U.S. Popular Music and the Rise of Rock

As sound recording became a mass medium, it fueled the growth of popular music, or pop music, which appeals to large segments of the general population or sizable groups distinguished by age, region, or ethnic background. Pop music today includes numerous genres—rock and roll, jazz, blues, country, Tejano, salsa, reggae, punk, hip-hop, and dance—many of which evolved from a common foundation. For example, rock splintered off from blues (which originated in the American South), and hip-hop grew out of R&B, dance music, and rock. This proliferation of music genres created a broad range of products that industry players could package and sell—targeted to increasingly narrow listener groups.

155

It would be a mistake to think of the label “pop music” as an insult, somehow referring to music that is frivolous, unimportant, or unartistic. To be sure, some music is indeed just meant to entertain (or to separate consumers from their dollars). But from the folk music protests of Woody Guthrie to the blurring of racial lines in the development of rock music to the antiwar anthem “What’s Going On” by Marvin Gaye, popular music has exerted a major influence on society, culture, and even politics.

The Rise of Pop Music

Though technological advancements made sound recording a mass medium and sparked the proliferation of pop music genres, this music had its earliest roots in something far less technical: sheet music. With mass production of sheet music in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, pop developed into a business fed by artists who set standards for the different genres—including jazz, rock, blues, and R&B.

Back in the late nineteenth century, a section of Broadway in Manhattan known as Tin Pan Alley began selling sheet music for piano and other instruments. (The name Tin Pan Alley referred to the way these quickly produced tunes supposedly sounded like cheap pans clanging together.) Songwriting along Tin Pan Alley helped transform pop music into big business. At the turn of the twentieth century, improvements in printing technology enabled song publishers to mass-produce sheet music for a growing middle class. Previously a novelty, popular music now became a major enterprise. With the emergence of the phonograph and recorded tunes, interest in and sales of sheet music soared. (These sales would eventually decline with the rise of radio in the 1920s, which turned audiences more into listeners of music than active participants playing instruments to sheet music in their living rooms.)

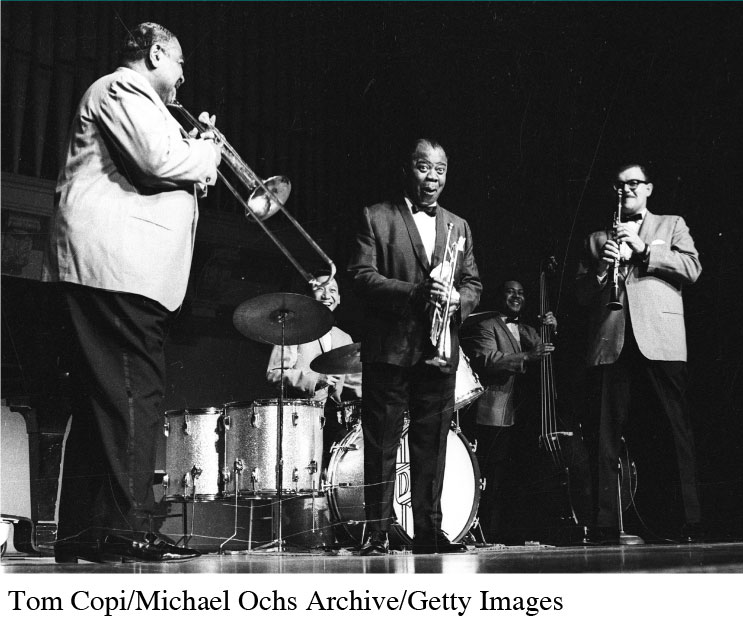

As sheet music gained popularity and phonograph sales rose, jazz developed in New Orleans. An improvisational and mostly instrumental musical form, jazz absorbed and integrated a diverse array of musical styles, including African rhythms, blues, and gospel. Groups led by Louis Armstrong, Tommy Dorsey, and others counted among the most renowned of the “swing” jazz bands, whose rhythmic sound dominated radio, recordings, and dance halls.

156

158

The first pop vocalists of the twentieth century came out of vaudeville—stage performances featuring dancing, singing, comedy, and magic shows. By the 1930s, Rudy Vallée and Bing Crosby had established themselves as the first “crooners” singing pop standards. Bing Crosby also popularized Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas,” which became one of the most covered songs in recording history. (A song recorded or performed by another artist is known as cover music.) Meanwhile, the bluesy harmonies of a New Orleans vocal trio, the Boswell Sisters, influenced the Andrews Sisters, whose boogie-woogie style sold more than sixty million records in the late 1930s and 1940s. Helped by radio, pop vocalists like Frank Sinatra in the 1940s were among the first singers to win the hearts of a large national teen audience. Indeed, Sinatra’s early performances incited the kinds of audience riots that would later characterize rock-and-roll concerts.

