The Early History of Radio

Radio did not emerge as a full-blown mass medium until the 1920s, though its development can be traced back to the introduction of the telegraph in the 1840s. As with most media, inventors tinkered in these earliest years with the technologies of the day to address practical needs. The telegraph and early experiments with wireless transmission set the stage for radio as a communication medium.

Inventors Paving the Way: Morse, Maxwell, and Hertz

186

The telegraph—the precursor of radio technology—was invented in the United States in the 1840s and was the first technology to enable messages to move faster than human travel. This meant that news and other messages could be transmitted from coast to coast within minutes, rather than the days required to physically carry information from place to place. American artist and inventor Samuel Morse initially developed this practical system of sending electrical impulses from a transmitter through a cable to a reception device. Telegraph operators used what became known as Morse code—a series of dots and dashes that stood for letters of the alphabet and interrupted the electrical current along a wire cable. By 1844, Morse had set up the first telegraph line, which linked Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland. By 1861, telegraph lines stretched from coast to coast. Just five years later, the first transatlantic cable, capable of transmitting about six words a minute, ran between Newfoundland and Ireland along the ocean floor.

Though revolutionary, the telegraph had significant limitations. For one thing, it couldn’t transmit the human voice. Moreover, because it depended on wires, it was useless for anyone seeking to communicate with ships at sea. The world needed a telegraph without wires. In the mid-1860s, Scottish physicist James Maxwell theorized the existence of radio waves, which could be harnessed to send signals from one place to another without wires. In the 1880s, German physicist Heinrich Hertz tested Maxwell’s theory by using electrical sparks that emitted electromagnetic waves, invisible electronic impulses similar to light. The experiment was the first recorded transmission and reception of radio waves, and would dramatically advance the development of wireless communication.

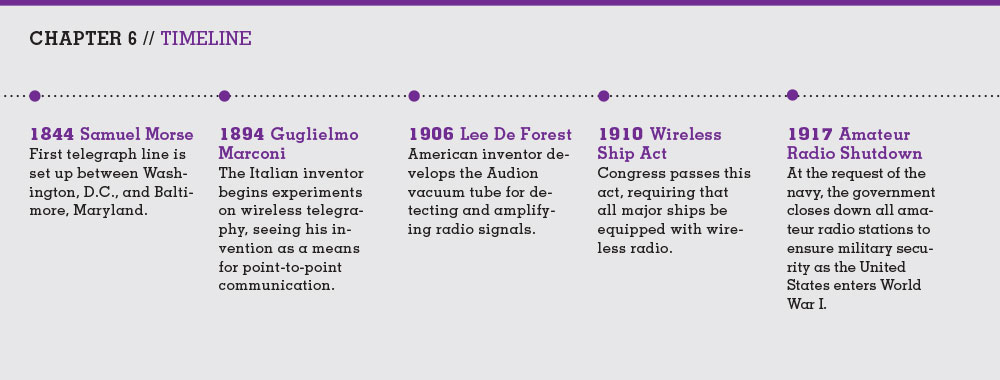

CHAPTER 6 // TIMELINE

1844 Samuel Morse

First telegraph line is set up between Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland.

1894 Guglielmo Marconi

The Italian inventor begins experiments on wireless telegraphy, seeing his invention as a means for point-to-point communication.

1906 Lee De Forest

American inventor develops the Audion vacuum tube for detecting and amplifying radio signals.

1910 Wireless Ship Act

Congress passes this act, requiring that all major ships be equipped with wireless radio.

1917 Amateur Radio Shutdown

At the request of the navy, the government closes down all amateur radio stations to ensure military security as the United States enters World War I.

1922 Commercial Radio

The first radio advertisements cause an uproar as people question the right to pollute the public airwaves with commercial messages.

1926 David Sarnoff

NBC is created, the first lasting network of radio stations; connected by AT&T long lines, the network broadcasts nationally and plays a prominent role in unifying the country.

1927 Radio Act of 1927

Radio stations are required to operate in the service of “public interest, convenience, or necessity.”

1928 William Paley

CBS is founded and becomes a competitor to NBC.

1930s The Golden Age of Radio

Living rooms are filled with music, drama, comedy, variety and quiz shows, weather forecasts, farm reports, and news.

1934 Federal Communications Act of 1934

This act allows commercial interests to control the airwaves.

1941 ABC

ABC is formed when RCA is forced to sell NBC-Blue.

