The First Amendment beyond the Printed Page: Film and Broadcasting

Back when the Bill of Rights was ratified, our nation’s founders could not have predicted the advent of visual media. Film, which came into existence in the late 1890s, presented new challenges for those seeking to determine whether expression in film should be protected. The First Amendment said nothing explicit about film, so lawmakers, courts, society, and industry began an ongoing struggle over exactly how to apply it. As new communication technologies emerged, so did concerns over the impact of films and broadcast sounds and images on the values and morals of the public—especially children. It’s useful to understand how these ongoing battles over the limits of free speech have played out over the last century, as the model of self-regulation and self-censorship developed in the movie industry is often invoked in discussions of the regulation of video games, the Internet, and similar technologies (see also discussions about regulation in technology-specific chapters).

Citizens and Lawmakers Control the Movies

During the early part of the twentieth century, civic leaders in individual towns and cities formed local review boards, which screened movies to determine their moral suitability for the community. By 1920, more than ninety cities in the United States had such boards, which were composed of vice squad officers, politicians, or other citizens. By 1923, twenty-two states had such boards.

451

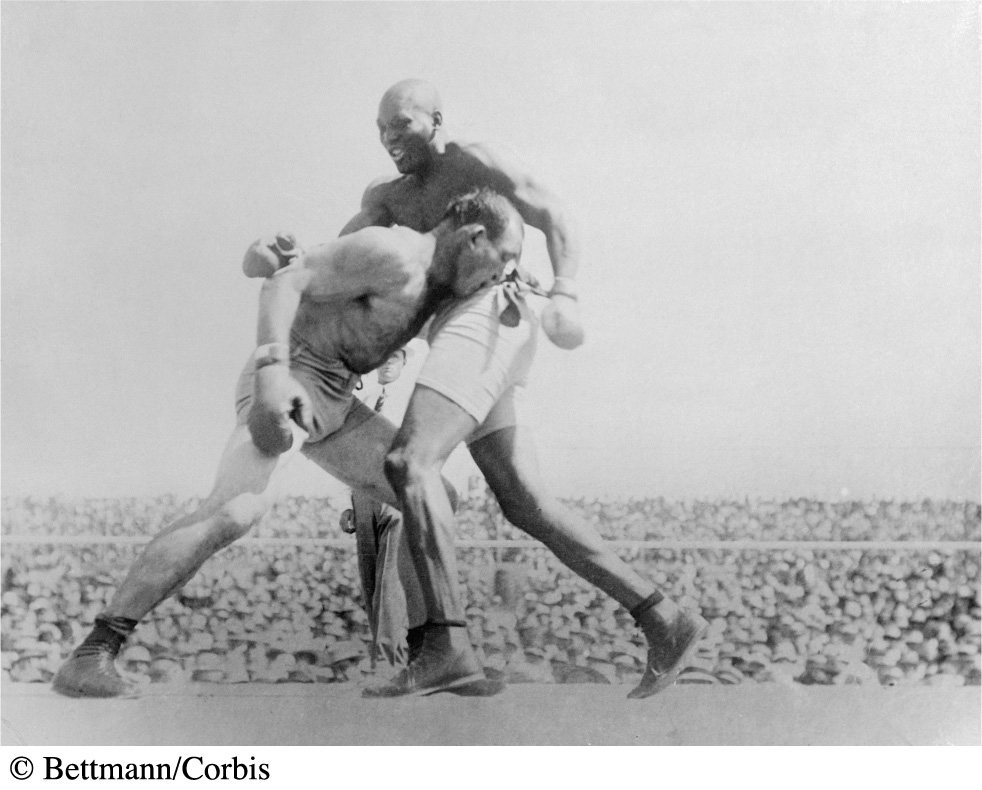

Meanwhile, lawmakers seeking to please their constituencies introduced legislation to control films. For example, after African American heavyweight champion Jack Johnson defeated white champion Jim Jeffries in 1910, the federal government outlawed transportation of boxing movies across state lines. The move reflected racist attitudes (a fear of images of a black man defeating a white man) more than distaste for violent imagery, as legislators pandered to white constituents who saw Johnson as a threat.

