MEDIA LITERACY: The Evolution of Photojournalism

Printed Page 104

MEDIA LITERACY

Case Study

The Evolution of Photojournalism

By Christopher R. Harris

What we now recognize as photojournalism started with the assignment of photographer Roger Fenton, of the Sunday Times of London, to document the Crimean War in 1856. Since then—from the earliest woodcut technology to halftone reproduction to the flexible-film camera—photojournalism’s impact has been felt worldwide, capturing many historic moments and playing an important political and social role. For example, Jimmy Hare’s photoreportage on the sinking of the battleship Maine in 1898 near Havana, Cuba, fed into growing popular support for Cuban independence from Spain and eventual U.S. involvement in the Spanish-American War; the documentary photography of Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine at the turn of the twentieth century captured the harsh working and living conditions of the nation’s many child laborers. Reaction to these shockingly honest photographs resulted in public outcry and new laws against the exploitation of children. In addition, Timemagazine’s coverage of the Roaring Twenties to the Great Depression and Life’simages from World War II and the Korean War changed the way people viewed the world.

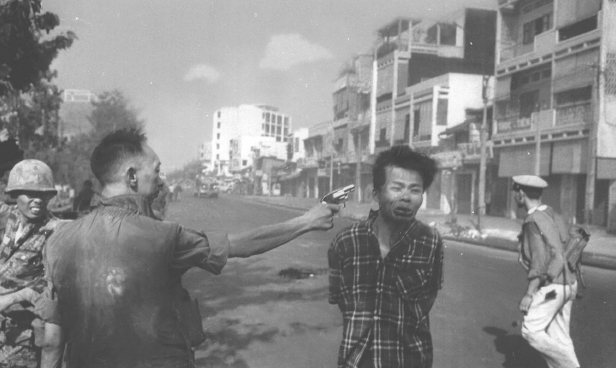

With the advent of television, photojournalism continued to take on a significant role, bringing to the public live coverage of the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963 and its aftermath as well as visual documentation of the turbulent 1960s, including aggressive photographic coverage of the Vietnam War and shocking images of the Civil Rights movement.

Into the 1970s and onward, new computer technologies emerged which have brought about new technological ethical concerns with photojournalism. These new concerns primarily deal with the ability of photographers and photo editors to change or digitally alter the documentary aspects of a news photograph. By the late 1980s, computers could transform images into digital form, easily manipulated by sophisticated software programs. In addition, any photographer can now transmit images around the world almost instantaneously by using digital transmission, and the Internet allows publication of virtually any image, without censorship. Because of the absence of physical film, there is a resulting loss of proof, or veracity, of the authenticity of images. Digital images can be easily altered, but such alteration can be very difficult to detect.

A recent example of image-tampering involved the Men’s Health cover photo of tennis star Andy Roddick. Roddick, who is muscular but not bulky, didn’t consent to the digital enhancement of his arms and later joked on his blog: “Little did I know I had 22-inch guns,” referring to the size of his arms in the photo. (A birthmark on his right arm had also been erased.) A Men’s Health spokesman said “I don’t see what the big issue is here.”1

Have photo editors gone too far? Photojournalists and news sources are now confronted with unprecedented concerns over truth-telling. In the past, trust in documentary photojournalism rested solely on the verifiability of images as they were used in the media. Just as we must evaluate the words we read, at the start of a new century we must also view with a more critical eye these images that mean so much to so many.

Source: Christopher R. Harris is a professor in the Department of Electronic Media Communication at Middle Tennessee State University.

APPLYING THE CRITICAL PROCESS

DESCRIPTION Select three different types of magazines (for example, national, political, alternative) that contain photojournalistic images. Look through these magazines, taking note of what you see.

ANALYSIS Document patterns in each one. What kinds of images are included? What kinds of topics are discussed? Do certain stories or articles have more images than others? Are the subjects generally recognizable, or do they introduce readers to new people or places? Do the images accompany an article, or are they stand-alone, with or without a caption?

INTERPRETATION What do these patterns mean? Talk about what you think the orientation is of each magazine based upon the images. How do the photos work to achieve this view? Do the images help the magazine in terms of verification or truth-telling? Or, are the images mainly to attract attention? Can images do both?

EVALUATION Do you find the motives of each magazine to be clear? Can you see any examples where an image may be framed or digitally altered to convey a specific point of view? What are the dangers in this? Explain.

ENGAGEMENT If you find evidence that a photo has been altered, or has framed the subject in a manner that makes it less accurate, e-mail the magazine’s editor and explain why you think this is a problem.