1950s Radio Suffers

In the wake of TV’s popularity, radio suffers but is resurrected via rock-and-roll music formats and transistor radios.

1960s FM

Invented by Edwin Armstrong in the 1920s and early 1930s, a new format finally gains national popularity.

1990 Talk Radio

Talk radio becomes the most popular format, especially on AM stations.

1990s Internet Radio

In the second half of the decade, Internet radio—streaming either the content of an on-air station or a personalized radio station—takes hold.

1996 Telecommunications Act of 1996

This law effects a rapid, unprecedented consolidation in radio ownership across the United States.

2000 Pandora Internet Radio

Pandora Internet Radio launches in Oakland, California. Spotify, based in Europe, would start operating in the United States in 2011.

2002 Satellite Radio

A new format begins service.

2004 Podcasts

The combination of iPods and broadcasting creates podcasts, downloadable audio file programs posted to the Internet.

2014 Streaming Advances

According to ratings service Nielsen, Americans streamed over 70 billion songs in just the first half of 2014, well ahead of the same time period in 2013.

Click on the timeline above to see the full, expanded version.

187

Innovators in Wireless: Marconi, Fessenden, and De Forest

As the nineteenth century unfolded, inventors building on the earlier technologies continued improving wireless communication. New developments took wireless from narrowcasting (person-to-person or point-to-point transmission of messages) to broadcasting (transmission from one point to multiple listeners; also known as one-to-many communication).

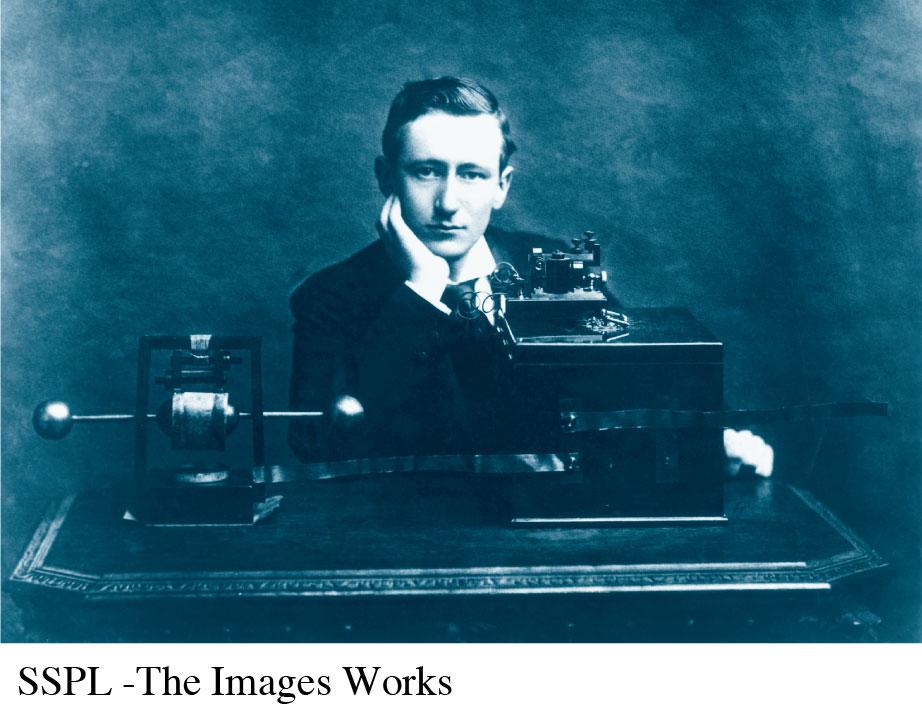

Marconi: The Father of Wireless Telegraphy

In 1894, a twenty-year-old, self-educated Italian engineer named Guglielmo Marconi read Hertz’s work. He quickly realized that developing a way to send high-speed messages over great distances would transform communication, commercial shipping, and the military. The young engineer set out to make wireless technology practical. After successfully figuring out how to build a wireless communication device that could send Morse code from a transmitter to a receiver, Marconi traveled to England in 1896. There, he received a patent on wireless telegraphy, a form of voiceless point-to-point communication.

