Innovators in Wireless: Marconi, Fessenden, and De Forest

Printed Page 164

As the nineteenth century unfolded, inventors building on the earlier technologies continued improving wireless communication. New developments took wireless from narrowcasting (person-to-person or point-to-point transmission of messages) to broadcasting (transmission from one point to multiple listeners; also known as one-to-many communication).

Marconi: The Father of Wireless Telegraphy

In 1894, a twenty-year-old, self-educated Italian engineer named Guglielmo Marconi read Hertz’s work. He swiftly realized that developing a way to send high-speed messages over great distances would transform communication, commercial shipping, and the military. The young engineer set out to make wireless technology practical. After successfully figuring out how to build a wireless communication device that could send Morse code from a transmitter to a receiver, Marconi traveled to England in 1896. There, he received a patent on wireless telegraphy, a form of voiceless point-to-point communication.

In London the following year, the Italian inventor formed the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, later known as British Marconi. He began installing wireless technology on British naval and private commercial ships. This left other innovators to explore the wireless transmission of voice and music, later known as wireless telephony and eventually radio. In 1899, Marconi opened a branch in the United States nicknamed American Marconi. That same year, he sent the first wireless Morse code signal across the English Channel to France. In 1901, he relayed the first wireless signal from Cornwall, England, across the Atlantic Ocean to St. John’s, Newfoundland. History often cites Marconi as the “father of radio,” but a Russian scientist, Alexander Popov, accomplished similar feats in St. Petersburg at the same time, and Nikola Tesla, a Serbian Croatian inventor who immigrated to the United States, invented a wireless electrical device in 1892.

Fessenden: The First Voice Broadcast

Marconi had taken major steps in London and the United States. But it was Canadian engineer Reginald Fessenden who transformed wireless telegraphy into one-to-many communication. Fessenden is credited with providing the first voice broadcast. Formerly a chief chemist for Thomas Edison, he went to work for the U.S. Navy and eventually for General Electric (GE), where he focused on improving the frequency of wireless signals. Both the navy and GE were interested in the potential for voice transmission. On Christmas Eve in 1906, after GE built Fessenden a powerful transmitter, he gave his first public demonstration, sending his performance of “O Holy Night” on the violin and a reading of a Bible passage through the airwaves from his station at Brant Rock, Massachusetts, to an unknown number of shipboard operators off the Atlantic Coast.

De Forest: Birthing Modern Electronics

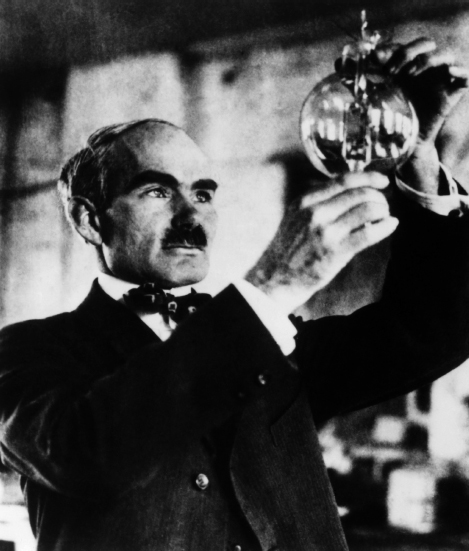

American inventor Lee De Forest improved the usefulness of broadcasting by greatly increasing listeners’ ability to hear dots and dashes, and later speech and music, on a receiver. In 1906, he developed the Audion vacuum tube, which detected and amplified radio signals. The device was essential to the development of voice transmission, long-distance radio, and (eventually) television. Although De Forest had the patent for the Audion, he was accused in court and by fellow engineers of stealing others’ ideas, even when the court ruled in his favor.2 Many historians consider the Audion—which powered radios until the arrival of transistors and solid-state circuits in the 1950s—the origin of modern electronics.

In 1907, De Forest demonstrated his invention’s power and practical value by broadcasting a performance by Metropolitan opera tenor Enrico Caruso to his friends in New York. The next year, he and his wife, Nora, played records into a microphone from atop the Eiffel Tower in Paris. The signals were picked up by receivers up to five hundred miles away.