1.7 Environmental ethics extends moral responsibilities to the environment

1.7–

Science has taught us much about the natural world, the environment, and the challenges that we face in managing our resources. Science can also lead to technologies and policies used to avoid or repair environmental harm. However, science is silent about the environmental decisions you and I need to make as a society, which can have economic consequences, and about those things we call truth, beauty, right, and wrong. It does not instruct us on how we should treat living systems, as individuals or societies, nor does it tell us what value we should place on the natural world. For answers to questions such as these, we need to look elsewhere.

environmental ethics The branch of philosophy that concerns the moral responsibilities of humans with regard to the environment.

The area of philosophy that concerns the moral relationship of humans to the environment, including all of its human and nonhuman parts, is called environmental ethics. Our views about the gravity of environmental problems and the need for solutions to them will emerge from ethical worldviews (Figure 1.26).

In his push for relocating tanneries, which ethical view was Benjamin Franklin reflecting: ecocentric, biocentric, or anthropocentric?

Worldviews

anthropocentric Human-

22

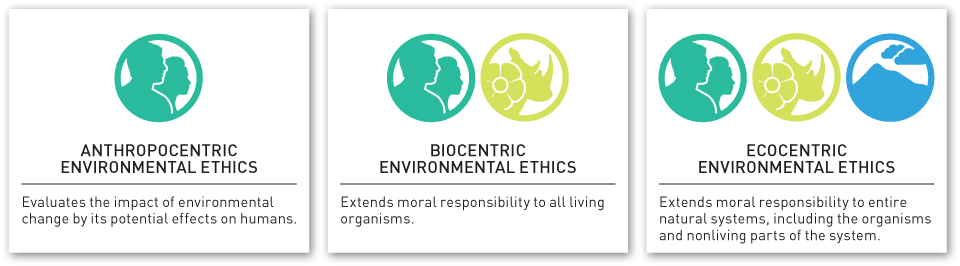

Perspectives on nature that place humans at the center are called anthropocentric, or human-

biocentric Centered on life in all its forms; for example, biocentric environmental ethics extends moral obligation to all life.

ecocentric Centered on entire ecosystems; for example, ecocentric environmental ethics extends moral obligation to the nonliving components of the environment, emphasizing the integrity of whole natural systems.

By contrast, the biocentric view emphasizes the effects of actions on all living organisms. From a biocentric perspective, cruelty to animals, needless destruction of plants, and, by extension, extinction of species are morally wrong because organisms have intrinsic value. The ecocentric environmental ethic extends moral obligation beyond organisms to the nonliving components of the environment and emphasizes the integrity of whole natural systems. For example, a biocentric view would posit that if a site is disturbed by mining, the native species that had occupied the site before the disturbance should be restored. By contrast, an ecocentric position would be that the entire landscape should be restored to its original form, including depth and texture of topsoil, patterns of drainage channels, and so forth.

land ethic An ecocentric system of environmental ethics proposed by Aldo Leopold to promote the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biological community.

23

Aldo Leopold (1887–

Environmental Ethics in Action

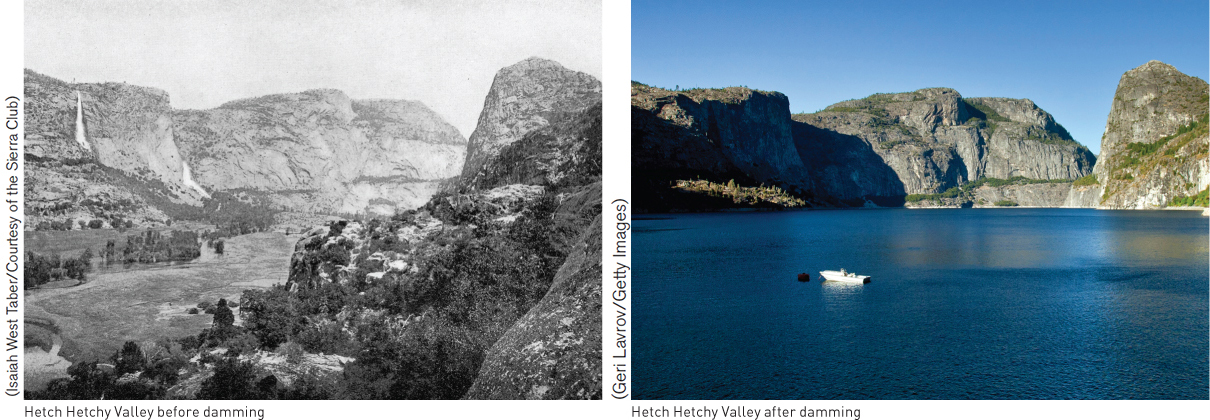

One of the most famous clashes of environmental ethics involved the creation of a reservoir in the Hetch Hetchy Valley, a part of Yosemite National Park just north of the more famous Yosemite Valley (Figure 1.27). After John Muir first visited Hetch Hetchy in 1872, he wrote about it as a second Yosemite and campaigned relentlessly for the preservation of both it and the Yosemite Valley on the basis of an ecocentric environmental ethic. In 1890 Yosemite National Park, which included both valleys, was established. However, James Phelan, the mayor of San Francisco, proposed damming the Hetch Hetchy Valley to create a reservoir to supply the water needs of the city. He found an ally in Gifford Pinchot, the chief of the U.S. Forest Service, whose anthropocentric conservation ethic emphasized the wise use of natural resources for the benefit of the largest number of people.