In London the following year, the Italian inventor formed the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, later known as British Marconi. He began installing wireless technology on British naval and private commercial ships. This left other innovators to explore the wireless transmission of voice and music, later known as wireless telephony and eventually radio. In 1899, Marconi opened a branch in the United States nicknamed American Marconi. That same year, he sent the first wireless Morse code signal across the English Channel to France. In 1901, he relayed the first wireless signal from Cornwall, England, across the Atlantic Ocean to St. John’s, Newfoundland. History often cites Marconi as the “father of radio,” but Russian scientist Alexander Popov accomplished similar feats in St. Petersburg at the same time, and Nikola Tesla, a Serbian Croatian inventor who had immigrated to the United States, invented a wireless electrical device in 1892.

188

Fessenden: The First Voice Broadcast

Marconi had taken major steps in London and the United States. But it was Canadian engineer Reginald Fessenden who transformed wireless telegraphy into one-to-many communication. Fessenden is credited with providing the first voice broadcast. Formerly a chief chemist for Thomas Edison, he went to work for the U.S. Navy and eventually for General Electric (GE), where he focused on improving the frequency of wireless signals. Both the navy and GE were interested in the potential for voice transmission. On Christmas Eve in 1906, after GE built Fessenden a powerful transmitter, he gave his first public demonstration, sending his violin performance of “O Holy Night” and a reading of a Bible passage through the airwaves from his station at Brant Rock, Massachusetts, to an unknown number of shipboard operators off the Atlantic Coast.

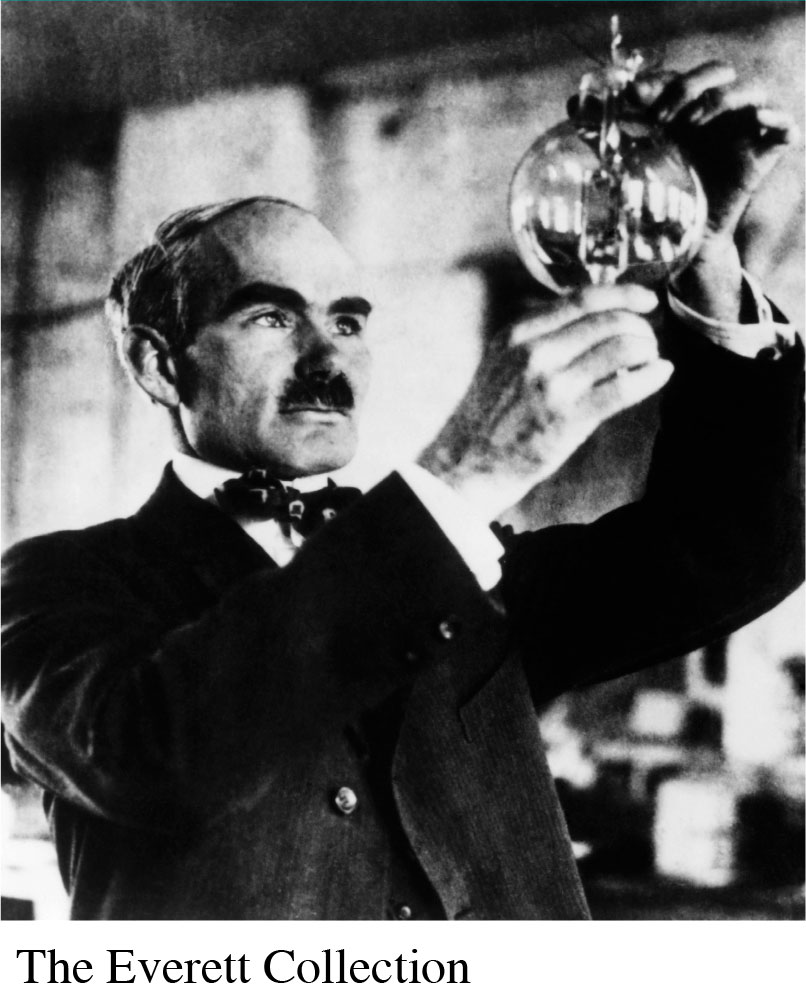

De Forest: Birthing Modern Electronics

American inventor Lee De Forest improved the usefulness of broadcasting by greatly increasing listeners’ ability to hear dots and dashes, and later speech and music, on a receiver. In 1906, he developed the Audion vacuum tube, which detected and amplified radio signals. The device was essential to the development of voice transmission, long-distance radio, and (eventually) television. Although De Forest had the patent for the Audion, he was accused in court and by fellow engineers of stealing others’ ideas, even when the court ruled in his favor.3 Many historians consider the Audion—which powered radios until the arrival of transistors and solid-state circuits in the 1950s—the origin of modern electronics.

