4.7 Valuable services of ecosystems are threatened

Beyond losing the aesthetic benefits of nature, what are the consequences of losing an ecosystem? In the late 1990s, a panel of 11 ecologists, led by Gretchen Daily of Stanford University, identified a long list of goods and services that humans derive from natural ecosystems. The goods can be readily assigned economic value because they are regularly bought and sold—

Many of those goods are already being threatened by unsustainable harvesting (see Chapter 8). According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, one-

113

ecosystem services

Aspects of ecosystem structure and function that have economic, social, or cultural value to human populations (e.g., flood control by wetlands or water purification by forest and river ecosystems).

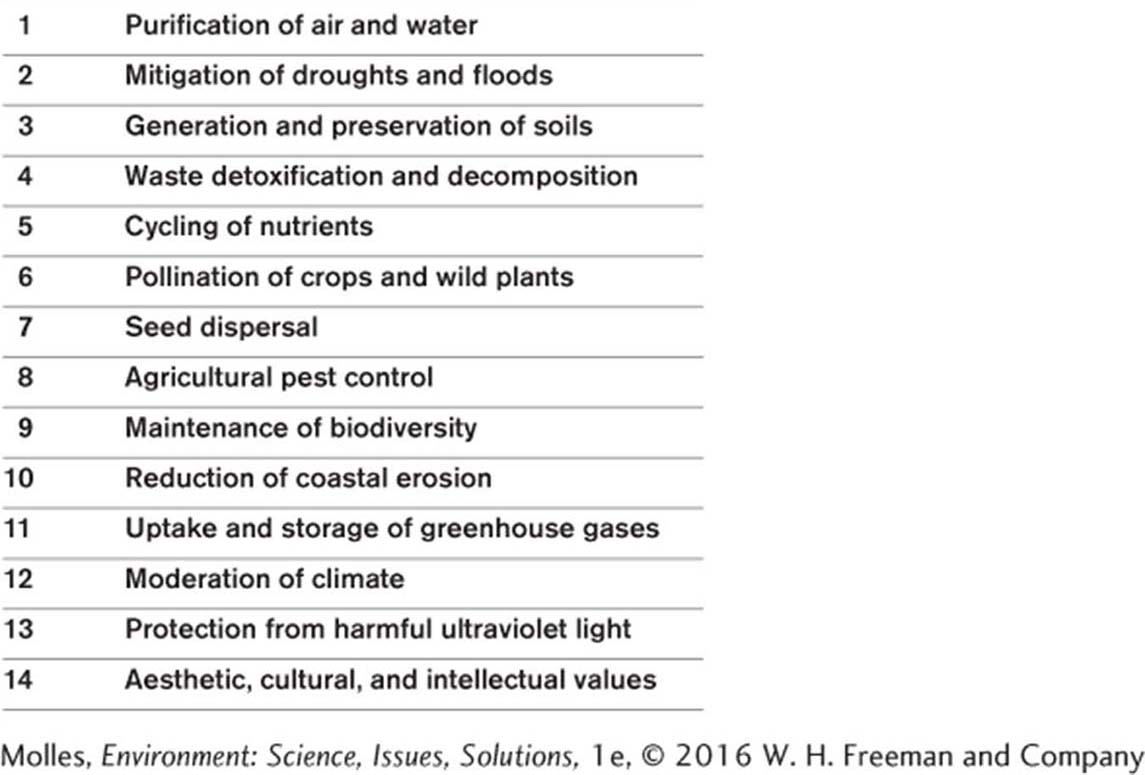

In addition to goods, ecosystems provide many services to the local and global environment: Plant roots and soil filter water, trees filter the air, mangrove and coastal forests provide flood control. These ecosystem services have economic, social, or cultural value to human populations (Table 4.1). For example, wild native insects provide ecological services such as pollination, control of native herbivore pests, and even recreation. A 2006 estimate put the annual value of ecological services provided by insects at $57 billion in the United States alone. However, these services are threatened by factors such as the overuse of pesticides and herbicides. For instance, colony collapse disorder, a mysterious condition that has been wiping out approximately 10% of honeybee colonies each year, has been linked to neonicotinoid pesticides (insecticides chemically similar to nicotine), although other factors may be involved.

Other animals may control pest insect populations: A colony of 30,000 southeastern bats in Florida eats more than 15 tons of mosquitoes each year. Historically, bats have been persecuted by humans who have dynamited, poisoned, and shot them. Today, the biggest threat to bats’ survival comes from a fungal disease called white nose syndrome, which was likely spread by recreational cavers and has killed more than 5.7 million bats in eastern North America.

Some have criticized attempts to put an economic value on ecosystem services. What are some of the sources of such criticisms?

Functioning ecosystems can even save lives by providing clean water, reducing the impact of forest fires, or damping storm surges. For instance, the spidery roots of mangrove forests reduce the power of waves crashing against the coast during violent storms. An economist with India’s Institute of Economic Growth has estimated that mangrove forests prevented 20,000 deaths during the 1999 Orissa Cyclone in the Indian Ocean. But mangroves are one of the world’s most endangered ecosystems. They are being chopped down for firewood and building material and cleared for shrimp farms. In the last 50 years, their distribution has been reduced by 60%. Destroying mangroves rarely makes economic sense. One study in Mexico has shown that each acre of mangrove forest brings in $15,000 per year in seafood, more than 200 times the market value of their wood.

Of course, the economic value of the full gamut of ecosystem services is not always so easy to quantify.

How would you go about assigning cash value to a cooling sea breeze on a summer evening?

The challenge was taken up by teams of researchers led by Robert Costanza of the Australian National University in Canberra. In a study published in 2014, Costanza and his colleagues estimated that the total value of the goods and services provided by natural ecosystems in 2011 was $125 trillion. Their estimate was almost twice the total global annual gross product at the time. However, many of the goods and services provided by ecosystems, particularly extensive ones such as climate control by the world’s oceans, are simply irreplaceable.

Think About It

Are ethical and aesthetic values versus economic values mutually exclusive?

If some ecosystems, such as the Amazon rain forest or the boreal forests of Canada and Russia, provide ecosystem services that are global in significance, should the international community compensate the countries that sustain them?

What sorts of ecosystem services are simply irreplaceable and therefore invaluable?