4.5 Global species richness results from a balance between speciation and extinction

108

Just as the number of species on islands is largely determined by rates of immigration and extinction, the number of species on Earth as a whole is determined by the relative rates at which new species form and existing ones become extinct. In Chapter 3, we discussed patterns of extinction over time, including how human activity is increasing extinction rates to levels suggesting a mass extinction. Here, we examine extinction’s opposite: the process by which new species arise.

Allopatric Speciation

What factors could keep two geographically isolated populations from diverging genetically?

speciation An evolutionary process by which new species arise.

allopatric (geographic) speciation A process by which new species are formed that occurs as the result of the division of a population into two geographically separate populations; over time, genetic differences arise and accumulate in the two separate populations, eventually leading to reproductive isolation.

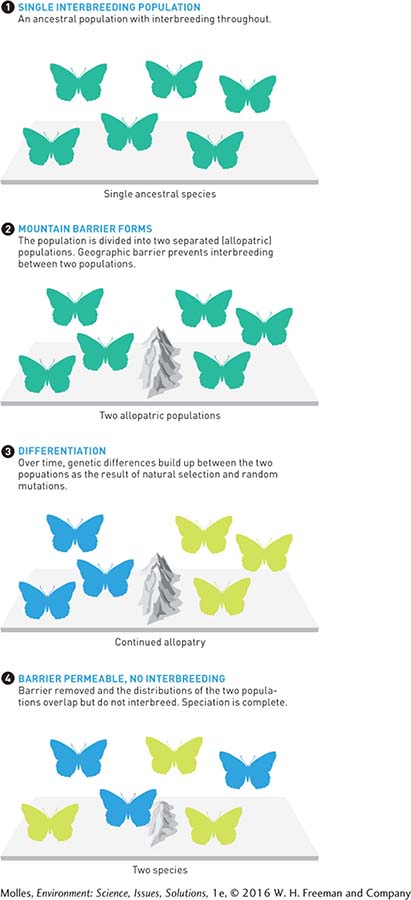

The evolutionary process by which new species arise is called speciation. Evolutionary biologists have proposed several ways in which new species may form. The most common form of speciation, however, appears to occur when a geographic barrier, such as a river, canyon, or mountain range, divides a single population into separate subpopulations in a process called allopatric, or geographic, speciation. Because the separated organisms cannot cross the geographic barrier to mate, genetic differences between the two populations can gradually accumulate either because the separated populations adapt to different environmental conditions or because of random mutations. When the populations become so different genetically or behaviorally that they no longer interbreed, they have become two separate species (Figure 4.17).

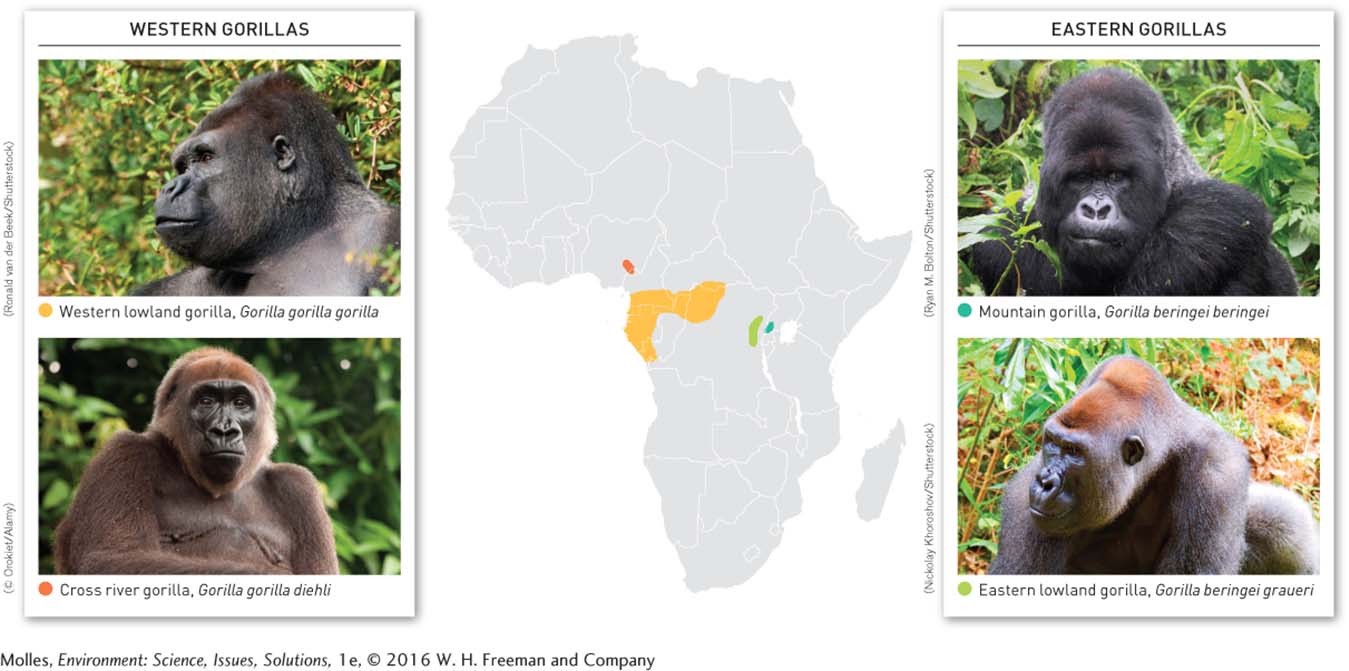

Gorillas provide a good example of allopatric speciation. The two recognized species—

109

Sympatric Speciation

People all around the world are concerned about survival of gorillas. What are the possible sources of this concern?

New species can also arise without geographic isolation, in a process called sympatric speciation. Sympatric speciation may follow ecological or behavioral separation of two subpopulations of a species that use different habitats or foods. If two subpopulations of a species use different criteria for choosing mates, they may also diverge without geographic isolation. Sympatric speciation can also occur through polyploidy, an increase in the number of sets of chromosomes, either by doubling the number of sets within a species lineage or by doubling the number of sets of chromosomes following hybridization between two closely related species. Polyploidy has been an important mechanism for sympatric speciation in plants. The evidence for sympatric speciation among animals is weaker. However, this is an area of active current research.

Think About It

Some birds, originally described as separate species because they differ greatly in color pattern and some aspects of behavior, have since been combined under a single species name because members of the two populations have been found to interbreed in nature and produce fully fertile offspring. What is the scientific justification for considering these physically distinct populations as members of the same species?

If extinction has been a natural process throughout the history of life on Earth, why are environmental scientists working to reduce the present threats of extinction?

110

4.1–4.5 Science: Summary

Species diversity is a function of the number of species—

Diversity is shaped by a number of factors. Species richness on islands, determined by species immigration and extinction, is usually lower compared with similar-

Species diversity is also the product of evolution. During allopatric speciation, a population is divided into two geographically separate populations. The two separated populations then accumulate differences over time, becoming separate species when they no longer interbreed. During sympatric speciation, new species form without geographic isolation.