189

In 1907, De Forest demonstrated his invention’s power and practical value by broadcasting a performance by Metropolitan opera tenor Enrico Caruso to his friends in New York. The next year, he and his wife, Nora, played records into a microphone from atop the Eiffel Tower in Paris; the signals were picked up by receivers up to five hundred miles away.

Early Regulation of Wireless/Radio

By the turn of the twentieth century, radio had become a new force in American life. Recognizing radio’s power to shape political opinion, economic dynamics, and military strategy and tactics, U.S. lawmakers moved to ensure U.S. control over the fledgling industry. With this goal in mind, legislators first defined radio as a shared resource for the public good. They then passed laws regulating how the public airwaves could be used and in what manner private businesses could take part in the industry.

Providing Public Safety

Because radio waves crossed state and national borders, legislators determined that broadcasting constituted a “natural resource”—a kind of interstate commerce—that should be regulated on the public’s behalf in the public’s best interests. Therefore, radio waves could not be owned, just licensed for use for a set period of time.

190

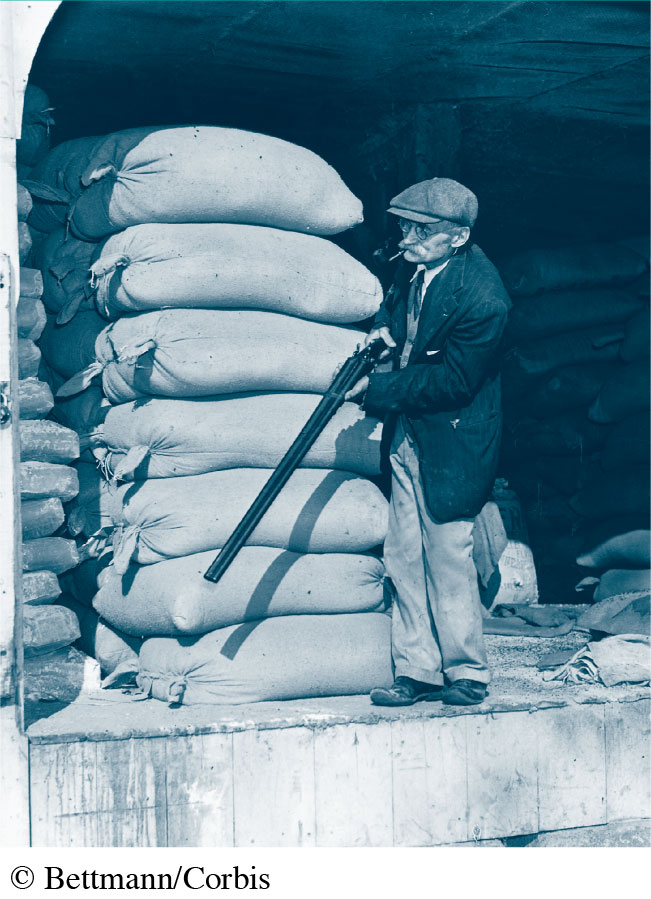

The first public safety rule came in 1910, when Congress passed the Wireless Ship Act. The law mandated that all major U.S. seagoing ships carrying more than fifty passengers and traveling more than two hundred miles off either coast be equipped with wireless equipment with a one-hundred-mile range. The importance of this act was underscored by the Titanic disaster in 1912, when over seven hundred passengers were saved by nearby ships responding to the passenger liner’s radio distress signals. In the wake of the Titanic tragedy, Congress passed the Radio Act of 1912. It required all radio stations on land or at sea to be licensed and assigned special call letters. The act helped to bring some order to the airwaves, which had been increasingly jammed with amateur radio operators. This act also formally adopted the SOS Morse-code distress signal.

Ensuring National Security

By 1915, more than twenty American companies sold wireless point-to-point communication systems, primarily for use in ship-to-shore communication. American Marconi (a subsidiary of British Marconi) was the biggest of these companies. But with World War I erupting in Europe, the U.S. Navy questioned the wisdom of allowing a foreign-controlled company to wield so much power over communication. When the United States entered the war in 1917, the government closed down all amateur radio operations, took control of key radio transmitters, and blocked British Marconi from purchasing radio equipment from General Electric. These moves addressed concerns about national security. They also enabled the United States to reduce Britain’s influence over communication and tightened U.S. control over the emerging wireless infrastructure.