The idea of film as free speech took a big hit in 1915, when the Supreme Court decided in the Mutual v. Ohio case that films were “a business pure and simple” and thus not protected by the First Amendment. The Court further described the film industry as a circus, a “spectacle” for entertainment with “a special capacity for evil.”11

The Movie Industry Regulates Itself

In the early 1920s, a series of scandals—including the rape and murder of an aspiring actress at a party thrown by silent-film comedian Fatty Arbuckle—rocked Hollywood and pressured the movie industry to regulate itself before public review boards or the government could force regulations on them (or before audiences were driven away from movie theaters by the scandals). So over the next few decades, the industry set up its own way of policing not only the content of films but also the personal lives of actors, directors, and others involved in the moviemaking process.

The Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America

In the 1920s, industry leaders hired Will Hays, a former Republican National Committee chair, as president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA). Under Hays, promising actors or movie extras who had even minor police records were blacklisted, meaning they were put on a list of people who would subsequently not be hired by any of the movie studios. Hays also developed a public relations division for the MPPDA, which promptly squelched a national movement to create a federal law censoring movies.

452

The Motion Picture Production Code

In the early 1930s, the Hays Office established the Motion Picture Production Code. The code stipulated that “no picture shall be produced which will lower the moral standards of those who see it. Hence the sympathy of the audience shall never be thrown to the side of crime, wrong-doing, evil or sin.” The code also dictated which phrases, images, and topics producers and directors had to avoid. For example, “excessive and lustful kissing” and “suggestive postures” were not allowed. The code also prohibited negative portrayals of religion or religious figures. Anyone who broke these rules was blacklisted.

Almost every executive in the industry adopted the code, viewing it as better than regulation coming from the government, and it influenced most commercial movies for the next twenty years. The level of self-censorship and control Hays and his organization achieved under this “voluntary” self-censorship and blacklisting was arguably greater than the government could have achieved on its own. Not only did this stifle creativity and critique, but it spread with anticommunist hysteria in the mid-twentieth century, when individuals could get blacklisted for the merest suspicion of communist sympathies.

This ideologically based blacklisting, inherently a violation of a citizens First Amendment rights, hit its peak in the 1950s, just as the grip of Hays’s motion picture code was about to crumble. In 1952, the Supreme Court decided in Burstyn v. Wilson that New York could not ban the Italian film The Miracle under state regulations barring “sacrilegious” films. The Court had decided that movies were an important vehicle for public opinion, putting American movies on the same footing as books and newspapers in terms of protection under the First Amendment.

The Rating System and Forced Self-Censorship

In the wake of the 1952 Miracle case and the demise of the production code, renewed discontent over sexual language and imagery in movies pushed the MPPDA (renamed the Motion Picture Association of America, or MPAA) in the late 1960s to establish a movie-rating system to help concerned viewers avoid offensive material. Eventually, G, PG, R, and X ratings (X isn’t used by the MPAA but as a promotional tool by adult filmmakers) emerged as guideposts for films’ suitability for various age groups. In 1984, the MPAA added the PG-13 rating to distinguish slightly higher levels of violence or adult themes in movies that might otherwise qualify as PG, and later the NC-17 rating (no children under 17) for films with strong content that nevertheless aren’t pornographic (see Table 13.1).

| Rating | Description |

|---|---|

| G | General Audiences: All ages admitted; contains nothing that would offend parents when viewed by their children. |

| PG | Parental Guidance Suggested: Parents urged to give “parental guidance,” as it may contain some material they may not find suitable for their young children. |

| PG-13 | Parents Strongly Cautioned: Parents should be cautious because some content may be inappropriate for children under the age of 13. |

| R | Restricted: The film contains some adult material. Parents/guardians are urged to learn more about it before taking children under the age of 17 with them. |

| NC-17 | No one 17 and under admitted: Adult content. Children are not admitted. |

Data from: Motion Picture Association of America, “Understanding the Film Ratings,” accessed April 22, 2015, www.mpaa.org/film-ratings

453

Ratings have an important relationship to the ability of a film to make money. An R can sometimes have a negative effect, but an NC-17 in most cases is seen as a kiss of death, not least because several major theater chains refuse to screen films rated NC-17, and many outlets won’t run ads for them. Critics have attacked the system for being secretive (in theory, the identities of ratings board members is kept anonymous) and for applying standards arbitrarily and unequally. For example, violence is generally more acceptable than nudity or sexual content, and often similar sex scenes can earn films wildly different ratings, depending on the scene’s point of view. Critics say this forces directors and producers to re-edit films in ways that silence the voices of certain groups in order to avoid an NC-17 rating—and probable bankruptcy. This raises important free-speech questions not only for movies but also for the industries that look to the film industry as a model of self-regulation (and self-censorship).