What does a person’s opinion about whether or not Hetch Hetchy should be restored to its wild state reveal about his or her environmental ethics?

Battle lines were drawn. Muir and the Sierra Club conducted a national campaign to defend the valley from the damming. Muir’s ecocentric ethics represented the management philosophy of the National Park Service, which is dedicated to the goal of preserving intact wild lands. On the other side, Pinchot’s position represented the U.S. National Forest, which is dedicated to managing the national forests for multiple uses, including economic gain. Pinchot won the battle, and in 1913 Congress authorized damming the valley. However, the struggle continues to this day as the Sierra Club hopes to remove the dam and restore the Hetch Hetchy Valley to its natural state.

Environmental Justice

environmental justice The fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people in the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

Historically, environmental burdens, such as the location of waste dumps or highway systems, have been borne mainly by those most disadvantaged, because of socioeconomic status, race, or ethnicity. The environmental justice movement arose in the United States in response to these inequities.

The birth of the environmental justice movement is generally associated with a 1982 protest against a proposed chemical landfill in poor, mainly African American, Warren County, North Carolina. During the six weeks of protest against the landfill, 500 people were arrested (Figure 1.28). Although the toxic waste was eventually deposited at the proposed site, the protests sensitized the general public and policy makers, inspiring a movement for fairness in environmental decisions. Pressures for environmental justice pushed the major environmental organizations, such as the Sierra Club, to place issues arising from the siting of landfills, toxic waste dumps, and other sources of pollution alongside their traditional focus on preservation of wilderness and other natural areas.

24

Why did it take nearly a century after the founding of Yosemite National Park for organizations like the Sierra Club to support the concept of environmental justice?

Religious and Cultural Perspectives

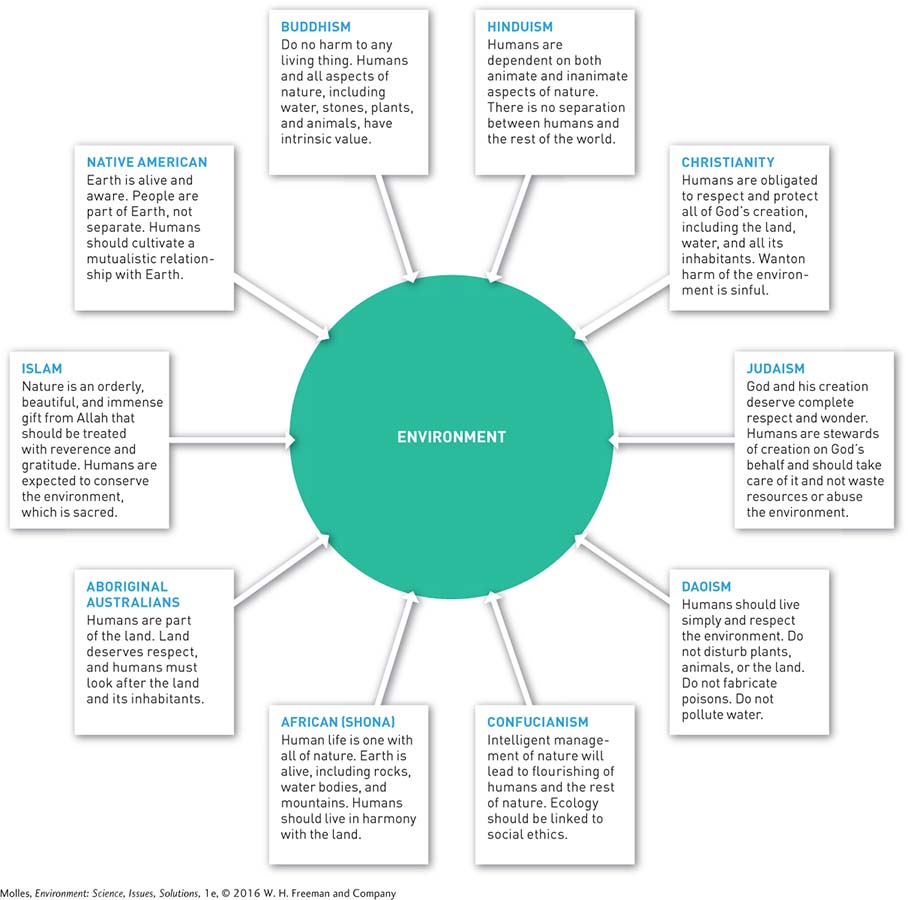

Your religious beliefs and cultural background will undoubtedly shape your own particular take on environmental issues. Nevertheless, a cursory review of belief systems around the world shows that people everywhere place value on protecting the environment (Figure 1.29). If cultures have converged on the conclusion that we should care for the environment, how do we explain the environmental damage that we can see around the world?

25

In some cases, harm to the environment may be the result of people, with few alternatives, trying to make a living or simply trying to survive. Environmental harm may also result from incomplete knowledge. For example, the manufacturers of the CFCs that have depleted the ozone layer did not know that their product would endanger this protective layer. In other cases, harm to the environment results from the practice of pursuing economic gain, while disregarding the environmental impacts of that activity. In addition, harm to one part of the environment must often be weighed against the benefits to another part of the environment or to human well-

Think About It

What adjustments in moral responsibilities must be made in order to shift from an anthropocentric ethic to an ecocentric ethic? Which is better for human welfare? Does taking a short-

term versus long- term frame of reference make a difference? What is the relationship of the environmental justice movement and the various other environmental ethics perspectives?

What is the significance of values in addressing environmental issues? What are the limitations?