RCA: The Formation of an American Radio Monopoly

Some members of Congress, along with some business leaders, opposed federal legislation granting the government or the navy a radio monopoly. To secure a place in the fast-evolving industry, GE proposed a plan by which it would create a private-sector monopoly—a privately owned company that would have the government’s approval to dominate the radio industry. In 1919, the plan was accepted by the powers that be at both GE and the U.S. Navy—the government branch most prominently fighting for control of the radio industry in America. GE founded the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) to purchase and pool patents from the navy, AT&T, GE, the former American Marconi, and other companies to ensure U.S. control over the manufacture of radio transmitters and receivers. Under the various agreements, AT&T made most transmitters; GE (and later Westinghouse) made radio receivers; and RCA administered patents, collected royalties, and redistributed them to the others.4

191

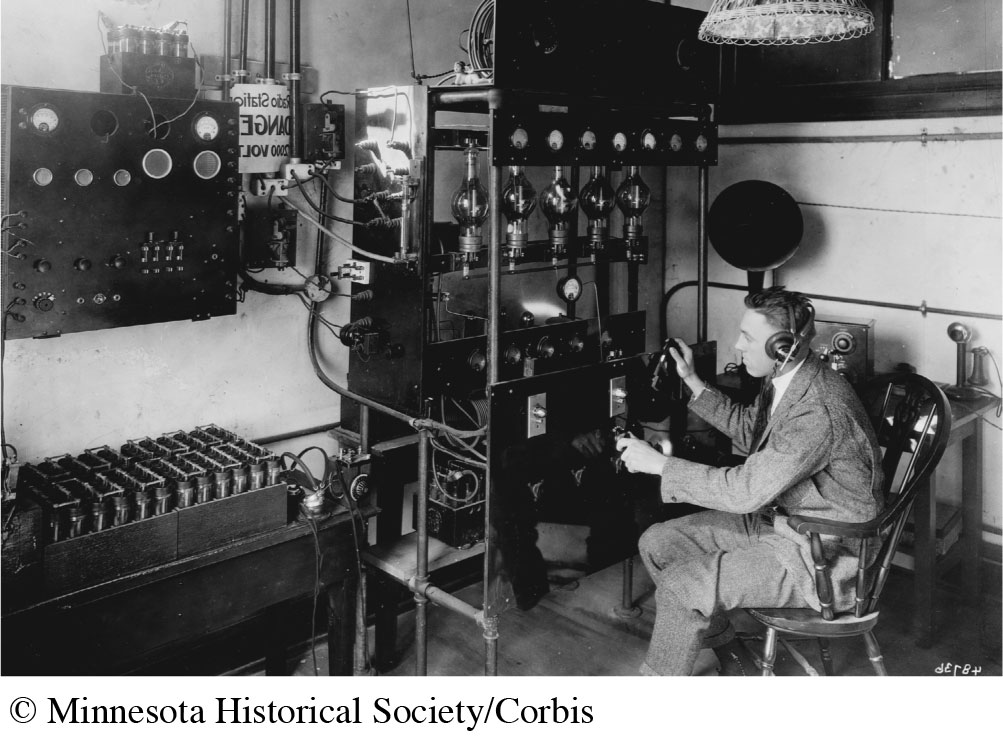

KDKA: The First Commercial Radio Station

With the advent of the United States’ global dominance in mass communication, many people became intrigued by radio’s potential. Amateur stations popped up in places like San Jose, California; Medford, Massachusetts; New York; Detroit; and Pierre, South Dakota. The best-known early station was begun by an engineer named Frank Conrad, who worked for GE’s rival, Westinghouse Electric Company. In 1916, he set up a radio studio above his Pittsburgh garage by placing a microphone in front of a phonograph. Conrad broadcast music and news to his friends (whom he supplied with receivers) two evenings a week on experimental station 8XK. When a Westinghouse executive got wind of Conrad’s activities in 1920, he established KDKA, generally regarded as the first commercial (profit-based) broadcast station. The following year, the U.S. Commerce Department officially licensed five radio stations for operation; by early 1923, more than six hundred commercial and noncommercial stations were operating. Just two years later, a whopping 5.5 million radio sets were in use across America—made by companies such as GE and Westinghouse and costing about $55 ($664 in today’s dollars). Radio was officially a mass medium.

