The Evolution of the Hollywood Studio System

By the 1910s, movies had become a major industry, and entrepreneurs developed many tactics for controlling it—including monopolizing patents on film-related technologies and dominating the “three pillars” of the movie business: production (making movies), distribution (getting films into theaters), and exhibition (playing films in theaters). Controlling those three parts of an industry achieves vertical integration. In the film business, it means managing the entire moviemaking process—from the development of an idea to the screening of the final product before an audience. The resulting concentration of power gave rise to the studio system, in which creative talent was firmly controlled by certain powerful studios. Five vertically integrated movie studios, sometimes referred to as the Big Five, made up this new film oligopoly (a situation in which an industry is controlled by just a few firms): Paramount, MGM, Warner Brothers, Twentieth Century Fox, and RKO. An additional three studios, sometimes called the Little Three—Columbia, Universal, and United Artists—did not own chains of theaters but held powerful positions in movie production and distribution.

Edison’s Attempt to Control the Industry

Among the first to try his hand at dominating the movie business and reaping its profits, Thomas Edison formed the Motion Picture Patents Company, known as the Trust, in 1908. A cartel of major U.S. and French film producers, the company pooled film-technology patents, acquired most major film distributorships, and signed an exclusive deal with George Eastman, who agreed to supply stock film only to Trust-approved theater companies.

However, some independent producers refused to bow to the Trust’s terms. These producers abandoned film production centers in New York and New Jersey and moved to Cuba; Florida; and ultimately Hollywood, California. In particular, two Hungarian immigrants—Adolph Zukor (who would eventually run Paramount Pictures) and William Fox (who would found the Fox Film Corporation, later named Twentieth Century Fox)—wanted to free their movie operations from the Trust’s tyrannical grasp. Zukor’s early companies figured out ways to bypass the Trust. A suit by Fox, a nickelodeon operator?-turned-film distributor, resulted in the Trust’s breakup for restraint-of-trade violations in 1917.

225

A Closer Look at the Three Pillars

Ironically, film entrepreneurs like Zukor who fought the Trust realized they could control the film industry themselves through vertical integration. The three pillars of vertical integration occur in a specific sequence: First, movies are produced. Next, copies are distributed to people or companies who get them out to theaters. Finally, the movies are exhibited in theaters. But even as power through vertical integration became concentrated in just a few big studios, other studios sought to dominate one or another of the three pillars. This competition sparked tension between the forces of centralization and those of independence.

Production

A major element in the production pillar is the choice of actors for a particular film. This circumstance created an opportunity for some studios to gain control using tactics other than Edison’s pooling of patents. Once these companies learned that audiences preferred specific actors to anonymous ones, they signed exclusive contracts with big-name actors. In this way, the studio system began controlling the talent in the industry. For example, Adolph Zukor hired a number of popular actors and formed the Famous Players Film Company in 1912. One Famous Players performer was Mary Pickford, who became known as “America’s Sweetheart” for her portrayal of spunky and innocent heroines. Pickford so elevated film actors’ status that in 1919, she broke from Zukor to form her own company, United Artists. Actor Douglas Fairbanks (her future husband) joined her, along with comedian-director Charlie Chaplin and director D. W. Griffith.

Although United Artists represented a brief triumph of autonomy for a few powerful actors, by the 1920s the studio system had solidified its control over all creative talent in the industry. Pioneered by director Thomas Ince and his company, Triangle, the system constituted a kind of assembly line for moviemaking talent: Actors, directors, editors, writers, and others all worked under exclusive contracts for the major studios. Ince also designated himself the first studio head, appointing producers to handle hiring, logistics, and finances so that he could more easily supervise many pictures at once. The studio system proved so efficient that major studios were soon producing new feature films every week. Pooling talent, rather than patents, turned out to be a more ingenious tactic for movie studios seeking to dominate film production.

226

Distribution

Whereas there were two main strategies for controlling the production pillar of moviemaking (pooling patents or pooling talent), studios seeking power in the industry had more options open to them for controlling distribution. One early effort to do so came in 1904, when movie companies provided vaudeville theaters with films and projectors on a film exchange system. In return for their short films, shown between live acts in the theaters, movie producers received a small percentage of the vaudeville ticket-gate receipts.

Edison’s Trust used another tactic: withholding projection equipment from theater companies not willing to pay the Trust’s patent-use fees. However, as with the production of film, independent film companies looked for distribution strategies outside of the Trust. Again, Adolph Zukor led the fight, developing block booking. Under this system, movie exhibitors who wanted access to popular films with big stars like Mary Pickford had to also rent new or marginal films featuring no stars. Although this practice was eventually outlawed as monopolistic, such contracts enabled the studios to test-market possible up-and-coming stars at little financial risk.

