magazine saw its circulation climb to more than one million even during the depths of the Great Depression. By 1946, it was the nation’s most popular magazine, with a circulation of more than nine million. By the mid-1980s, it was the most popular magazine in the world.

Time

During the general-interest era, national newsmagazines such as Time also scored major commercial successes. Begun in 1923, Time developed a magazine brand of interpretive journalism, assigning reporter-researcher teams to cover newsworthy events while a rewrite editor would shape the teams’ findings into articles presenting a point of view on the events covered. Newsmagazines took over photojournalism’s role in news reporting, visually documenting both national and international events. Today, Time’s circulation stands at about 2.6 million.

Life

More than any other magazines of its day, Life, an oversized pictorial weekly, struck back at radio’s popularity by advancing photojournalism. Launched in 1936, Life satisfied the public’s fascination with images (invigorated by the movie industry) by featuring extensive photo spreads with its researched articles, lavish advertisements, and even fashion photography. By the end of the 1930s, Life had a pass-along readership—the total number of people who come into contact with a single copy of a magazine—of more than seventeen million. This rivaled the ratings of even the most popular national radio programs.