The Networks

With the establishment of the private sector’s involvement in radio, the groundwork was laid for radio to take off as a business, which would enable commercial station owners (and the advertisers that funded them) to reach more listeners more efficiently than ever. The radio network arose: a cost-saving operation that links a group of affiliate or subsidiary broadcast stations that share programming produced at a central location. (At that time, stations were linked through special phone lines; today, they’re linked through satellite relays.)

The network system enabled stations to control program costs and avoid unnecessary duplication of content creation. Simply put, it was cheaper to produce programs at one station and broadcast them simultaneously over multiple owned or affiliated stations than for each station to generate its own programs. Networks thus brought the best musical, dramatic, and comedic talent to one place, where programs could be produced and then distributed all over the country. This new business model concentrated control of radio in the hands of a few corporate players, all of whom jockeyed for additional power.

192

AT&T: Making a Power Grab

The shift toward networks began in 1922, when RCA’s partnership with AT&T began to unravel. In a major power grab, AT&T, which already had a government-sanctioned monopoly in the telephone business, decided to break its RCA agreements in an attempt to monopolize radio. Identifying the new medium as the “wireless telephone,” AT&T argued that broadcasting was merely an extension of its control over the telephone. The corporate giant complained that RCA had gained too much power. In violation of its early agreements with RCA, AT&T began making and selling its own radio receivers.

That same year, AT&T started WEAF (now WNBC) in New York, the first radio station to regularly sell commercial time to advertisers. Advertising, company executives reasoned, would ensure profits long after radio-set sales had saturated the consumer market. AT&T claimed that under the RCA agreements, it had the exclusive right to sell ads, which AT&T called toll broadcasting. Most people in radio at the time recoiled at the idea of using the medium for advertising, viewing the medium instead as a public information service. But executives remained riveted by the potential of radio ads to enhance profits.

Still, the initial motivation behind AT&T’s toll broadcasting idea was to dominate radio. Through its agreements with RCA, AT&T retained the rights to interconnect the signals between two or more radio stations via telephone wires. By the end of 1924, AT&T had interconnected twenty-two stations in a network to air a talk by President Calvin Coolidge. Some of these stations were owned by AT&T, but most simply consented to become AT&T “affiliates,” agreeing to air the phone company’s programs.

Seeing AT&T’s success, GE, Westinghouse, and RCA launched a competing network. AT&T promptly denied them access to its telephone wires, so the new network used inferior telegraph lines to connect its stations. In 1925, the Justice Department, irritated by AT&T’s power grab, redefined patent agreements. AT&T received a monopoly on providing the wires, known as long lines, to interconnect stations nationwide. In exchange, AT&T agreed to sell its network to RCA for $1 million and promised not to reenter broadcasting for eight years.

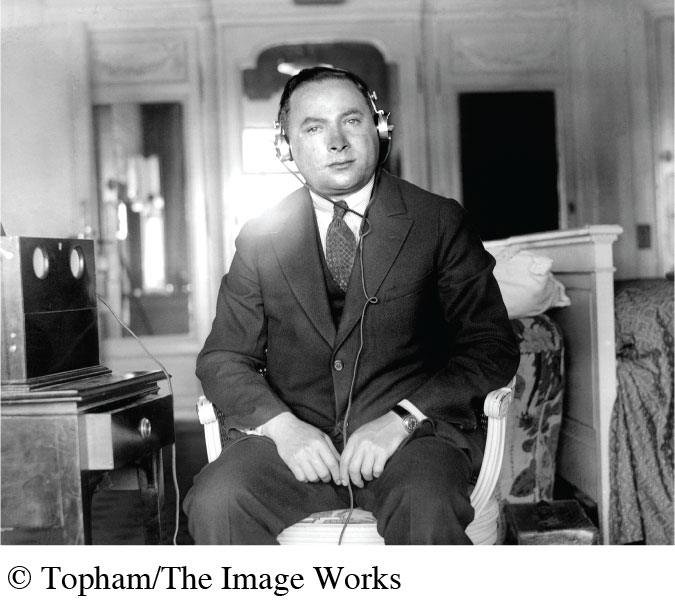

NBC: RCA Forms a Network

The commercial rewards of the network and affiliate system continued to excite executives’ imaginations. For example, after RCA bought AT&T’s telephone line–based radio network, David Sarnoff, RCA’s general manager, created a new subsidiary in September 1926 called the National Broadcasting Company (NBC). NBC’s ownership was shared by RCA (50%), General Electric (30%), and Westinghouse (20%). The former group of AT&T stations became known as NBC-Red. The network RCA, GE, and Westinghouse had already been building became NBC-Blue. By 1933, NBC-Red would have twenty-eight affiliates; NBC-Blue, twenty-four.