As yet another distribution strategy, some companies marketed American films in Europe. World War I so disrupted film production in Europe that the United States stepped in to fill the gap—eventually becoming the leader in the commercial movie business worldwide. After the war, no other nation’s film industry could compete economically with Hollywood. By the mid-1920s, foreign revenue from U.S. films totaled $100 million. Even today, Hollywood dominates the world market for movies.

Exhibition

Companies could gain further control of the movie industry by finding ways to get more people to buy more movie tickets. Innovations in exhibition (such as construction of more inviting theaters) transformed the way people watched films and began attracting more middle- and upper-middle-class viewers.

Initially, Edison’s Trust tried to dominate exhibition by controlling the flow of films to theater owners. If theaters wanted to ensure they had films to show their patrons, they had to purchase a license from the Trust and pay whatever price it asked. But after the Trust collapsed, emerging studios in Hollywood came up with their own ideas for controlling exhibition and making certain the movies they produced were shown. When industrious theater owners began forming film cooperatives to compete with block-booking tactics, producers like Zukor conspired to buy up theaters. Zukor and the heads of several major studios understood that they did not have to own all the theaters to ensure that their movies would be shown. Instead, the major studios needed to own only the first-run theaters (about 15% of the nation’s theaters). First-run theaters premiered new films in major downtown areas in front of the largest audiences and generated 85 to 95 percent of all film revenue.

227

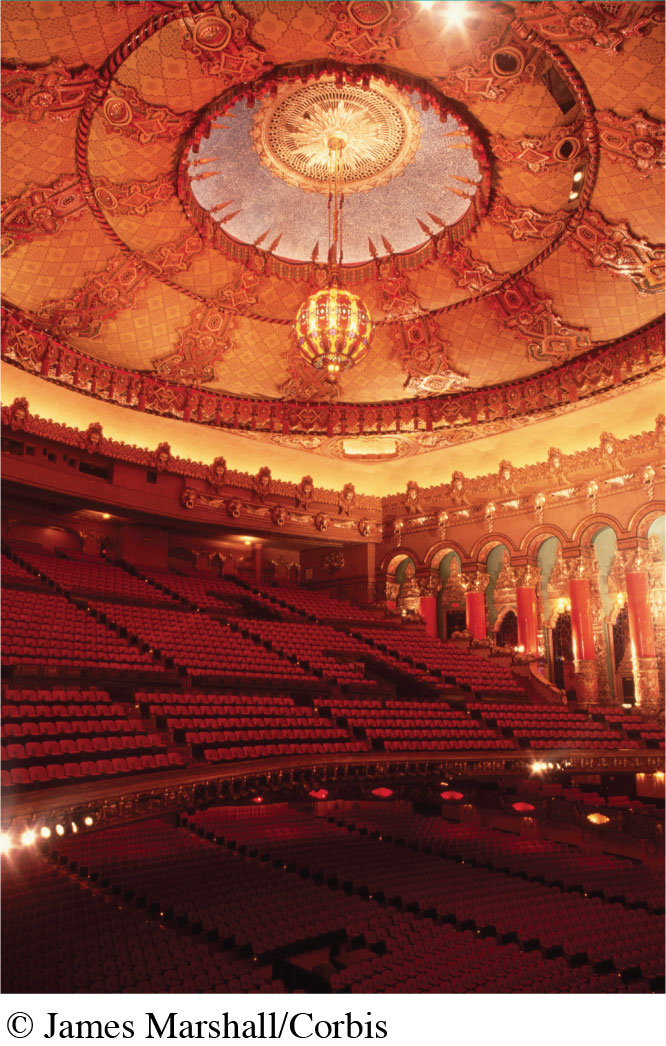

The studios quickly realized that to earn revenue from these first-run theaters, they would have to draw members of the middle and upper-middle classes to the movies. With this goal in mind, they built movie palaces, full-time single-screen theaters that provided a more enjoyable and comfortable movie-viewing environment. In 1914, the three-thousand-seat Strand Theatre, the first movie palace, opened in New York.

Another major innovation in exhibition was the development of mid-city movie theaters. These theaters—built in convenient locations near urban mass-transit stations—attracted city dwellers as well as the initial wave of people who had moved to city outskirts in the 1920s and commuted into work from the suburbs. This strategy is alive and well today, as multiplexes and megaplexes featuring many screens (often fourteen or more), upscale concession services, stadium-style seating, digital projection and sound, 3-D capabilities, and giant IMAX screens lure middle-class crowds to interstate highway crossroads (see “Converging Media Case Study: Movie Theaters and Live Exhibition” on pages 244–245).