Rock and Roll Arrives

Pop music’s expanding appeal paved the way for rock and roll to emerge in the mid-1950s. Rock both reflected and shaped powerful societal forces (such as blacks’ migration from the South to the North and the growth of youth culture) that had begun transforming American life. Rock also stirred controversy. Like the word jazz, the phrase rock and roll was a blues slang expression meaning “sex”—which offended some people with more conservative tastes in music and made them worry about their children’s choice in music. Rock grew out of a blending of numerous musical styles. For instance, early rock combined the vocal and instrumental traditions of pop with the rhythm-and-blues sounds of Memphis and the country twang of Nashville. As rock and roll developed, that fusion of musical styles contributed to both racial progress and fears reflecting the social unease of the 1950s and 1960s.

Blues and R&B Set the Stage for Rock

The migration of southern blacks to northern cities in search of better jobs during the first half of the twentieth century helped disseminate different popular music styles to new places. In particular, blues music traveled north. Blues became the foundation of rock and roll and was influenced by African American spirituals, ballads, and work songs from the rural South.

159

Influential blues artists included Robert Johnson, Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Charley Patton. After the introduction of the electric guitar in the 1930s, blues-based urban black music began to be marketed under the name rhythm and blues (R&B). This new music appealed to young listeners fascinated by the explicit (and forbidden) sexual lyrics in songs like “Annie Had a Baby,” “Sexy Ways,” and “Wild Wild Young Men.” Although banned on some stations, R&B continued gaining popularity into the early 1950s. Still, black and white musical forms were segregated, and trade magazines in the 1950s tracked R&B record sales on “race” charts, separate from the white “pop” charts.

Rock Reflects and Reshapes Racial Politics

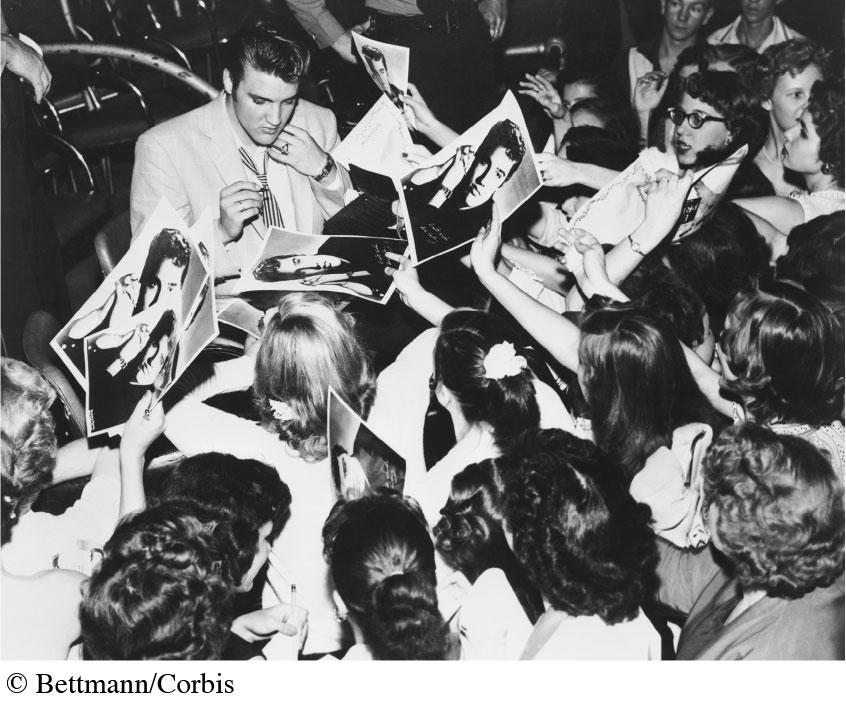

As artists began to produce music that borrowed from what mainstream society thought of as “black” and “white” musical traditions, American society as a whole was entering a tumultuous time of social and political change that would help fuel rock’s popularity. By the early 1950s, President Truman’s 1948 executive order integrating the armed forces was fully in practice, bringing young men from very different ethnic and economic backgrounds together. Then, in 1954, the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision declared unconstitutional the “separate but equal” laws that had segregated blacks and whites for decades. Mainstream America began to wrestle seriously with the legacy of slavery and the unequal treatment of its African American citizens. And so rock music reflected the complicated changes happening at the time while also helping to influence those changes. On the one hand, the fusion of musical traditions made rock music popular among young people across racial lines and could be understood as “desegregating” in its own right. On the other hand, sometimes the rock-and-roll business of the 1950s and 1960s (and beyond) perpetuated racial inequalities and denied artists of color the fruits of their artistic efforts. White producers would often give cowriting credit to white performers like Elvis Presley (who never wrote songs himself) for the tunes they covered. Many producers also bought the rights to potential hits from black songwriters, who seldom saw a penny in royalties or received songwriting credit.