193

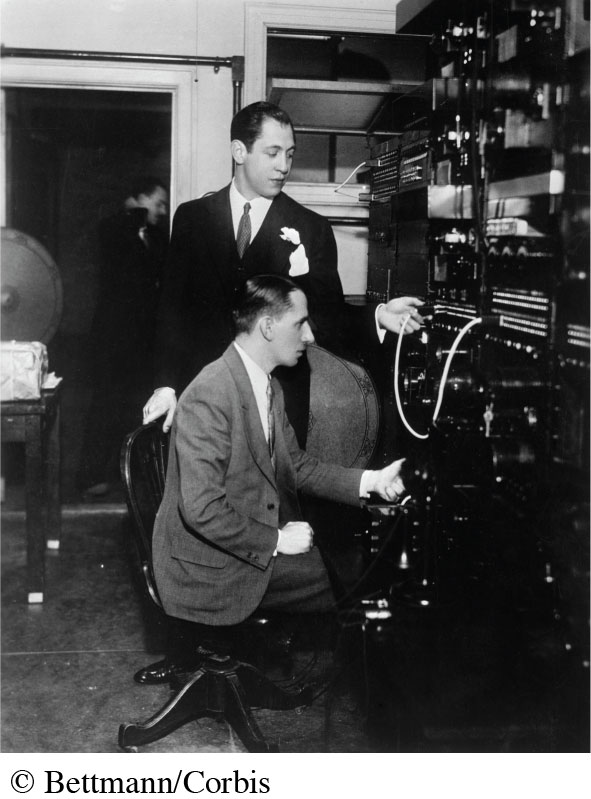

CBS: A Rival Network Challenges NBC

The network and affiliate system under RCA/NBC thrived throughout most of the 1920s and brought Americans together as never before to participate in the big events of the day. For example, when aviator Charles Lindbergh returned from the first solo transatlantic flight in 1927, an estimated twenty-five to thirty million people listened to his welcome-home party on the six million radio sets then in use. At the time, it was the largest shared audience experience in the history of any mass medium.

During this decade, competition stiffened further within the industry. For instance, in 1928, William Paley, the twenty-seven-year-old son of a Philadelphia cigar company owner, bought the Columbia Phonograph Company and built it into a network later renamed the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS). Unlike NBC, which actually charged its affiliates up to $96 a week for the privilege of carrying its programming, CBS paid affiliates as much as $50 an hour to carry its programs. By 1933, Paley’s efforts had netted CBS more than ninety affiliates, many of which had defected from NBC. Paley also concentrated on developing news programs and entertainment shows, particularly soap operas and comedy-variety series. To that end, CBS raided NBC not just for affiliates but also for top talent, such as comedian Jack Benny and singer Frank Sinatra. In 1949, CBS finally surpassed NBC as the highest-rated network on radio.

The Radio Act of 1927

The growing concentration of power in the network and affiliate system raised a red flag for government leaders. Throughout the 1920s to early 1940s, lawmakers would enact many regulations aimed at regaining control over the industry. In particular, by the late 1920s, the government had become alarmed by RCA/NBC’s growing influence over radio content. Moreover, as radio moved from narrowcasting to broadcasting, battles among various players over such issues as more frequency space and less channel interference heated up. Manufacturers, engineers, station operators, network executives, and the listening public demanded action to address their conflicting interests. Many wanted more sweeping regulation than the simple licensing function granted under the Radio Act of 1912, which gave the Commerce Department little power to deny a license or to unclog the airwaves.

194

To restore order, Congress passed the Radio Act of 1927, which introduced a pivotal new principle: Licensees did not own their channels but could use them as long as they operated to serve the “public interest, convenience, or necessity.” To oversee licenses and negotiate channel problems such as too many stations trying to air on too few frequencies, the 1927 act created the Federal Radio Commission (FRC), whose members were appointed by the president.

Although the FRC was intended as a temporary committee, it grew into a powerful regulatory agency. With passage of the Federal Communications Act of 1934, the FRC became the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Its jurisdiction covered not only radio but also the telephone and the telegraph (and later television, cable, and the Internet). More significantly, by this time Congress and the president had sided with the already-powerful radio networks and acceded to a system of advertising-supported commercial broadcasting as best serving the “public interest, convenience, or necessity,” overriding the concerns of educational, labor, religious, and citizen broadcasting advocates.

In 1941, an activist FCC set out to break up what it saw as overly large and powerful networks, which led to a Supreme Court ruling forcing RCA to sell NBC-Blue. The divested enterprise became the American Broadcasting Company (ABC). Such government crackdowns brought long-overdue reforms to the radio industry. However, they came too late to prevent considerable damage to noncommercial radio.

The Golden Age of Radio

From the late 1920s to the 1940s, radio basked in a golden age marked by a proliferation of informative and entertaining programs (such as weather forecasts, farm reports, news, music, dramas, quiz shows, variety shows, and comedies). This diversity of programming shaped—and was shaped by—American culture. It also paved the way for programs that Americans would later enjoy on television, as NBC, CBS, and ABC created television networks in the late 1940s and 1950s.

Early Radio Programming

In the early days of radio, only a handful of stations operated in most large radio markets. Through the networks they were affiliated with, these stations broadcast a variety of programs into listeners’ homes (and in some cases, their cars). People had favorite evening programs, usually fifteen minutes long. After dinner, families gathered around the radio to hear comedies, dramas, public service announcements, and more. Popular programs included Amos ‘n’ Andy (a serial situation comedy), The Shadow (a mystery drama), The Lone Ranger (a western), The Green Hornet (a crime drama), and Fibber McGee and Molly (a comedy), as well as the “fireside chats” regularly presented by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

195

Variety shows featuring musical performances and comedy skits planted the seeds for popular TV variety shows that would come later, such as the Ed Sullivan Show. Quiz shows (including The Old Time Spelling Bee) introduced Americans to the thrill of competition. These radio programs set the stage for later competition-based TV shows, ranging from The Price Is Right and Who Wants to Be a Millionaire to reality-based shows such as Survivor, Fear Factor, Project Runway, and Top Chef.

Dramatic programs, mostly radio plays broadcast live from theaters, would inspire later TV dramas, including “soap operas.” (The term came into use after Colgate-Palmolive began selling its soap products on dramas it sponsored.) Another type of program, the serial, introduced the idea of continuing story lines from one day to the next—a format soon adopted by soap operas and some comedy programs.

Radio as Cultural Mirror

Radio programs powerfully reflected shifts in American culture, including attitudes about race and levels of tolerance for stereotypes. For example, the situation comedy Amos ‘n’ Andy was based on the conventions of the nineteenth-century minstrel show and featured black characters stereotyped as shiftless and stupid. Created as a blackface stage act by two white comedians, Charles Correll and Freeman Gosden, the program was criticized as racist by some at the time; however, NBC and the program’s producers claimed that Amos ‘n’ Andy was as popular among black audiences as it was among white listeners.5

Early radio research estimated that the program aired in more than half of all radio homes in the nation during the 1930–31 season, making it the most popular radio series in history. In 1951, Amos ‘n’ Andy made a brief transition to television, after Correll and Gosden sold the rights to CBS for $1 million. It became the first TV series to have an all-black cast. But amid a strengthening Civil Rights movement and a formal protest by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which argued that “every character is either a clown or a crook,” CBS canceled the program in 1953.6

The Authority of Radio

In addition to reflecting evolving cultural beliefs, radio increasingly shaped them—in part by being perceived by listeners as the voice of authority. The adaptation of science-fiction author H. G. Wells’s War of the Worlds (1898) on the radio series Mercury Theatre on the Air provides the most notable example of this. Considered the most famous single radio broadcast of all time, War of the Worlds was produced and hosted by Orson Welles, who also narrated it. On Halloween eve in 1938, the twenty-three-year-old Welles aired the Martian-invasion story in the style of a contemporary radio news bulletin. For people who missed the opening disclaimer, the program sounded like an authentic news report, with apparently eyewitness accounts of battles between Martian invaders and the U.S. Army.

196

The program triggered a panic among some listeners. In New Jersey, some people walked through the streets with wet towels wrapped around their heads for protection against deadly Martian heat rays. In New York, young men reported to their National Guard headquarters to prepare for battle. Across the nation, calls from terrified citizens jammed police switchboards. The FCC called for stricter warnings both before and during programs imitating the style of radio news.