By 1955, R&B hits regularly crossed over to the pop charts, but for a time the white cover versions were more popular and profitable. For example, Pat Boone’s cover of Fats Domino’s “Ain’t That a Shame” shot to No. 1 and stayed on the Top 40 pop chart for twenty weeks. Domino’s original made it only to No. 10. A turning point, however, came in 1962, when Ray Charles covered “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” a 1958 country song by the Grand Ole Opry’s Don Gibson. This marked the first time that a black artist covering a white artist’s song had notched a No. 1 pop hit.

160

Fear Fuels Censorship

Rock’s blurring of racial and other lines alarmed enough Americans that performers and producers alike worried that fans would begin defecting. They used various tactics to get people to accept the music. Cleveland deejay Alan Freed played original R&B recordings from the race charts and black versions of early rock on his program, while Philadelphia deejay Dick Clark took a different tactic—playing white artists’ cover versions of black music. Still, problems persisted that further eroded rock’s acceptance.

One particularly difficult battle rock faced was the perception among mainstream adults that the music caused juvenile delinquency. Such delinquency was statistically on the rise in the 1950s, owing to contributing factors such as parental neglect, the rising consumer culture, and the burgeoning youth population after World War II. But adults sought an easier culprit to blame. It was far simpler to point the finger at rock—especially artists who blatantly defied rules governing proper behavior. Authorities responded by censoring rock lyrics.

Rattled by this and other developments, the U.S. recording industry decided it needed a makeover. To protect the enormous profits the new music had been generating, record companies began practicing some censorship of their own. In the early 1960s, the industry introduced a new generation of clean-cut white singers, including Frankie Avalon, Connie Francis, Ricky Nelson, Lesley Gore, and Fabian. Rock’s explosive violations of racial, class, and other boundaries gave way to simpler generation gap problems, and the music—for a time—developed a milder reputation.

Rock Blurs Additional Boundaries

Although rock and roll was molded by powerful social, cultural, and political forces, it also shaped them in return. As we’ve seen, rock and roll began by blurring the boundary between black and white, but it broke down additional divisions as well—between high and low culture, masculinity and femininity, country and city, North and South, and the sacred and the secular.

High and Low Culture

Rock challenged the long-standing distinction between high and low culture initially through its lyrics and later through its performance styles. In 1956, Chuck Berry’s song “Roll Over Beethoven” merged rock and roll (which many people considered low culture) with high culture through lyrics that included references to classical music: “You know my temperature’s risin’ / And the jukebox’s blowin’ a fuse … Roll over Beethoven / And tell Tchaikovsky the news.” Rock artists also defied norms governing how musicians should behave: Berry’s “duck walk” sacross the stage, Elvis Presley’s tight pants and gyrating hips, and Bo Diddley’s use of the guitar as a phallic symbol shocked elite audiences—and inspired additional antics by subsequent artists.

161

Masculinity and Femininity

Rock and roll was also the first pop music genre to overtly challenge assumptions about sexual identity and orientation. Although early rock and roll largely attracted males as performers, the most fascinating feature of Elvis Presley, according to the Rolling Stones’ Mick Jagger, was his androgynous appearance.3 Little Richard (Penniman) took things even further, sporting a pompadour hairdo, decorative makeup, and feminized costumes during his performances.4

Country and City

Rock and roll also blended cultural borders between early-twentieth-century black urban rhythms and white country & western music. Early white rockers such as Buddy Holly and Carl Perkins combined country or hillbilly music, southern gospel, and Mississippi delta blues to create a sound called rockabilly. Conversely, rhythm and blues spilled into rock and roll. Many songs first popular on the R&B charts, such as “Rocket 88,” crossed over to the pop charts during the mid to late 1950s, though many of these songs were performed by more widely known white artists.

Rock lyrics in the 1950s may not have been especially provocative or overtly political by today’s standards, but soaring record sales and the crossover appeal of the music itself represented an enormous threat to long-standing racial and class divisions defined by geography. Distinctions at the time between traditionally rural white music and urban black music dissolved, as some black artists (such as Chuck Berry) strived to “sound white” to attract Caucasian fans, and some white artists (such as Elvis Presley) were encouraged by record producers to “sound black.”

North and South

Not only did rock and roll blur the line between urban and rural, but it also mixed northern and southern influences together. As many blacks migrated north during the early twentieth century, they brought their love of blues and R&B with them. Meanwhile, musicians and audiences in the North had claimed blues music as their own, forever extending its reach beyond its origins in the rural South. Some white artists from the South—most notably Carl Perkins, Elvis Presley, and Buddy Holly—further carried southern musical styles to northern listeners.

Sacred and Secular

Many mainstream adults in the 1950s complained that rock and roll’s sexual overtones and gender bending constituted an offense against God—even though numerous early rock figures (such as Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Little Richard) had strong religious upbringings. In the late 1950s, public outrage over rock proved so great that even Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis, both sons of southern preachers, became convinced that they were playing “the devil’s music.” Throughout the rock era and even today, boundaries between the sacred and the secular continue to blur through music. For example, some churches are using rock and roll to appeal to youth, and some Christian-themed rock groups are recording in seemingly incongruous musical styles, such as heavy metal.

162